Watercraft 1980

By Andy Ramus from his article ‘Watercraft, my part in its downfall’

Having kicked my heels for a couple of months after leaving Kingfisher yachts, I got an interview for an apprenticeship as a boat builder at Watercraft LTD on Harbour Way, Shoreham Beach. Dear old Pa had asked a couple of his friends, Paul Powter and Peter Kilner, who had sons already working there, to put in a word to get me the interview.

Barry Kilner and Ian Powter were apprentice ‘Marine engineer’, and ‘Ships Joiner, Yacht and Boat Builder’ respectively, and fellow beach boys like myself. Ians trade was the one I was hoping follow into, but I only had a leg up to the interview, and the minimum exam requirement demanded was four O level passes. Well, I’d taken eight and failed the lot, so I was pinning my hopes on the one year of experience I’d had at Kingfisher yachts swinging it for me. And a reasonable slice of luck!

On the big day, I was led up to the Production Managers office, Peter Weller, to be quizzed by him. I don’t recall being particularly nervous, and there are only a couple of things that are still stuck in my mind, looking out from his office window on to the shop floor of the boat fitters yard, other than being impressed by the scale of it, there was Ian Powter working on the foredeck of a P12 fast patrol craft, he saw me in there and a smile came up on his face, which kind of put me at ease. (Me and Ian both went to Cardinal Newman school in Hove, he was a couple of years above me. And everyday coming back from school would be this imaginary race between us to get home quickest. I used to be like a greyhound out of the traps when the home time bell rang, belting out of the gates down the Upper Drive on my way to Hove station, and then run like fury from Shoreham station to try and beat Ian home on Shoreham beach. The only trouble was, he cycled on his racer, and would always overtake me somewhere along Beach Green, smiling as he went past.) The other thing was that while being questioned by Mr Weller, when he came to ask me about my exam qualifications, I simply said that I’d left school over a year ago, and had been working at Kingfisher yachts next door. Thankfully it did the trick and he never returned to that question, but began asking me about my time there instead, and even though I had no idea whether I’d get the job or not, I at least knew the interview hadn’t gone badly.

When Mr Weller had done with me, I was then given a tour of the yard by the Boat Builders foreman, Bob Jackman, who introduced me to all the different workshops, and the extensive range of craft they were in the process of producing. Funnily enough I felt right at home immediately, but I was fortunate to know a few faces already, including a couple of the men that had been at Kingfisher yachts.

Well I got the apprenticeship, and on Monday 2nd June 1980, my induction into the world of Boat Building proper, began, earning the princely sum of 98 pence an hour.

The first person everyone had to deal with on their first day was George Carpenter, Watercrafts ‘gatekeeper’. He was a giant of a man, with hands like shovels, always wearing a long coat over his dungaree overalls, beneath which poked his boat sized boots, and a flat cap to keep his shiny bonce warm. George spoke with a slight west country lilt, as did many old time Shorehamers back then, but if he was raising his voice it could fill the yard and put the fear into whoever was present. His domain, when not assisting the sawmill foreman, Jack, was the clocking on area, just outside the saw mill, so first job would be to get me a clocking on card, and from that moment on, if you had any issues with your card, George was the man to sort it out for you. Many was the time I’d be belting in late to clock on, only to be elevated off the deck by his dirty great hands, “what are you in such an all fired hurry for Ramus?”, even though he knew only too well. If you clocked on more than three minutes later than the 7.30 start time, then you lost a quarter of an hour, and the possibility of being ticked off for bad time keeping. Later on I sussed, quite by accident, that the first person to clock on at the turn of the hour, actually got clocked for an hour earlier. Knowing this, if I was late I’d hang on and wait til 8a.m and clock on with 7a.m showing on the card, and even better on Saturdays I’d come in at 9 and get clocked on for 8 thus getting an extra hour at time and a half.

George had been a proper old school boat builder, often calling us soft, telling us apprentices how he used to cycle from Shoreham to Portsmouth everyday to get to work, leaving at four o clock in the mornings. But for all his gruff exterior, he had a bit of a soft spot for the apprentices, even if it didn’t always seem that way!. He took me under his wing for the first few days, sorting me out with an old wooden chest to keep tools in, (to be added later), sent me to the stores armed with a list of things needed for my new tool box. Next thing I knew I had a tool chest with shiny new brass binnacle rings, hasp, staple, and padlock, and then he steered me round to the riggers hut to get Ray Kennett to splice a rope handle on to the binnacle rings, and hey presto, one tidy looking tool carrier for yours truly. Ray, like many of the local born tradesmen at Watercraft, had learnt his trade at the coachworks at Southwick, under the arches of the long since gone road bridge where Stamco and Travis Perkins builders merchants now stand. A link back to the days when the railway was brought to Shoreham so that timber and other building materials could be transferred from the port along to the ever expanding town of Brighton where the Prince Regent, George was having his Royal Pavilion built.

The riggers hut was an eye opening experience to any new apprentices, its walls papered with either scantily clad or naked models, and cupboard drawers filled with Penthouse, Mayfair, or Playboy magazines. There was a wood burner in there that seemed to be perpetually going, so it was a popular stop off during the cold winter months. It also had its very own aroma, a concoction of rope wax, lifting strops, ash, oil, and stale cigarette smoke, I came to enjoy that smell. Little Johnny Goldsmith was the chief rigger, with his sidekicks Freddie Enright, and Ray, and occasionally John Liddle the company van driver. To my eyes they seemed like an independent state within the firm, no one appeared to hold sway over them, or over Little John at least, ( I should mention here that although John was referred to as Little John, I don’t think anyone would have dared do so in his presence, but he was even shorter than me). They were in charge of all boat movements, and that in turn meant John was in charge of all lifting, pulling, and moving, machinery. No engineers calculations involved, just a cursory eye over the job in hand, thumb and fore finger around the chin, maybe tip his captains hat back with a brief scratch of the head, and then out with whatever he deemed was necessary to get the object moved. This could be anything from a small 6 metre life boat, up to a 20 metre Naval training craft, and anything in between.

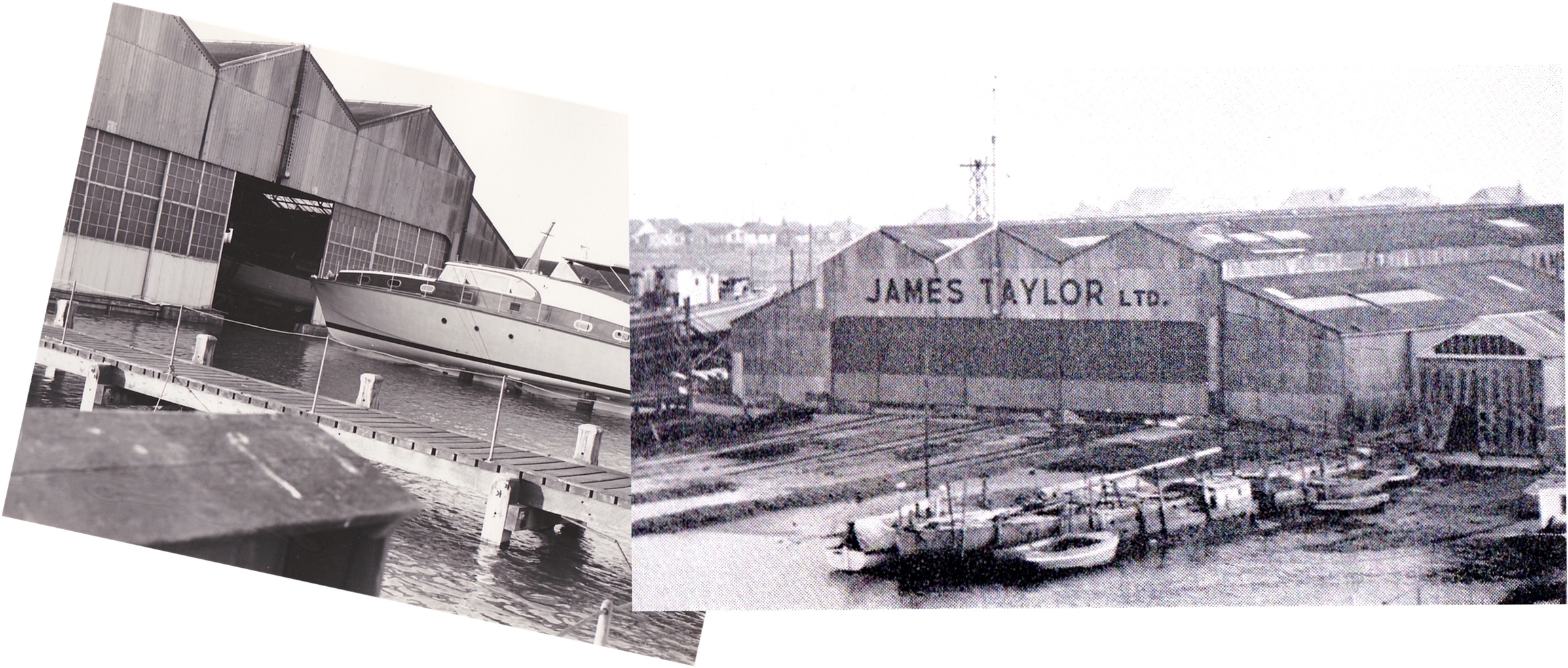

The frontage of Watercraft, on the bend of Harbour Way where Shingle road spurs off, was a middle section of blue painted office windows and entrance door, flanked on one side by huge metal sliding doors big enough to allow for boat movement in and out, and on the other side wooden slide by doors of the sawmill for timber deliveries. Adjacent to the sawmill doors were the twelve foot high wrought iron gates with the company name on them, through which boats would be brought from the Fibre Glass, or Steel shops, ready for fitting out in the main yard, or lorries would pass as they came to drop off or pick up deliveries. All in all it was a fairly imposing and impressive sight to behold, and a shame when you consider the horrendous eyesore which eventually took its place.

When you walked in through the wicket gate at the front entrance, (away from the outside world and into the time warp of the boat building industry), you were in the timber store for the saw mill, where in a bygone era they would have hauled in great logs by chain from the river, ready for quartering, planking, and milling. By the time I arrived it was just a timber store, filled with wood ready to be resized and planed up in the sawmill machine shop next door. Jacky Burt was the sawmill foreman, another born and bred Shoreham man, always with a big smile on his face, his hair long since gone a regal silver. Much like so many of the others, he had that mild West Country accent which I soon realised was very much a Shoreham accent, but one of yesteryear.

Jack was one of the first people you had to get to know properly as an apprentice boat builder, as he had to show you how to use the machine shop, which was a potentially very dangerous place. My favourite story he told me to get his message across, was the one of a lad that managed to chop his finger off at the overhand circular saw machine by waving his hand across while the blade was still at full speed, thus lopping a digit off. So, as Jack goes on to tell me, “I asked him how he did it, and the boy calmly waved his hand in identical manner, and lopped off another finger!”. I really don’t care whether it was true or not, the story stuck with me and was the first proper lesson learnt about having the utmost respect for tools which are sharp, fast, and basically bloody dangerous. I still have all my fingers, so good work Jack.

Once you’ve come through the wicket door entrance, and passed through the timber store and machine shop, you were now into the main yard, with the clocking on machine to your left, and the coffee machine on your right. Above the clocking on machine was the staircase to the loft floor, above the machine shop, where all the patterns and frames for new designs would be made up, my favourite time at Watercraft was my time spent there, but that would be a few years later. When I joined, the loft was old Toms area, where he would build bespoke wooden furniture to be fitted on the boats.

Tom had a fearsome reputation for being hard on the apprentices, but equally he was renowned for being someone that would teach you well, as long as you listened. He was also a diabetic, and on at least one occasion I saw him giving poor old Peter Weller a verbal lashing laced with some mighty fruity language while Peter was trying to calm him down and get him medicated during one of his funny turns, this one actually on the stairs and in full view of the shop floor. To this young apprentice it was amusing and disconcerting at the same time, you didn’t like to see someone being unwell, but it was like witnessing a tourettes outburst, and towards the Production Manager of all people.

Watercraft was one of Shorehams biggest employers back then, with over a hundred employees, of which about a dozen were apprentice boat builders, me being the newest recruit. In your first few months as an apprentice it’s all about taking stuff in without being a huge amount of use to anyone, so you get spun from one bloke to another for a while until eventually you’re left with someone for a bit of a run of work. The first job I was given to do on my own which sticks in my mind, was drilling limber holes in a P12 hull over in the Glass shop, not the most pleasant task to get. The Glass shop is where they lay up the hull and deck moulds, so it has to be kept at a constant temperature, very warm! It was the second largest yard after the main yard where the boats were fitted out, and the air inside was permanently tainted with the taste and smell of resin.

Bob Jackman had sent me off limber holing with these words, “it’ll be good experience for you”. Every boat once laid up with fibre glass, then has foam ribs, and longitudinals which run from front to back, glassed in for strength, and these need limber holes, which are drain holes that allow water to pass through the boat and find its way to the bilge. You’d have to try it to get the full benefit of quite how unpleasant it was, but drilling loads of two inch holes through cured fibre glass in hot house conditions aint my idea of fun, and you itch like a bastard afterwards. After that a piece of plastic hose had to be gelled into the drill holes, which while being messy, was nothing like as unpleasant. It’s funny how the nastier things in life tend to stick in your mind with such clarity.

Malcolm Brown, I think, was the first person I stayed working with for a continued period. He was a portly, proper old school chippy, in his dungaree overalls and polished up boots, quite abrupt in his manner, but not nasty or a bully. He also had a reputation for spending an inordinate amount of time in the crapper, a rep I soon realised was well earned. For some reason Malcolm had acquired the nickname of ‘Animal Brown’ among some of the lads, but I think it was more to do with the kind of jobs he was given rather than his standard of work. So when I came to be with him it was all boat cradles, or fender rubbers, neither of which required much in the way of finesse, but coughed up a decent bonus rate if you got stuck in. Boat cradles were the better and cleaner of the two jobs, as they were all wood, canvas, and sawdust; and from a training point of view, not too much harm to be done while picking up a good work ethic.

By the time I started my day release at Worthing College, I was pretty settled in and enjoying life at Watercraft. It was quite a family atmosphere there, especially if you were an apprentice, as even the most hardened grouches would take time out to teach you or give you advice if you asked for it. One of my favourite duties was as tea boy, which was shared around the younger apprentices. You’d get to leave to brew up in the canteen fifteen minutes before tea break, although you were making tea for between 20 or 30 blokes at a time, and in winter time toasting their sarnies too. Making tea has never been a chore to me, I still find it hard to understand when some of the younger lads on site grumble about making it, “would you rather be digging a hole?”, I ask, but it’s generally wasted on them. The staple of the British work force, learn to make it, learn to love it, should be mandatory!

The canteen was under the Production Managers office, and looked down on the main boat yard, which was about half the size of a football pitch, separated into slipways along which the boats would be manoeuvred through their varying stages of construction. Each of these sections had rolling chain hoists above, and work benches running between, which we kept our tool boxes under, unchanged for decades by the look of them. All the work benches had big gas heaters over them, but they didn’t do a great deal during the cold winters, merely warming your head if you were right underneath them, but I think the birds appreciated the extra heat so they weren’t completely wasted.

One of the earliest unsettling experiences anyone new would get, would be the Stores, which were halfway down on the left hand side of the main slipway. Den Pearson was the chief storeman, and if you didn’t have a proper signed chit for whatever you were asking for, you weren’t getting it, plus he growled. It wasn’t an uncommon sight to see a pair of legs being hauled in through the stores hatch by an irate Den as he dished out a verbal tirade. It was like you were stealing from his personal account, I couldn’t help laughing whenever he went into one, this I discovered would often disarm him because it was all a bit of an act really. I think it’s a stores thing, like there’s a manual that says you have to be nasty, and treat all fixtures and fittings as if they’re your own.

His sidekick, Eric was much more placid, and as a result if you didn’t have a chit, or wanted something out of the ordinary, you’d try and make sure you were dealt with by him, or Jim Edwards, who made up the stores trio. With Eric, if you wanted to shoot the breeze you’d have to talk about bikes, which I’ve never known or cared about really. You soon wise up though and realise you don’t have to know much, just enough to fire them up. Jim on the other hand was passionate about Arsenal and the Labour party, many’s the time we’d have him reaching out to get at us after chanting ‘Maggie Thatcher, Tottenham’ at him, all in good jest of course, but he was serious in his hatred of them both, coupled with a surprising ability to get more swear words in a sentence than you might have thought possible when on the subject.

With the summer fading in that first year, I was about to get acquainted with the harsh realities of a boat yard in the winter, more often than not it was colder inside than it was out, like a giant freezer. All around the yard were round bottomed metal fire buckets hanging from brackets, but sometimes the temperature dropped so much that they were solid ice, and if it snowed there were so many holes in the roof that we’d end up with inches of snow laying on the cab tops of the boats in the main yard, and the novelty of snowball fights inside was an opportunity not to be missed by us younguns.

Watercraft was full of colourful characters, as I’d imagine all boat building yards are really, I think it must be something to do with the industry, it just attracts that kind of people. You could build pretty much anything there, quite often you’d see bits of cars, motor bikes, push bikes, being worked on during lunch hours, furniture being repaired, or built from new, model ships taking shape day by day through the years, tools being made especially tailored to a certain job. One til 1.45 Monday to Thursday the workbenches were like a sprawl of little cottage industries as everyone took full advantage of the perfect conditions to get creative. This was an eye opener to me, and I soon came to enjoy walking around the yard checking on the progress of the various lunchtime projects, as did many others who didn’t have their own ‘homers’ to work on. It was like an in house craft exhibition. Pat Browns old style wooden planked, triple masted ship was one of the favourite ‘exhibits’ to stop and see. Every small detail attended to, each plank, spar, spreader, even the little brass cogs on the winches, all lovingly and meticulously turned out by hand over a period of years, creating this beautiful miniature ship from the past, and not forgetting the array of tools he’d had to manufacture to be able to work on such a minute scale. For others it might be part of an engine, either a practical repair, or a restoration job on some dated piece of machinery from back in the day when all things mechanical were Made In Britain. There was no shortage of motor bike enthusiasts at Watercraft, as you would be able to witness at the beginning and end of the work day as they all rumbled in and out, and what better place, and facilities, if you liked to tinker with your machinery.

You could bring in some old rusty piece of anything really, have it welded, shot blasted, spray painted, and taken away as if new. I remember Keith Saville bringing in his VW Beetle on a Saturday morning and marvelling at how easy it was to take apart, maintain, and put back together, all with nuts and bolts. It was at the bottom end of the main yard, where the marine engineers had all their machinery, lathes, pillar drills, heavy duty bench vices, and oil soaked work benches with metal swarf everywhere. Keith was a boat builder, a boat carpenter if you like, you’d only get unlimited access to the engineers facilities when they weren’t around, so Saturday on overtime was the perfect opportunity to take advantage. Homework seemed to be an accepted bonus of the job, just don’t be blatant about it, or more accurately, don’t get caught. But as Watercraft had a hierarchy that was promoted through the ranks, everyone up to Production Manager had started on the shop floor, and knew what the score was in this matter. Pretty much a blind eye situation.

Ross Smith the Engineers foreman, was a keen Speedway fan, he always came to work on his trials bike looking, as I remember, like he’d just stepped off the track, even with metal plates on the soles of his boots, which he told me once were for when going round the bends on the Speedway track so you didn’t wear your heels out. He’d been in the navy in his younger days, Merchant navy as I recall, and he was never short of some funny sea tales, most of which I ought not put into the public realms. His preparation for shore leave is one short story that still makes me smile, although I’d best not repeat, but it revolved around his expected entertainment once ashore. And his favourite line as I recall was, “so I says to this tart, I says, ay! Tart!, she says…. “fuck offfff””, all in a scouse accent, bearing in mind he’s a Scot. That saying still gets repeated by myself and other ex apprentices when we meet up, much like some people spitting out old Monty Python lines, and quite a few other little phrases which we instantly recognise for the person that used to say them. Keith Saville was probably the king of these as he had so many, “alright bonner” may have been his most used line as I remember. All of that just reminds me what a laugh we mostly had, even though it was work.

It was as well to be matey with Ross and his engineers, because you’d never know when you might need their help, for either work, or a homer. Barry Kilner I’d known since we were kids, through our parents, and being a few years older than me he was nearly qualified, so as a rule I generally went to him first for any help with drills, taps, dies, or lathe work. After a while though I got to know the other engineers, Tim ‘Surfers Ear’ Vary, the laid back and always amiable surf dude with a slight hearing problem caused by his years of catching waves. Every surfer has their own ‘near death experience story’, and Tim was no different, he once told me how while down in France he’d been caught by a massive set in the early hours of the morning, and kept under for so long that he wondered if he’d make it out alive or not, before eventually being spat back out and dragging himself up the beach to be greeted by this absolutely gorgeous, and completely naked woman walking along the sand, he said to me, “I thought for a second I’d actually died and gone to heaven”, but she carried on walking and Tim, happily is still in the land of the living.

There was Tony Wallis, a super keen cyclist, often riding his racing bike on some obscure routes back around the Sussex Downs for a marathon ride to work, a very quietly spoken man, and like Tim, mostly smiling. He and Tim were often teamed up as engine fitters on the boats, with Tony being the slightly more reserved of the two. Then there was Big Dave, the quiet Canadian, Ted Aylward, the beret wearing senior citizen of the fitters, and John ‘Muzzo’ Muston, who had a brother, Roger, over in the Glass shop. Apart from Dave, they were all local people, much like most of Watercraft then, which added to the kind of family atmosphere we mostly had there.

The boats going through the yard in that first year 1980/81 were, 40 foot cruise launches for the Sea Princess ocean liner, P12 fast patrol craft destined for the Middle East, P45 Pilot boats going to Port Said in the Suez, and a 14 metre steel M.T.V, (Maritime Training Vessel), for the Nigerian Ministry of Transport. That last one I remember only too well, I was fitting the fender rubbers on it with Dave Greenyer and Keith Saville. The fender rubber is like a D section snake of inch thick rubber that bolted all the way around the boat where the top deck meets the hull side, it has long lengths of quarter inch aluminium bar which we had to run inside it, then drill one inch bung holes through the rubber, and 10mm bolt holes through the aluminium.

When all that’s been done on the ground, you get it up on the staging around the boat and begin drilling through the hull and deck top overlap ready to fix the fender to the boat. To do this you have one person outside banging the bolts in, and one inside to get the nuts and washers on before tightening up with an air gun, or ‘whizzer’ as we called them, and extended stainless steel socket. As you’re doing the bolt up from the inside, communication is the key, so if you hear a tap on the side of the hull, you stop and take the whizzer and socket off while the person outside then gives the bolt head a bang with his club hammer and drift so you can then take up the slack after. Unfortunately for me, when Keith banged on the side of the hull, I pulled away the whizzer but the socket stayed in place, and as I went to grab it Keith had already engaged the club hammer and drift, shooting this long stainless steel socket like a bullet straight into my left eye and firing me halfway across the all metal interior of the MTV. I vaguely remember seeing Big Ted Clarke rushing down from the wheelhouse, then being carried out, and getting driven to hospital by Bob Phillips, he was part of the painters gang and one of the designated first aid crew. Later that evening I had a house call from a concerned Dave and Keith to see how I was, fortunately for me the socket had perfectly ringed my left eye, just leaving me with a juicy shiner, I even cleared their eye chart with the affected eye so no lasting harm done. It wasn’t anyone’s fault, but it was nice for them to make the effort to come around to make sure I was ok.

From September 1980 I was enrolled at Worthing Technical College on the ‘Ships Joinery, Yacht and Boat Building’ course as a day release student. All that time desperately wanting to get away from school, and here I was back in the education system, but this felt different and I actually looked forward to going. Ross White had joined as another boat building apprentice by now, and he could already drive so I got a lift in with him in his old white Ford Escort van, which he mainly had to get him and his surfboard to wherever the waves were pumping. It was at this point that I started getting an education in the world of surf, not that I took it up, just learnt the terminology and where the best surf spots were, quite often ending up at Littlehamptons West Beach during the college lunch hour when the surf was up, watching Ross take on waves the like of which I had no idea existed on our shores.

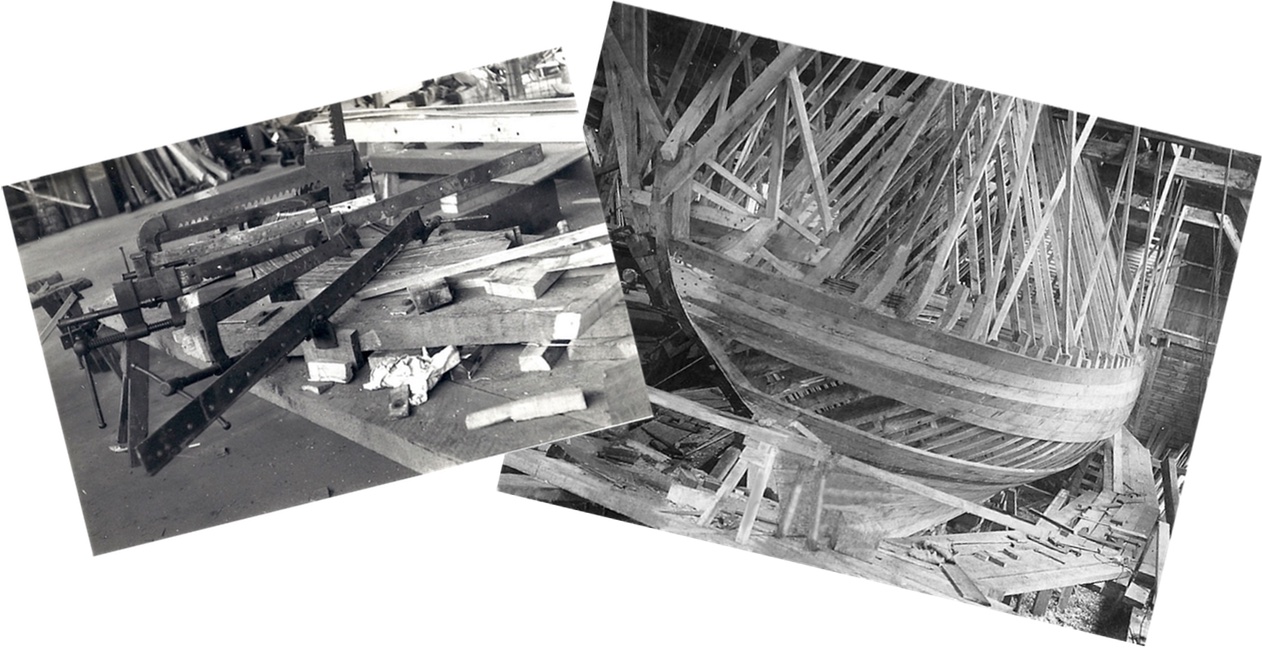

College was a world away from the work we were actually doing at Watercraft, where all the boats were of fibre glass, steel, or aluminium construction. My college education was like a bygone era of some romantic idyll of lovely hand crafted timber built boats, all wooden planked, double diagonal, parallel double skin, carvel, or clinker plank construction, with copper clench nailing, calico or canvas membranes, caulked seams, and a bewildering array of special tools to work with depending on which type of construction being used. Mr Smith, our tutor, took us down to the Elephant boatyard on the Hamble one time, as much I think to prove to us that people did actually still work in this way. It was lovely to see, in fact it felt like stepping back in time to a much slower paced life, but as soon as you’d return to work you’d be made quite aware that, while it is indeed an idyllic way to dream of making a living, the reality is that it’s a dying art.

Andy Ramus

© Andy Ramus 2004 All rights reserved.

For further details of Andys stories please visit his website http://wolf-e-boy.com