A unique record of Shoreham’s war as seen through the eyes of the people that lived through it. Probably the most complete record to date of wartime edited from the reminiscences of many contributors to the shorehambysea.com web site history forums and others, in particular Gerald White (whose article ‘Shoreham in World War 2 – A Diary of Events’ has provided much general information for the background of this record) and John Lyne who were both near neighbours in Connaught Avenue. Special acknowledgment is also due to Peggy Bailey a Shoreham Beach resident, Cynthia Bacon once of Swiss Gardens for her memories and photos and to Brian Bazen who lived in Eastern Avenue whose reminiscences in full can be seen on ‘Britain at War’ at Telegraph.co.uk

Shoreham Prepares for War

By late August of 1939 few doubted that war was likely as Peggy Bailey recalls – “Talk of war was rife then and people started hoarding, filling their larders with food. We were issued with gas masks and sandbags were provided if you wanted them. On September 3rd 1939 war was declared and I was with friends that day listening to Mr. Chamberlain on the wireless telling us the frightening news. I rushed home where my mother made us put our gas masks on as the siren had just sounded and she was sure we would all be gassed. Being children we had no real fear of the consequences of war and thought it all rather funny making rude raspberry noises by blowing, expelling the air out of the sides of the masks.”

Germany’s invasion of Poland and Britain’s subsequent declaration of war also resulted in one of the first incidents in the conflict to be witnessed in Shoreham when three Polish airmen who had escaped from their homeland flew across Europe and landed at Shoreham airport. De Havilland Dragon Rapides of KLM and Sabena also landed at the airport with refugees – the Sabena airliners having been previously transferred from Croydon Airport at the outbreak of war.

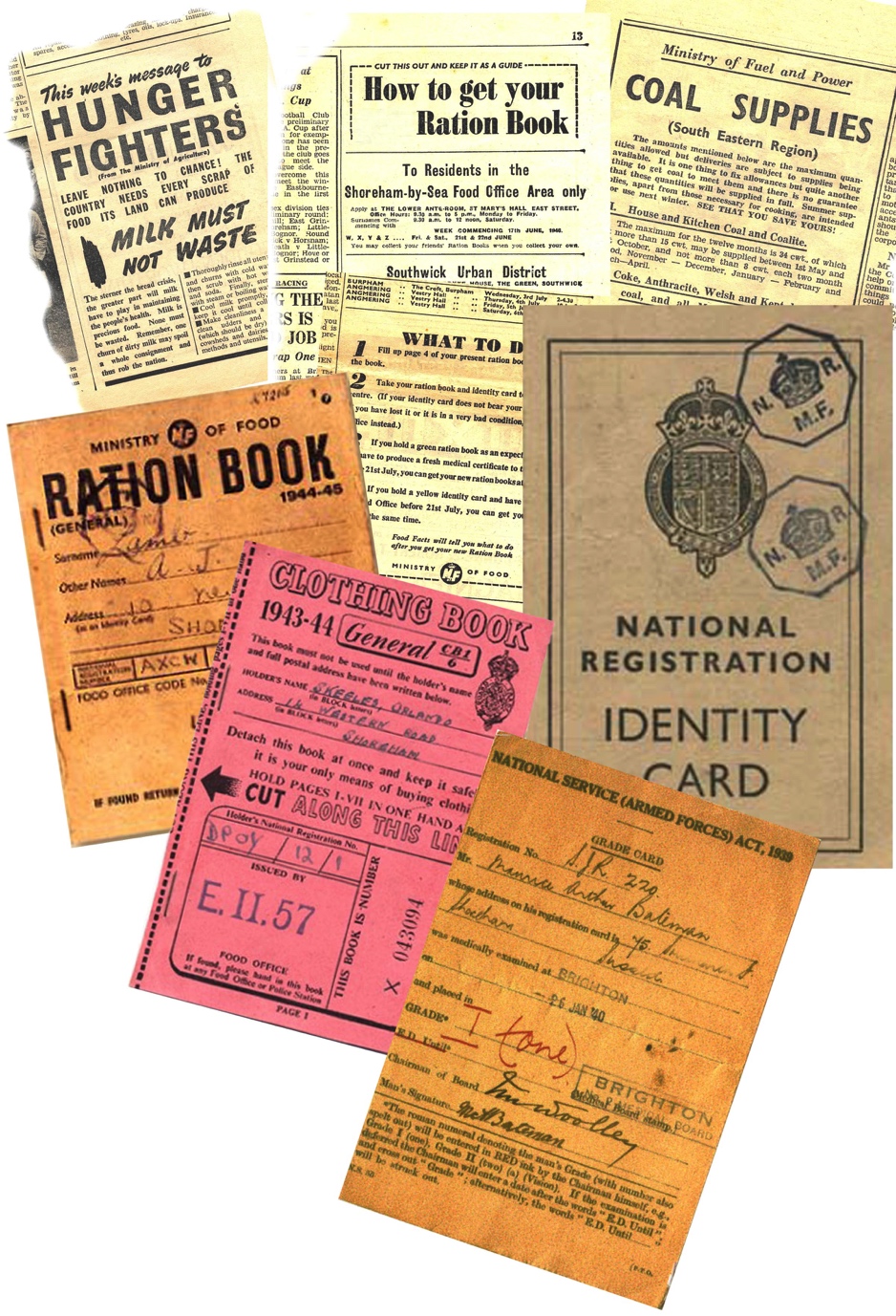

Shoreham wartime rationing announcements, ration books, identity cards and enlistment medical grade card from Queens Road in Brighton

Despite popular belief the internment of aliens in the UK was not wholesale and only about 600 throughout the country were considered a high security risk enough to be interred. Perhaps that also included this one time Beach resident: – “We went to the Church of the Good Shepherd on Sundays and walking to it along Beach Road we would pass one house that often had its’ windows open from which we could hear Hitler’s speeches ranting out from a wireless – the lady that lived there was German and she was interned when war was declared.” Peggy Bailey

In Shoreham the Territorial Army gunners 113th Regiment of Field Artillery based in Worthing set up a field Headquarters at Buckingham Park. The guns, 25 pounders, had only that summer been used on training at the annual summer camp at the Okehampton ranges. The brand new guns were dug in at Buckingham Park and were ranged onto the airport

and Shoreham Beach where it was thought the invasion landings might occur. The Shoreham battery was taking its first positive action in what was to be a long war. In the days following the outbreak the National Service Act was introduced and call up was announced for all men between the ages of 18 and 40. Local men were required to attend for medicals at Oddfellows Hall in Queens Road Brighton.

A new defence force called the Local Defence Volunteers was formed and volunteers registered their names at Tarmount police station. In the early days sceptics viewed the organisation as something of a joke and that the initials stood for Look, Duck and Vanish. By 1940 it was renamed as the Home Guard with battalions within counties and further reorganisation in 1943 resulted in Shoreham becoming the 9th Sussex (Shoreham) Battalion Home Guard. Many volunteers were too young for regular service and others were veterans of the Boer and the Great War which had only ended 22 years before. Sixty year old William White, a Corporal worked as a storeman in the local Home Guard situated in the ex. serviceman’s club in Connaught Avenue which later became the grammar school playing field and gymnasium.

Adults were required to register themselves and be issued with identity cards that were to be shown on demand to the police, and any member of the armed forces on duty. Ration cards were issued within a month of the outbreak of war and Shoreham’s resident population had to register with one particular butcher or another from a wide choice in the town that included Alfred Snelling, Ted Harmsworth, Jack Shepherd and Evans & Upton. As the war progressed the portions of meat available became smaller and smaller although offal was never rationed.

Street lighting was turned off, the black-out introduced, cars had hoods with slits fitted over their headlights and whenever you stepped outside your house it was all very dark unless there was a moon. Road signs were taken down to confuse any invading armies and white lines were painted on roadways, black and white kerb stones fitted onto pavements (they can still be seen in Victoria Road between the school and the old Hebe pub) bent sections of railway lines were fitted to prevent access on to strategic roads (there is one surviving rail at the west end of the Toll Bridge). Torch sales increased but batteries were not efficient or long lasting with the result that more candles were sold as winter set in. Double summer time was introduced which forwarded the clock by two hours in summer to help make the most of daylight to assist the farming and other outdoor work. The Land Army was formed to replace farm workers who had been called up and young women were to learn the farming skills instead. Ruth Bowley of Shoreham, for example, had to milk a herd of 50 cows daily before breakfast as part of her daily work.

The Evacuees Arrive

In the early part of the war life continued fairly much as usual except that air raid shelter drills were practised at school and the school day for local children was reduced to half a day – locals in the mornings and evacuees in the afternoons. Many of the bungalows on the Beach were, even in peace-time, empty outside of the summer months and even more so in wartime. Then evacuees started arriving in the town: – “They all came in by train and Mr. Perkins, the garage owner, opened both of his garage’s doors so that the children could walk straight from the station through to Ham Road and the Children’s Home which stood where Somerfields is now. From there the children were literally selected by people in the town who were required by wartime legislation to provide homes for them. We had an evacuee girl called Rita, a very quiet girl of nine – her brother was billeted across the road with our friends, a very streetwise Londoner – their father, a London taxi driver, came to visit and was so pleased to see she was happy here with us that he gave my sister and I half a crown, a lot of pocket money then.” Peggy Bailey

Peggy Bailey and Rita the evacuee from London in the garden of their bungalow on the Beach (photo Peggy Bailey)

The police station in Tarmount Lane was served by a sergeant and a small number of constables together with a number of war reserve special constables. On Truleigh

Hill the Royal Air Force had an installation called RDF (Radio Direction Finding) where only the aerials were visible as the operators were deep under the hillside. The radar unit was part of a ring of coastal early warning radar stations codenamed Chain Home – Truleigh Hill was situated between its sister units at Poling to the west and Beachy Head to the east.

Invasion Fears and Defence Preparations

The war in France was not going well and the mood in Shoreham can best be measured by Peggy Bailey’s recollection:-“When Dunkirk fell we were all rather frightened and lived with our suitcases ready packed after being warned that we might have to leave our homes at short notice. Unbeknown to us Mother owned a gun at this time and if the Germans had invaded was prepared to shoot us – something we weren’t aware of until many years later.” Access to and from the Beach via the footbridge was only permitted at certain times. There used to be a curfew and residents had to be home by 9 o’clock when the footbridge was closed, the middle section drawn back to prevent access and a guard posted at Kings Drive at the road entrance to the Beach.

The threat of invasion decided the War Office on clearing the beach to enable a clearer view of invading troops and therefore easier defence by our soldiers and guns on the higher ground in and behind the town. In August 1940 residents on the Beach were given 48 hours notice to move out as the War Office feared that in the event of invasion the Germans could use the area to gain access to the town and the country beyond by using the bungalows as cover. “Mother managed to rent accommodation on the mainland from someone who worked at ‘Ricardo’s’, there were plenty of houses that were empty then as people were moving inland away from the threatened areas. The army themselves actually moved us. Items of amusement were restricted to one per household so my sister and I chose our wind-up gramophone although Mother wanted her piano as well. As luck would have it the piano had to be moved as it was in the way of the necessary furniture but in being moved got stuck at the front door. A sergeant was called over and said we already had our one permitted item (the gramophone) but the soldier moving us pointed out that it had to be got out of the bungalow in order to gain access to the rest of the furniture and couldn’t be put back in – as a result Mother got her piano after all. Peggy Bailey

Most of the bungalows and old railway carriages that were built into them were blown up by the Army from West Beach to Ferry Road and all along the foreshore right up to the Old Fort. Peggy recalls “The detonations could be heard all over the town and even when this was finished they laid mines along the beach which would occasionally explode during high tides and storms and could be heard above the noise of the wind.”

The mines were planned to be planted at the time Sam Maple worked for the Sea Defence Commissioners. Sam warned of the problems that could result due to the tide movements there but it went ahead nevertheless. Apart from the detonations during rough seas that resulted there was another worrying incident when a dog approached Sam on the beach with one of the mines it had dug up.

A desolate Shoreham Beach with the Church of the Good Shepherd in the distance after the bungalows were demolished (photo West Sussex Archives)

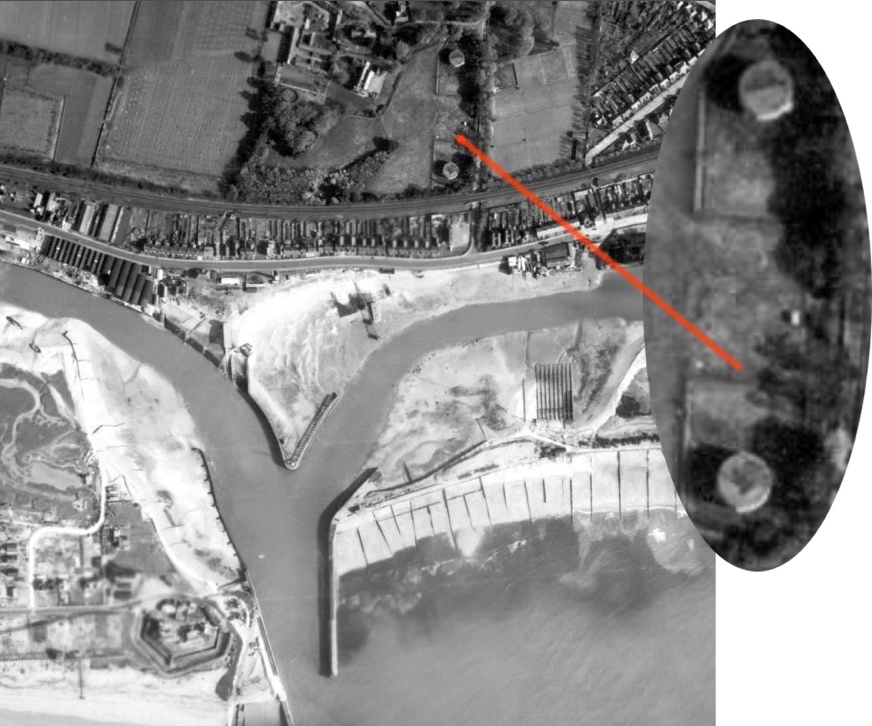

Large containers of a mixture of petrol and oil were installed in the grounds of Caius School, now Shoreham College, at Kingston. Pipelines ran underground to more fuel tanks at the harbour mouth and canal ready to be pumped out and set on fire by the Navy in the event of invasion. The residents of Bungalow Town had to evacuate home in a hurry and leave most of their furniture behind and looting was known to have occurred despite the presence of the troops.

Oil tanks at Caius School by the harbour mouth (1940 photo Sussex Air Photo Catalogue)

A line of defensive obstructions and concrete blocks 6’x6’x6′ were placed all along the open stretches of coastline. Beaches were mined, barbed wire entanglements set up and known gun emplacements were made along the river bank by the airfield, the grammar school playing fields (now Greenacres) and two large Bofors anti aircraft guns in the Nicolson Drive end of the Ham Field allotments. When one of these guns was fired for the first time Mrs. Robina Page, a member of the gun team, fell completely off the gun platform.

Gas attacks were a real fear and gas masks were issued to everyone young and old. At school children were shown how to wear the gas mask and ensure that it was carried at all times. Practice rehearsals in the event of bombing were carried out and each pupil was allocated a place in an air raid shelter so when the class was evacuated everyone knew where to go. In Victoria Road school the shelters were situated in the Meads meadow.

John Lyne recalls “I collected my gas mask from the St Wilfrids building, this to my great pride was a ‘grown ups’ one, not the Mickey Mouse type given to young children and walked back through blacked out streets past houses with taped up windows and small piles of sandbags. The gas masks were to be taken to school (Victoria Road Infants) in the morning and hung up with your coat. If there was an air raid warning sounded (an oscillating wail) you picked up the gas mask and filed into the shelters built in the Meads until the ‘all clear’ sounded.”

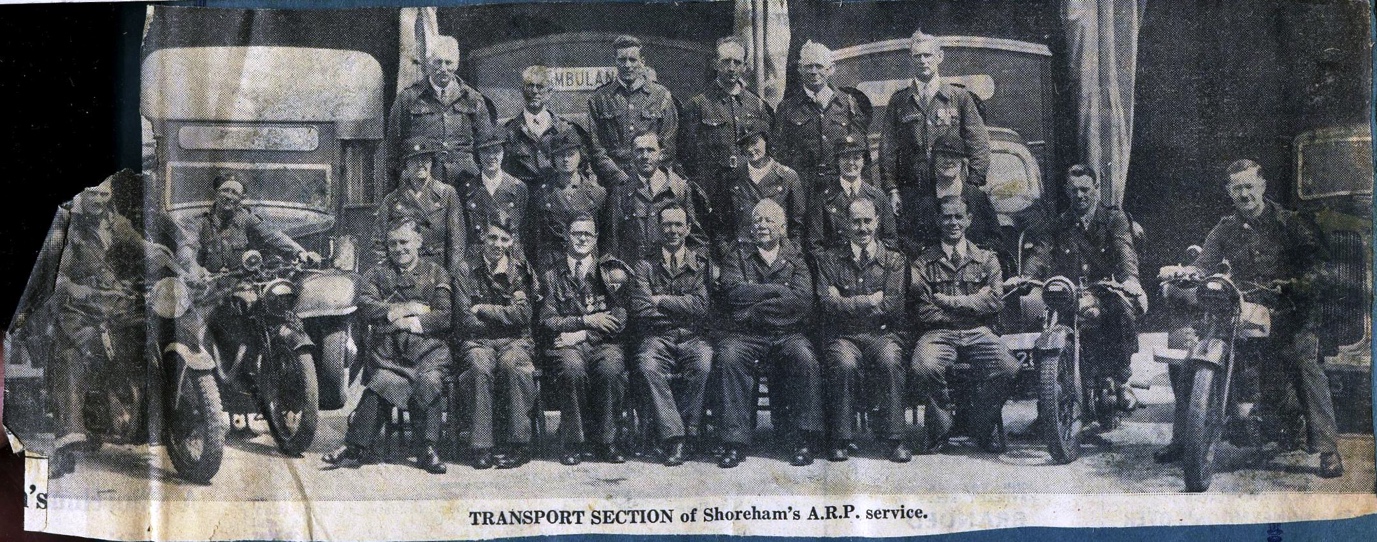

The members of the ARP (Air Raid Precautions) patrolled the street at night and warned residents of any lights which were showing with the call “put that light out.” Each member carried a whistle which they were to blow when warning of a gas attack or unexploded bomb in the vicinity. One of the ARP members was John Clements, an affable and well known figure in the town who, in between duties bought fish from his cousins the Lakers and Pages and sold it on from his cart at his pitch in the High Street outside Marlipins Museum. The ARP was based with the Fire Brigade at their HQ in the old school in Ham Road. This combined team were trained to deal with bombings, fires and provide first aid. Important buildings like the post office and the town hall were sandbagged to reduce damage from bomb blasts.

In the Grammar School playground shelters were dug partly underground about five or six feet with a reinforced top and earth pile along the sides. At some time during the war the Fire Brigade was also located here, presumably after moving from Ham Road – the classrooms were on the north side of the school whilst the Brigade occupied the south side after converting some of the classrooms for garaging the fire engines.

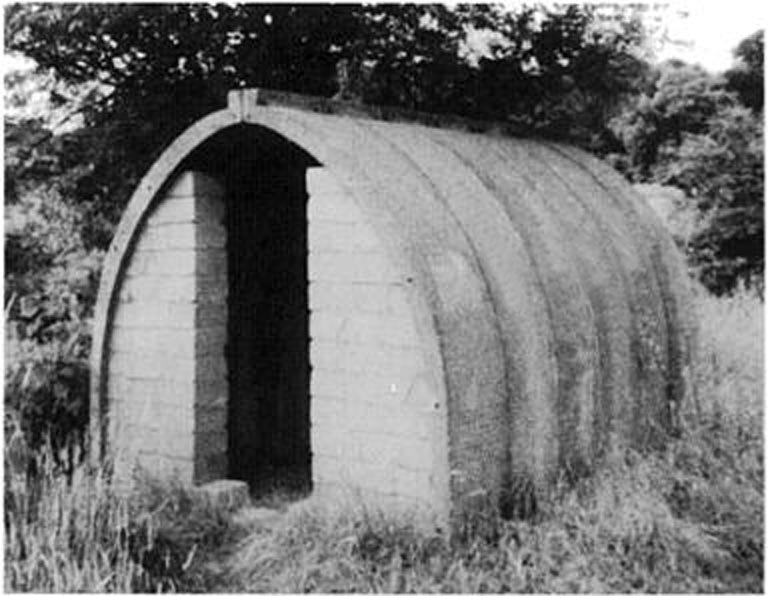

Air raid shelters were built on the Ham in Ham Road, another was in Connaught Avenue on the green and behind Victoria Road School as already mentioned as well as many others strategically placed around town. Other forms of domestic shelters were outdoor Anderson shelters provided on a self install basis for use in gardens. Morrison shelters were for indoor use and took the form of a large steel table with caged sides where members of the family could sleep – all these provided some protection except in the case of a direct hit:-

“Our home air raid precautions consisted of taped windows, black-out curtains and a strong timber framework in the living room supporting the ceiling, our neighbours had a large steel table of sufficient size to accommodate the whole family and we shared an Anderson shelter that my Grandfather helped to construct in their back garden, there was also a large communal shelter and water tank built at the northern end of the green in Connaught Avenue. We used the Anderson shelter when there were air raids, mostly aimed at the airport but mostly the warning sirens were not precursors of a raid. Even at our young ages we could tell German bombers from ours by the distinctive sound of the engines and from what I remember the Germans had a low ‘pulsing’ note.” John Lyne

Bombing Raids

Shoreham Herald of 6th October 1944

A surprising total of 37 raids were carried out on Shoreham and Southwick by enemy aircraft during the war. These involved 143 high explosive bombs, 5 oil bombs and in excess of 2,000 incendiaries causing the deaths of 17 people and injuring 108 others. Eight of these fatalities were Shoreham residents but whilst separate figures for the raids on Shoreham only are not given the following incidents account for most of them.

It is thought that the first bomb believed to be dropped on Shoreham exploded near searchlight batteries on the Downs at the back of the town. It missed them and just made a hole in the ground but the area was subsequently much visited by local children picking up shrapnel from the crater to add to their collections of spent bullet cases and thin metal strips dropped to confuse radar known as “chaff.”

On the 13th August 1940 four residents in the Lower Brighton Road were injured when eight bombs were dropped. Another raid involved newly married Emily Hudson (nee Clements) who had moved with her husband to New Barn Road opposite Southlands Hospital where she worked near the now forgotten Burfoots Golf Clubhouse, a building of predominantly timber construction. There were only six or so bungalows there then which were virtually in the countryside. Ack-Ack guns were sited only just down the road at Burfoots’ Gardens near the Green Jacket pub and were a frightening thunder of noise when enemy aircraft were about. As it happened, Emily’s home was one of the few in Shoreham to suffer a hit from German bombs, in her case an incendiary bomb which brought her ceiling down but luckily burned itself out without destroying the bungalow.

A sentry and friend at the entrance to Golden Sands at Lancing (photo Winton Collection)

It was this same raid that Richard (Dick) Steers remembers. A young man at this time living at Greenways Crescent, Dick first worked for Braybons and was particularly proud of the roofs that he helped construct on the parade of shops that were being built opposite the hospital just above his home. As he left his house he was met with the sight of a line of unexploded incendiary bombs on the green in front of him, sticking out of the earth with their fins showing like a row of vegetables on an allotment. This was a continuation of the stick of bombs that had hit Emily Hudson’s home and, to Dick’s dismay, had also straddled the shops to burn and demolish part of the roof he had built.

On the 13th August 1940 seven high explosives and one oil bomb were dropped on the Lower Brighton Road when four people were injured. Fifteen days later eight bombs were dropped northwards from Middle Road where residents actually saw three of the bombs falling from one German bomber which demolished a few houses. Fortunately no one was killed and only one person was hurt. An incredible 53 incendiary bombs were reported to have been dropped on the 14th September that same year but this probably included neighbouring Southwick.

During the afternoon of 26th September bombs fell near the railway viaduct (probably the target) when seven people were trapped in the demolished houses which were part of Buckingham Cottages in Buckingham Street between the viaduct and the Swiss Cottage Inn. Cynthia Bacon recalls “I remember one of the women who lived in the Cottages saying she was pinned under a slab of concrete after the raid and could hear the rescuers walking over the concrete but she wasn’t found until a while later. We lived at 6 Swiss Gardens which was close to where the bomb fell but only suffered broken windows probably because the trees between us and the bomb saved us from further damage.”

One of the other bombs dropped by the same aircraft during the pass fell between the Steyning line bridge and the viaduct. This was on the west side of the Old Shoreham Road opposite Viaduct Cottages where it exploded, narrowly missing the Imperial Laundry building but smashed most of its glass roof where eight of the girl workers were cut by the flying glass. “They bombed the laundry and railway bridge completely taking out the corner where my Mum’s steam press was situated. She was in the toilets having a smoke at the time! The railway bridge suffered as well, one of the pylons being badly damaged and you can still see the strengthening bands that were fitted as a repair.”- Richard. A further bomb did not explode but lodged into the river bank under the railway bridge and had to be defused and removed.

Top: Daily Herald newspaper photo showing the damaged houses at Buckingham Cottages.

Below: Evening Standard photo of the damaged glass roof of the Imperial Laundry and the water filled bomb crater in front of it.

(from the collection of Cynthia Bacon)

One night a local member of the Home Guard who also worked at the Beeding cement works witnessed the bombing of the railway line adjacent to the works. The line had been damaged and, realising that a goods train was due, ran waving a lamp for it to stop thereby preventing a disaster.

In the Grammar school playing fields (now Greenacres) there were trenches, a large searchlight, an anti aircraft gun and heavy machine gun emplacements as well as a barrage balloon which was floated from time to time. “I clearly remember one evening there was a raid on the harbour and power station the searchlight went on and the machine guns opened up with tracer bullets and we watched it from our shelter entrance in the back garden – the tracers seemed to weave and float into the sky (very pretty!). I also saw a plane diving vertically, caught in one of the searchlights to the east of us and thought that it was a German plane that had been shot down but found out a few years later that it must have been a dive bomber.” – John Lyne (possibly the raid on the power station during the night of 27th August 1942 when 37 year old Sidney Martin was badly injured and died later at Southlands hospital).

The worst death toll occurred on 21st October 1940 when a delayed action fused bomb landed by the Shoreham Shipping Company (south of the Brighton Road opposite today’s B & Q store) killing five persons including a 17 year old Home Guard George Earthey, Arthur Laker a fire fighter and John Hoad all from Shoreham. Three others were killed and six injured in another attack on November 9th making eight Shoreham fatalities in total for the whole of the war.

The biggest raid of all was an attack on the railway bridge at Kingston Lane on the 8th October 1940 when 24 high explosive bombs were dropped and although they missed their mark one hit the Church of St Michael at Southwick and resident Mrs Alice Ford aged 35 of the Tile Cottage, Rectory Gardens was killed and elsewhere in the Kingston Lane area six others were injured. On 17/05/1941, the SS ‘ Ala’ was bombed whilst just outside the harbour killing one person on board. There were other raids on the harbour in April, May and June of 1942 but these are thought to have been in the Southwick area and during the course of the war generally Southwick town also received its own fatalities.

The newer utilitarian houses on the west side of Queens Place at the railway end are said to have been built to replace ones hit by bombs and evidence of other wartime damage can be seen from the distinct bullet/shrapnel marks around the railway bridge in Southdown Road, still very obvious on the pavement on the eastern side under the bridge.

Shoreham airport received its fair share of attention from enemy raids and these are already well described in the book ‘Shoreham Airport Sussex.’ During 1940/1941 marginal damage was caused in five raids but on the night of the 8th September 1941 the fourth, heavier attack destroyed the main hangars and put the airfield out of action. The last raid of 1941 took place on the 19th December 1941 during which ACW Phyllis Hicks of the WAAF, aged 20, was killed. The airport’s biggest raid of all occurred on 13th February 1943 when the control tower was hit and other building set on fire but otherwise no significant damage was incurred.

Machine Gunning

Death and injury from bombing is bad enough but the indiscriminate machine gunning of civilian targets seems somehow more disturbing. The Kingston Lane casualties of 1940 included injury from bullet wounds – this was not an isolated example and there were a number of other instances of this. “Another of these raids concerned the old Adur Rec. which was on the north side of the road to Lancing between the Norfolk Bridge and the flood arches. Enemy aircraft were flying low and trying to shoot up goodness knows what. On this particular day my mother was pushing me in my pram into town when she heard the plane arriving. It started spraying the road with bullets and she pushed me – still in the pram – and followed me, and we both slid down the steep slope onto the ‘rec’. It was quite deep in those days.”- ex.Shoreham resident

Connaught Avenue is remembered as receiving attention from Luftwaffe machine guns possibly because it looked like a runway with an apron from the air. Brian Bazen also recalls seeing bullets flying up from the pavements when his sister, Pamela, was machine gunned by a German plane which strafed Eastern Avenue. A man protected her with his body and fortunately both were unscathed. In contrast there were also reports of a “gentleman” German bomber pilot who flew over every other night, dropped his bombs in the sea and went home.

The war meant considerable extra work for some, particularly those in the Town Hall as Gerry White relates, “One of the busiest men in town during the war was the chief Town Clerk Mr Thick. For many years notices posted by the UDC had the signature ‘…….Thick, Chief clerk’ which many of us thought amusing.”

At home the wives and mothers also helped with the war effort “My Mother billeted WAAF’s and the occasional airmen as we had a spare room. The ‘guests’ would inscribe the ceiling support timbers with their names and addresses, cartoons etc., – I wish we had not got rid of this timber (probably used as logs in the winter of 1947!). On one occasion one of the airmen brought back the broken blade of a Hurricane that had crash landed, it burnt very well, especially the coating! For war work my friend’s Mother used to sit at a strange hand machine and cut out bits of silver and cellophane into little strips – later I found that she must have been making mica capacitors! Other war work was going round selling savings stamps and we children would collect any scrap paper to take to school, the reward was a small badge with an army rank inscribed on it.” John Lyne

An old newspaper cutting from the Winton Collection

The Airfield

There were a significant number of RAF personnel billeted in Shoreham during the war. The Sussex Pad was taken over as the officers’ mess and Ricardo’s for the sergeants’ mess which did provide some sleeping accommodation but all the other servicemen were billeted around town. Shoreham airport was classed as a minor airfield but nevertheless played a significant part in air/sea rescue when a flight of Walrus and Lysander aircraft of 277 Sqdn RAF operated to rescue downed aircrew from the channel. F/O Dizzy Seales who was stationed at Shoreham returned after the war to make it his home. An early air gunnery simulator was installed in the dome at the north side of the airfield (it still survives) which was used as a training facility for many hundreds of RAF Regiment gunners who trained at the dome and moved on.

Residents still recall a number of crash landings that occurred :-“Living close to the 025 runway approach (the east/west runway that was then in front of the control tower) we would often see damaged Hurricanes coming in to make emergency landings, there would be small holes and bits missing and fabric flapping in the slipstream. I vaguely remember one occasion when an aircraft fired off some rounds but don’t recollect any damage done. In Connaught Avenue we had a good view of the Lysanders, Walruses and Austers that flew low overhead when landing at the airport. A Hurricane made an emergency landing at the airport but ended up in the river and a Blenheim bomber also attempting to land did not make the airfield and crashed near Lancing College, I think parts of the cockpit glass and support ended up later as swapping material.” John Lyne

Children’s’ Wartime Collections

Like many young lads during the war years shell, bullet and even crashed aircraft fragments continued to be avidly collected as John relates: – “The various bits and pieces we brought to school were incredible and some downright dangerous…we had incendiary bomb fins, 303 cases (some complete with shell and were still ‘live’) shrapnel shards, military badges and buttons and once someone brought in a complete incendiary bomb with its aluminium case distorted by the impact. Once someone got hold of the sticks of cordite from a shell which was much larger than the cordite in bullets, of similar size and appearance to spaghetti …… unfortunately we did not see him ignite it … bullet cordite was exciting enough but that would have been amazing! Less exciting swaps were the pre-war ‘fag-cards’ which we also played ‘flick’ with and if you landed your card on your opponent’s card you claimed it. When cards were not available we would play with the round cardboard half pint milk bottle tops that had a hole for a straw punched in the top.”

Brian Bazen remembers another very risky situation when his next door neighbour at 25 Eastern Road, Colin Piper, put a live bullet in its case in a vice, tapped the end causing the bullet to fly out. Luckily no one was hurt but on another occasion one Shoreham boy picked up a hand grenade which blew off his arm. He survived but had to have a false arm fitted.

German and Italian Prisoners of War It wasn’t just bomber aircraft that visited Shoreham – during the ‘Battle of Britain’ Brian Bazen saw a low flying German plane, a Messerschmitt ME 109 so low the aircraft’s markings and the pilot could clearly be seen, being chased low over the rooftops by one of our fighters. It was shot down and crash landed on the Downs but the pilot was saved and captured. The plane was later brought into town via Eastern Avenue where the children there, as always, took the opportunity to pull bits of piping from it to add to their collections.

Brian worked at Southlands hospital later in the war during which time a captured German airman with a hard attitude was brought in. Knowing a little of the language Brian was asked to translate in an effort to get information for the Red Cross to enable the man’s relatives to be informed. Being an ardent Nazi he would only give his name and number, wouldn’t answer any questions and became quite aggressive eventually having to be restrained. This was the same instance involving nurse Mary Maple who also remembers the pilot as having unreasonably objectionable Nazi sympathies, so much so that whenever the air raid warning sounded he would give the Nazi salute. His continually offensive attitude became too much for the young soldier guarding him and Mary was later summoned by the prisoner to complain that he had been struck by him. The bruise was obvious but Mary, herself frustrated by the German’s constantly aggressive manner, advised the soldier that if he had to ‘restrain’ the man again to do so where it didn’t show!

Gerry White tells of another German fighter aircraft incident when Corporal Frank Dorey or ‘Boots’ as he was known locally, was an aircraft mechanic with 92 Squadron a Battle of Britain fighter unit. He was on leave in Shoreham when another M.E.109 was shot down and crash landed in a field at New Salts farm. Using a service pistol Frank said to the pilot “Hande Hoch”, the pilot replied in good English “I have my shaving gear with me” and from the cockpit of his aeroplane picked up his towel, soap and a razor. Frank then handed his pilot over to the RAF Regiment who arrived to arrest the pilot. The fellow explained to Frank that he always carried his shaving kit when flying as he never knew where he would land.

The crashed Messerschmitt at New Salts Farm (photo Sussex Archaeological Society PP_SHORM_92.1809)

The crashed Messerschmitt at New Salts Farm (photo Sussex Archaeological Society PP_SHORM_92.1809)

Shoreham was also host to other, more permanent prisoners of war and Adur Lodge housed mainly Italian POWs doing manual farm work. They wore clothing supplied by the War Office with distinctive arrow motifs and patches sewn at their knees as a target to be shot at if they tried to escape. They were never a threat though and are especially remembered by residents as having good singing voices.

Shoreham’s Answer to the Food Shortages

Posters such as those encouraging the “Dig for Victory” campaign, “Is Your Journey Necessary? started appearing around town and national security posters like “Careless Talk Costs Lives” and “Be like Dad – Keep Mum” were also pasted up. As the German U boat campaign sank more and more shipping so the importance of saving fuel and growing more food like vegetables became important. Farmers’ fuel was dyed with a special colour to enable it to be identified by the Customs authorities. There were many shortages of all types which were reflected by long queues at all retail outlets. Foodstuffs such as cheese, eggs, butter, sweets, meat, and other goods like clothing were strictly rationed.

John Lyne’s father was a torpedo instructor in the RN who had seen action at the Battle of Jutland and, now in the Reserve, had been in the Dunkirk evacuations on a paddle steamer the ‘Medway Queen’ that the Navy had commandeered. Shortly after that he was posted away, fortunately he returned unscathed. “He would frequently reassure me that we would shortly win the war and that then we would be able to buy chocolate and bananas (things that I had never seen apart from people slipping on them in comics!) There were several Cadbury and Fry’s chocolate dispensers on Shoreham station platform but they were always empty. Sometimes we would listen to Lord Haw Haw on the radio I remember saying that perhaps we should leave the radio on all night as it would waste the Germans electricity – the loud laughter no doubt impressed this incident in my memory.”

As a consequence local children soon latched on to other opportunities to supplement their diets and John Lyne recalls:-“After school we would often go round to the Grammar school building in Pond Road which had been commandeered by the Canadian Army then wait by the kitchen window which after a while would open and we would be given large square ‘hard tack’ biscuits – I guess they thought we were starving! Rations were meagre but families turned to keeping chicken and ducks, there was an allocation of chicken feed by the Government and this would be boiled up with old potato peelings and food scraps and ‘donations’ from non-chicken-keeping neighbours in exchange for eggs, nothing was ever wasted (I can smell the unpleasant odour of chicken feed being boiled up now!)

We would also go into the countryside to collect mushrooms, whatever fruits were in season and rose hips which were sold to chemists to manufacture rose hip syrup. We also went to the river bed near the Norfolk Bridge which had a good source of protein in the cockles, mussels and winkles that my Grandfather and I collected. The Swiss Cottage grounds had a good supply of beech nuts but I never found a local source of chestnuts apart from the park, but was always too late for those! Citrus fruits were rationed if you could get hold of any and fruit juices non-existent; we had never even seen a banana apart from illustrations in comics of people slipping on them…..babies had small bottles of concentrated orange juice issued for them.”

The Battle of Britain and Doodlebugs

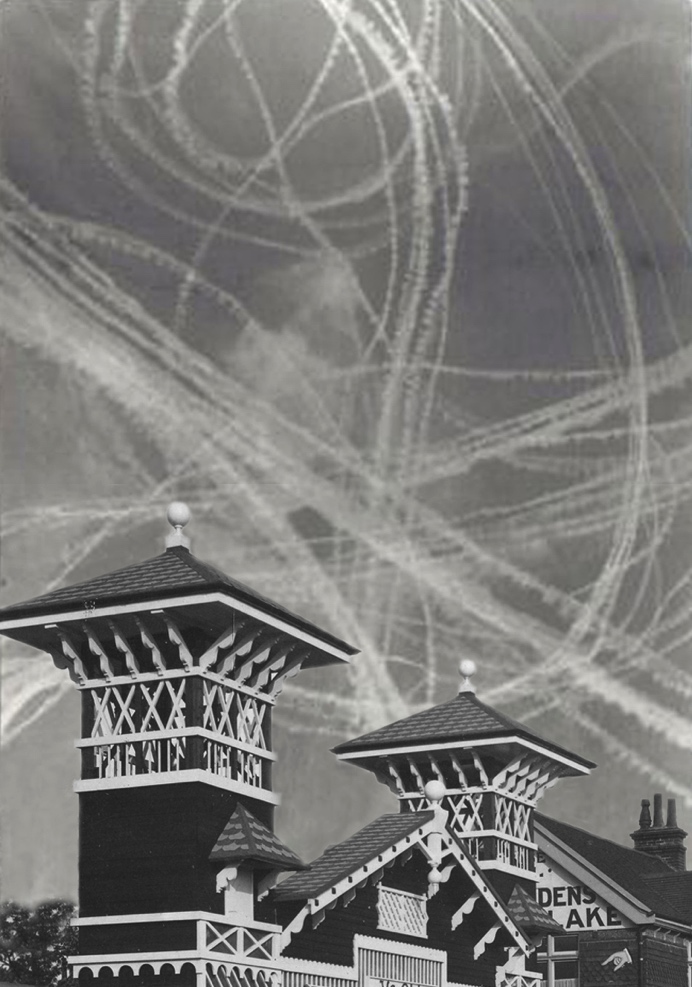

During the fine summer weather of August and September of 1940 during the Battle of Britain it was a common sight to see masses of twisted and looped contrails in the eastern sky in evidence of furious dog fights over the Channel and the distant chattering of the aerial guns in conflict overhead. It was not unusual for empty bullet cases to fall to the ground which were collected as always by Shoreham’s children who made bows and arrows tipped with the spent bullet cases and fired into the air in the local park in the hope of bringing down a German plane or two!

The condensation trails of a dog fight above the Swiss Gardens entrance (composite picture Roger Bateman)

Generally, Shoreham was not bombed as much as other nearby towns such as Brighton but official records do show that during one memorable incident on the 5th November 1944 bonfire night ‘a Doodlebug exploded by the Green Jacket although there were no injuries.’ This fell onto allotments opposite the park where St Nicholas school in Eastern Avenue is now:- “It was early evening on the 5th of November and my Father who was on leave was relating stories of the 5th celebrations in pre war days, the fireworks and processions etc., then we heard a staccato roar gradually getting louder, knowing what it was and not having enough time to get to the shelter we all dived under the table as it got closer, then seemingly overhead the engines cut out and after a few seconds a very large explosion that burst in our French doors against the curtains, the taped glass was intact but the door latch had sheared off. The explosion was about a mile away over fairly clear land, and there was a fair bit of damage to windows in Eastern Avenue. Nearby, neighbours were in their hall when the front door was blown up the stairs by the doodlebug’s blast and they spent the next couple of days picking glass out of the banisters with tweezers.” John Lyne

The blast must have been significant as the shock wave of it was felt as far away as, and within, the Coliseum by The Ham. Mrs. J. Lawrence was there at the time and the blast was so strong that her friend was thrown down the balcony stairs by it. No one there was injured either and the film continued nobody left and everyone carried on watching the film.

“ Subsequently there was an increasing number of doodlebugs overflying Shoreham, to my knowledge no more crashed here but it started to be a common sight as they seemed to fly so low, hardly clearing the south downs.” John Lyne

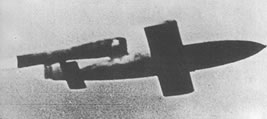

A German V1 ‘doodlebug’ – one like this fell on the Ham Field allotments.

One V1 narrowly missed Lancing Chapel when it came down on 13th July 1944 and Brian Bazen actually saw a Doodlebug being nudged by the wing of a British fighter, and watched it turn back out to sea. This practice was not that unknown and of course dangerous for the pilot but Brian actually saw it happen! A Spitfire from 277 squadron then based at Shoreham shot down a V1 flying bomb on the 4th July 1944 over Beachy Head. The squadron had previously shot down another two on the 30th June 1944 and accounted for five 5 V1’s in total.

Removing Railings and Collecting Aluminium

One morning a couple of lorries arrived in Connaught Avenue, workmen disembarked and using oxyacetylene cutting equipment removed all the steel railings and gates from the houses then proceeded down the road and cut off the large railings at the Swiss Cottage (you can still see the signs around Shoreham and until recently the melted stumps on the Swiss Cottage wall.) – these, residents were told, were to be melted down to make tanks for Russia!

Residents had long been encouraged donate pots, pans etc., at various collecting points around town in order to provide more aluminium for building aircraft. Money for the war effort was raised many different ways – collections, fetes, fairs and at Smiths fairground in the Old Shoreham Road Tom Smith, the fair owner, raised sufficient monies at his fair for the National Spitfire Fund sufficient to buy a Spitfire and was presented with a certificate for doing so.

Virtually everyone made sacrifices where they could for the war effort donations even including a very young Bungalow Town resident Alex Robertson who’s aluminium pedal car was taken for re-use, it was said, towards building a Spitfire!

Virtually everyone made sacrifices where they could for the war effort donations even including a very young Bungalow Town resident Alex Robertson who’s aluminium pedal car was taken for re-use, it was said, towards building a Spitfire!

Towards the end of the war some Bren gun carriers and light tanks stopped in Connaught Avenue tearing up the tarmac a bit. There was a low carriage holding a very large bomb on display and the idea was to purchase savings stamps then stick them on and ‘post it’ to Germany. “One soldier told me that it was going to be dropped on Hitler’s house so I stuck my stamp with several others right on the nose tip! Before the tanks moved off we collected a couple of flints and put them between the wheels and tracks and watched them splinter and fly off in all directions as the tanks moved off.” John Lyne.

French Canadians and Dieppe

As the war continued soldiers from Canada were stationed in the south coast barracks at Brighton, Worthing and in other coastal towns including Shoreham. Many women found the young handsome Canadians with their smart uniforms and laid back style an opportunity to marry and begin a new life in far off Canada. In 1942 a plan for a large scale invasion of France was made when the briefing of Royal Marines and Canadian soldiers took place in the airport terminal building. The target was Dieppe. Although losses were high the lessons learnt from Dieppe raid provided High Command with a better idea of strategy and planning for the eventual invasion of Normandy.

“French Canadian troops were billeted in the Shoreham Grammar School playing fields (now Greenacres) prior to the Dieppe raid and we saw a scaffolding frame put up there just south of the cricket pavilion and we would watch the soldiers with heavy packs climb up and cross hand over hand along the horizontal poles – later we went over and did the same on the lower pole. I heard later that some troops were drowned in the river Adur when a boat

overturned during their training. I also remember walking over to the Airport with my

Mother to deliver something to the guard room and seeing a large number of barges moored under a framework of camouflage netting at the Shoreham end of the toll bridge where there were a couple of armed soldiers patrolling the area ‘moving people on.’ On another occasion in this area I could see a lot of inflated rubber guns and tanks parked outside the terminal building, even from that distance you could see that they were not real as they tended to sway in the wind!” – John Lyne

The cricket pavilion on the Grammar School playing fields

(photo John Lyne)

The Allied Invasion

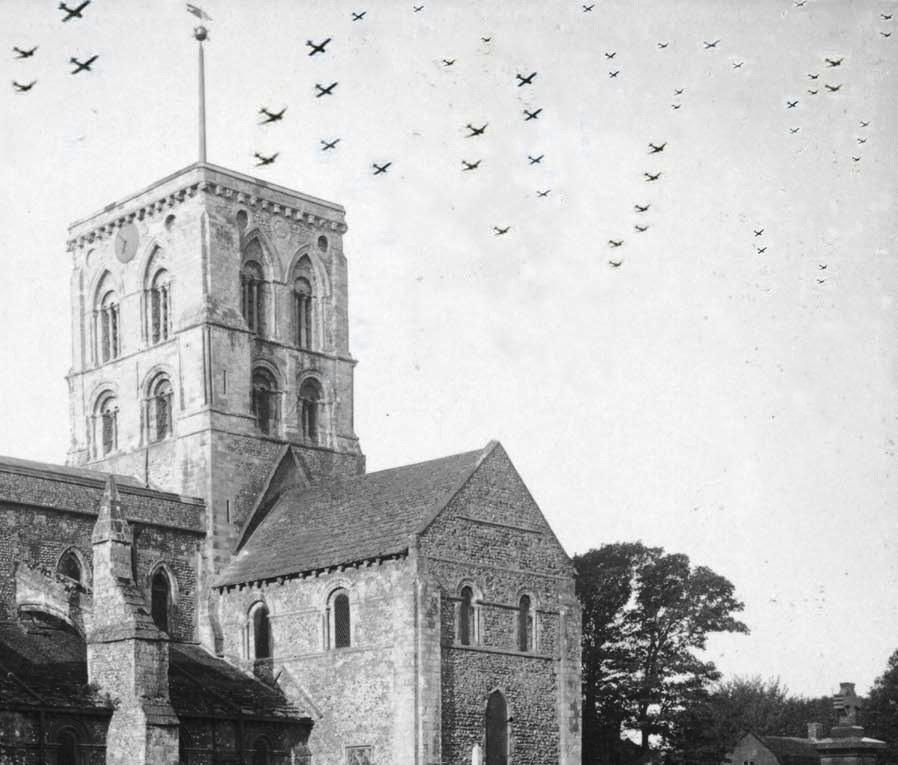

John also tells of the invasion preparations: – “There were invasion barges under camouflage netting moored by the Old Shoreham toll bridge which must have been around D Day and this was when I saw a procession of large gliders being towed by ‘Dakotas’ over to the west of us. They seemed to be two or three in each tow and looked very large and ungainly flying very slowly.”

D-Day invasion gliders above St.Mary’s church (composite picture Roger Bateman)

Seeing all these aircraft together was nothing new to the people of Shoreham and on occasions even produced a strange phenomenon. Following America’s entry into the war massed formations of B-17’s and B-24’s would rendezvous and circle high over the town before flying on to their targets. As more and more aircraft gathered the increasing number of condensation trails on a sunny day soon made the sky overcast.

“Being so young I had no idea about the progress or details of the war but was assured that we will win! My Grandfather was always tuning in to ‘Lord Haw Haw’ with his grating nasally voice ‘Germany calling…Germany calling’ and the BBC European Service with the call sign of a drum sounding dot, dot, dot, dash ‘Ici Londres’ I would listen but for me none of it made any sense!” John Lyne

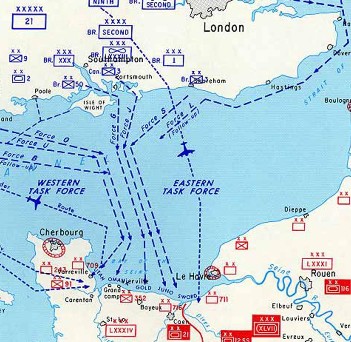

Like many other towns on the south coast during the weeks leading up to D-Day Shoreham was host to many troops with their tanks, guns, lorries and equipment that were parked in the roads and lanes above the town. Soldiers were billeted around town and in parts of Southlands hospital for a short while which caused severe overcrowding to the extent that many had to sleep against the walls. Efforts were made by the locals to provide some comfort and refreshment for the army and in Church Street soldiers could walk down the passage alongside the Co-op store then behind to the old scullery at number 11 for tea and biscuits. All these troops and equipment were part of ‘S’ Force that set sail from the huge number of ships and craft moored in Shoreham harbour bound for Sword Beach in Normandy.

D Day invasion map showing ‘S’ Force’s route from Shoreham to Sword Beach

Inevitably, some troops were more than just popular with some of the townsfolk: – “A few ‘goings on’ have been reported by a reliable source who for the sake of her remaining virtue shall remain nameless! A lot of people seem to have had a very good time indeed!” Gerard Downing

Victoria Road School and St.Wilfrids

“I started school in Victoria Road just before the end of the war… I clearly remember the small air raid shelters in the infants’ playground and the drills we had to do to be able to get into them very quickly. I think there were three – one for the ‘babies’ and one each for the other two classes – they were a bit like this:-

This was in autumn 1944 though so I suppose there was still that fear of bombing raids. The ‘junior playground was like an inner yard. But I remember the ‘end playground’ where the main vehicle entrance was on Connaught Avenue and that had metal railings and gates right up to the corner opposite the Hebe where they joined (if I remember) a flint wall up to where the houses began. I also loved going out into the Meads at the back to play once a week and can still remember being made to have a ‘sleep’ on a mat on the classroom floor after lunch every day (we were only ‘nearly’ five after all!). I adored Mrs. Handmore my teacher – she wore a brightly coloured overall which seemed so exotic to me.

I have a great many memories of growing up in Shoreham….the International Stores where they still had the ‘pull string’ little carrier on overhead wires to take the money to the cash desk in the corner – and I can still remember my Mums ‘divi’ number – 22625 (once learned – never forgotten….) which you had to give to accumulate some savings on your purchases. These were entered in your ‘Dividend Book’ and were (in our house) saved for Christmas treats. Such things a ‘whole’ biscuit! No don’t laugh…we couldn’t afford them normally and the International did a great trade in ‘broken biscuits’. All their biscuits were displayed in glass topped tins at the front of the counter and I used to dream about actually holding and eating a whole biscuit!” Carole Bienati

Some youngsters were not so fortunate as to have a home life then, Dorothy was taken to St.Wilfrids children’s home with her brother. “I was 12 years old and I lived in the childrens home in Ham Road, I didn’t like it there and ran away several times. The furthest I got was Hove and it was middle of the night and I was so tired that I went to a house and told the lady I had runaway I was taken to Hove police station and then back to the home. On another occasion when I ran away it was pouring hard and I was walking along the road toward Portslade, there was some sort of depot on the left, anyway there was this chap coming out in a lorry, he called to me and asked if I wanted a lift and I said yes, he asked where to and I told him my home address so he said OK, but he drove me to Shoreham Police station which was in a little road somewhere near the Church and so I didn’t get far that time, I often think about that and how if this driver had been a nasty character who knows what might have happened to me.

The housemother was very strict with me for some reason and once hit me in the nose causing it to bleed, I think this is why I kept running away – after the last time I was questioned by someone in authority why I kept running away so told them about the housemother She must have got the sack because we got a new one and she was a very gentle loving person and I was much happier.”

“In due course I progressed to the ‘juniors’ and can remember that we had a boy from St. Wilfreds in our class – he seemed to cry a lot. Having read Dorothy’s memories after 60 odd years I can maybe understand why.” Carole Bienati

I used to play in Buckingham Park and on Mill Hill, I remember there was an empty house that we had been told was haunted and my friends and I went there. To get to the house we crossed over the railway station and the road was the first on our left (the start of Queen’s Place). While walking round the grounds I suddenly saw a hand appear at one of the windows which scared the wits out of us but we went back another day and found a way into the house – suddenly there was the sound of a piano being played from a room upstairs which was scary too so we never went back. I can also remember that on several occasions I and some friends would walk across the old bridge that leads to Lancing singing at the top of our voices ‘Rule Britannia,’ goodness knows why or where we were heading for.” Dorothy

The War End and Celebrations

In 1945, following the collapse of the Third Reich the war in Europe came to an end. The bells of St Mary’s church rang, public houses were open all day and the chairman of the Urban District Council announced the cease fire from the town hall in the High Street. Servicemen returned. New but very unfashionable demob suits were seen on building sites as men returned to work. The street lights were switched back on and double summer time was reduced to one hour. Street signs were put back and the business of clearing mines from the beach began.

“At the end of the war there was a VE Day party for Children held at the top of the Connaught Avenue green. I can’t remember much about it and I doubt if there would have been much in the way of sweets, jelly or ice cream due to the rationing but I guess that we enjoyed it. I think that my Grandfather, who lost two sons in WW1 but thankfully none of his family in WW2, did his celebrating at his local the Hebe pub.” John Lyne

“I remember that the house called ‘Belmont’(number 14) at the eastern end of Western Road on the north side which had steps leading up to the front doors. It is one of a pair of houses and they both had cross tapes on their windows. On V.E. day (Victory in Europe day 1945) a V for victory was painted on the right hand wall by the front door of Belmont – the ‘V’ was about 18″ high and is still there.” Gerry White

The beach was open for swimming again in late 1946 but it was to be sometime later before residents with those few bungalows that had not been demolished were allowed to return.

It was to take many years for Shoreham to get back to normality and the old town looked very tired after five long years of war.

Editing and additional research by Roger Bateman

Shoreham

October 2010 (Revised November 2015)

I was born in Shoreham on 12th August 1945 and was trying to see where the hospital was located, when I found your interesting article. Such fascinating reading. I remember, as a child, visiting some of Mum and Dad’s friends [Gaye and Dennis] who lived by the Golf Course [I think] in a bungalow which had a marvellous view. I now live in Australia, but, when I have been in UK, I visit an Aunt who lives in Henfield and travel by train from Devon to Shoreham. I always have that coming-home feeling when I get to Shoreham. My Grandparents lived in Steyning during the war and Dad used to tell a funny story about some of his friends who also lived there and told Dad about this amazing sight. Apparently, the friends saw a German aircraft flying over them surrounded by British aircraft. They were baffled because the RAF didn’t shoot it down. Dad informed them that he was very glad they didn’t do so because, he was test flying the captured aircraft and the other aircraft were protecting him!

My grandfather George Ansell was Stationmaster and in charge of the Airport during the war. Somewhere in the paper there was a photo of him greeting Winston Churchill on a visit to Shoreham.