Survey of the old Vault in Church Street

Documentary Records.

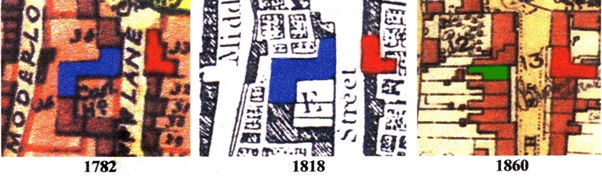

Described as a ‘Capital Messuage in 1738, the land within which the vaults are situated was owned by the Smith family and then, in 1782, passed to the Bridgers. However, the description of the property whilst mentioning ‘two tenements, malthouse, garden, stables, coach house and coachyard (which included the land and buildings southwards from the Manor House down to – but not including — the old Custom House and west [behind] the latter.) does not mention a vault or cellar at all.

In his book ‘The Story of Shoreham,’ Henry Cheal states of the site “….there is still existing a large tunnel-like vault built entirely of chalk blocks. It probably dates from the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century and was used for bonding purposes.” Michael Norman in his ‘Walkabout Guide to Shoreham’ offers that the old Custom House (from the appearance of a sketch of it in 1830) may possibly have been 16th century. This building then extended round a courtyard on three (south, west and north) sides but with an open side to the courtyard where Church Street is. Records indicate that much, if not all these buildings were used by the Customs for their Officers’ accommodation and for storage. It is also believed that some of the buildings south of the Customs House were originally built for storing confiscated goods and it is almost certain that the vault to the north was also utilised for the same purpose. More recent maps of the existing house compared with 18th century maps show that the northern side stood exactly above where the vault is and today’s main (western) external entrance would have opened into the inside of the building (if in fact there was access from inside then).

The earliest known written record of the vault as such is in 1831 when the Parish Poor Rates show them to be used by one I.H.Smith. By 1841 and 1851 if not before, the Shoreham property developer G.H.Hooper was the owner and West, Hall and Smith (probably wine and spirit merchants) rented the vaults for storing wine. Shortly after the Customs moved to their new premises in the High Street (also built by Hooper) he then demolished the old Custom House in Church Street and built in its stead the terraced houses we see today. It was at this time the vault became part of the new house above it and, as far as we know, ceased to be used for commercially as there is no further mention of it.

Physical Survey

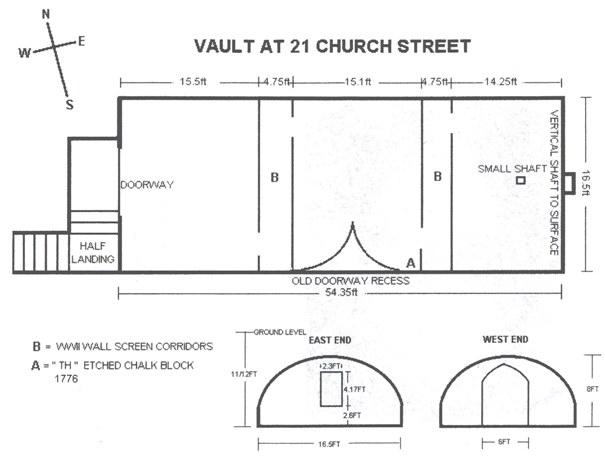

At ground level, evidence of the vault can still be seen from two stones in the front garden of No.21 which cover a brick lined vertical, rectangular shaft down which coal was once dropped into the front part of the vault for storage until required for use in the 1850’s house above – there is no evidence of other use to indicate physical access at this point.

At the rear of the house well into the back garden there is an external doorway to the main entrance to the vault and, bearing in mind the depth of the existing house from back to front and more, the vault’s entire length can already be gauged as considerable!

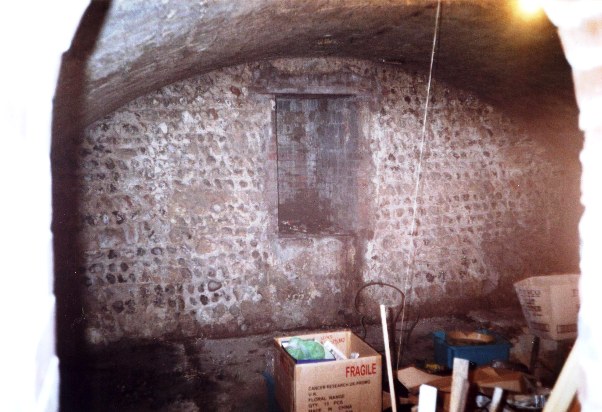

The steps down head eastwards back towards the house and are wide and roomy — unlike other vault and cellar steps elsewhere in the town and indicative of intended access for large and bulky items. There is plenty of headroom and no crouching is necessary as the steps progress down halfway to a half landing before turning left at right angles the remainder of the way. The bricks making up the steps and the wall on the northern side of the steps look to be fairly recent and may be the result of strengthening and renovation during the last century. The wall on the southern side however is flint and mortar and continues down to the vault floor — could this be the last vestiges of the original pre- 1850’s building? Upon reaching the bottom landing immediately on the right is a large brick edged, arched doorway that was originally 6 feet wide but now slightly narrowed by a strengthening wall and probably would once have sported an impressive stout oak door or doors with massive iron bolts and locks to secure the contents from unwanted attention — as a commercial wine storage and perhaps also during use by the Customs.

One step down from the archway the floor level is 11 to 12 feet beneath the ground and the large dimensions of the vault can now be appreciated. At sixteen and a half feet wide the floor’s width almost matches the 17 feet width of the house above. This floor (now a cement covering) is bounded on each side by low flint and brick walls that continue up with chalk blocks in an impressive vault-curve, the highest point of which are 8 feet above the floor. Sadly, two sets of double screen brick walls built across the width of the vault during WWII and intended to provide extra strength for use as an air raid shelter (but nevertheless part of it’s history) now prevent an unimpeded view down its entire 54 foot length — a sight that must once have been very impressive.

.

The remaining low walls all along the sides of the vault appear to have something of a pattern in their construction in that every 4 or 5 feet or so there is a brick arch that may have been strengthening or perhaps even have been above storage recesses in the wall. Due to their age, wear and over covering of their edges by enthusiastic mortaring it is difficult to be precise about the dimensions of the bricks used. However, these seem to range from 8.5 to 9 inches long, 3.5 to 4 inches wide and 2.25 to 2.50 inches deep — allowing for regional variations this places the age of the bricks as 18th century and probably nearer the mid 1700’s. Nevertheless, this is the age of the bricks only, not necessarily the main chalk block construction and may only indicate a reconstruction stage in the building’s history.

The chalk blocks themselves are something else altogether and, as an age old construction method going back centuries it is virtually timeless. The vaulted chalk roof in St.Mary’s church is one example which may indicate that the Church Street vault could possibly be older 18th century. Chalk is readily available locally, is soft and easy to carve and shape but equally it is not suitable for outside use where it would soon be eroded by the weather. Apart from one or two blocks that have been part ‘powdered’ by chemical reaction, most appear to have become quite hard during their time as part of the vault which again may point to antiquity. None are precise in dimension but most are around 14 inches long by 6-7 inches deep, some are smaller and others are up to 22 inches long. From those specially shaped returned blocks for the old entrance it appears they were a more consistent 6 -7 inches wide.

A little over fourteen feet into the vault is the first WWII wall screen which, due to the lack of weathering of inside conditions, looks almost new. These are not particularly important but warrant some mention. All of these extend from wall to wall and up to the ceiling. These each consist of a set of two walls with a narrow 57-inch passage between each. The first of these of walls has a man sized curved topped doorway on the south side and a low, square access gap on the north side, the latter presumably for passing through small pieces of equipment. On entering the south doorway the first passage turns left to reach the north wall with the access gap on the left and another man size doorway on the right into the second vault area. After that area the process is then repeated with the second set of wall screens with the door on the southern side, northwards through the passage to the last access gap on the left and doorway on the right into the final part of the vault on the right.

Returning to the second vault area the wall and roof pattern is repeated apart from an unusual recess in the roof against the southern wall. The chalk roof arch of this recess provides an almost church-like alcove to create a taller vertical wall measuring 7.5feet high at the apex and six feet wide as compared with the remaining lower 3 foot (approx.) wall that runs along the length of both sides of the vault.

There is no matching cut-out on the opposite wall, nor elsewhere in the vault and it seems unlikely that such a relatively small area (compared with the total size of the vault) would be especially cut out, for example, to be able to store a tall object up hard against the wall. As we have seen, todays’ external (western) entrance would have been inside the older pre 1850s building and upon inspection the recess is not a cut-out as such but architecturally sculpted with specially shaped chalk blocks that faithfully follow the curve of the roof and the returns to the wall where a door may once have been. At first sight the wall here is filled with random chalk blocks, bricks, flints but mostly mortar and in appearance seems almost as old as the remaining original walls themselves. However, the blocking up of the old entrance even as recently as 150 years ago when the houses now on the site were first built, would still have involved the builders using any old unwanted and original material lying about inside and outside of the building.

Everything points to an original entrance that exited out southwards, probably up steps to the courtyard area and at the very least provides an architectural feature that so far as is known cannot be seen anywhere else in town.

Just a few feet east of the old doorway is an inscription in one of the chalk blocks on the same south wall/ceiling:- T H 1776. If genuine, this ties in nicely with the 18th century brickwork and although the initials do not coincide with any of the recorded owners that we know of they could possibly be indicate the name of Thomas Hanington as the Hanington and Roberts families jointly owned and developed a number of properties in the town at this time. If it relates to the chalk work then was it the date of the construction of the vault or repair work?

The final area brings us to the front/eastern end of the building where the vertical shaft to the surface is set into the wall. As previously mentioned the current owners confirm that this was once used to drop the house heating coal down for storage. Three feet inwards (west) of this shaft and the end wall there is another, much smaller rectangular shaft 6 x 4 inches in the centre of the roof to ground level above – perhaps to provide a source of air when the doors were closed and the shaft at the eastern end did not exist.

How old was the Vault?

The physical and documentary clues are not straightforward. If the building above the vault was as old as 16th century then it seems unlikely that anyone would have gone to the trouble of excavating the vault from the side of and under an existing building — the expense would have been considerable and there would have been a distinct danger of weakening and collapsing the building above during excavations. Assuming the vault was built first and the building above was 16/17th century then it follows the former must date from the same time if not before.

The inscription ‘TH 1776’ on one of the chalk bricks is intriguing and if it does record the year when the vault was dug out then the building above the cellar is more likely to have been built after 1776 unless it was inscribed when the cellar was renovated. Perhaps the southern (Customs House) part of the overall building was 16th century and the northern part above the vault more recent.

At the beginning of these notes we saw that Shoreham’s foremost historian Henry Cheal reckoned the vault was probably late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. He describes it as being ‘tunnel-like’ built of chalk blocks so must have seen the place for himself and having a known passion for accuracy and detail the 1776 inscription would have been too obvious for him to miss. However, until such time as expert opinion can be obtained this is probably about as close as we can get.

Roger Bateman

Shoreham

November 2002

How interesting. Thank you.