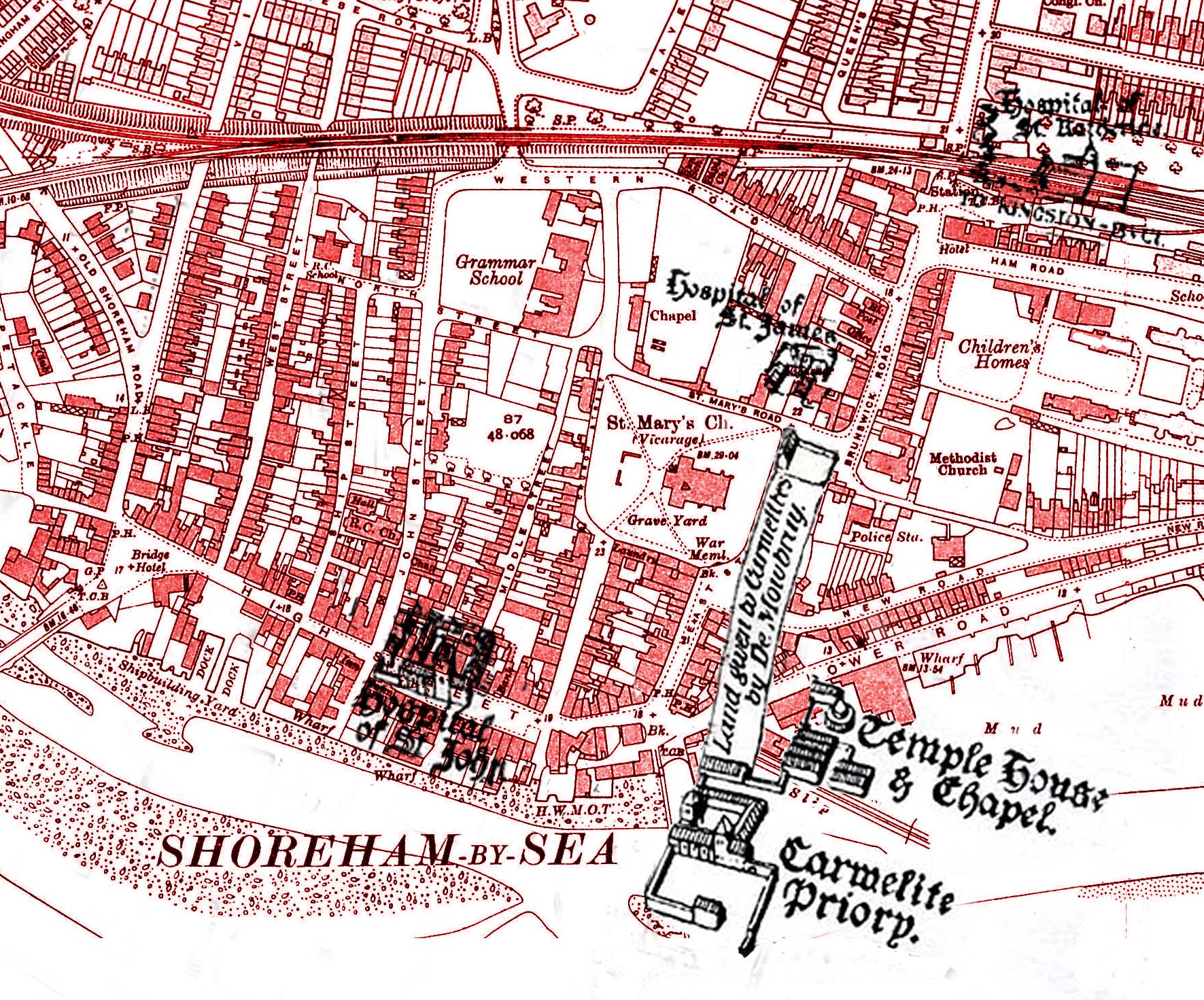

– an alternative view of mediaeval Shoreham and the location of buildings within it

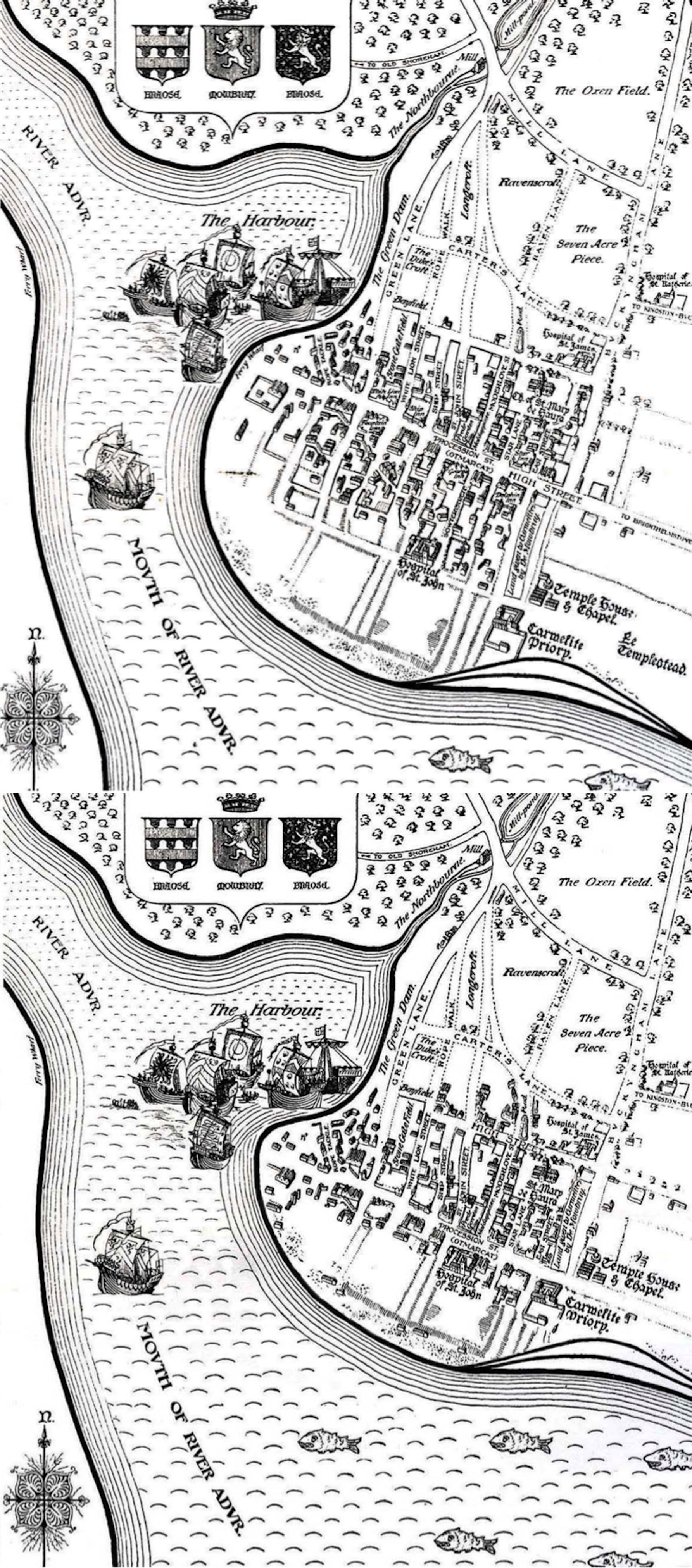

Henry Cheal was, and is almost certainly destined to remain, Shoreham’s leading authority concerning the town’s history. By his own admission much of his conjectural map of mediaeval Shoreham was based upon educated assumption largely from clues discovered in ancient records. This paper, using many of the same archives he used together with research and opinions of more recent reports is not intended to disprove his views but merely to suggest possible alternatives to them.

St. Mary de Haura, Marlipins and St.Mary’s Cottage

These three surviving mediaeval buildings provide excellent reference points with which to identify more precisely the location of other now defunct contemporary structures. Unfortunately none of the records for the other buildings so far unearthed appear to mention their proximity to them (save for the Prede Garden land alongside Marlipins – see ‘St. John’s Hospital’ below). St. Mary’s Cottage is first mentioned in 1150 as the most likely building given to the monks of Sele by William de Braose – the history of the other two has already been comprehensively covered elsewhere.

The Size of the Mediaeval Town, the Carmelite Priory and Knights Templar Religious House

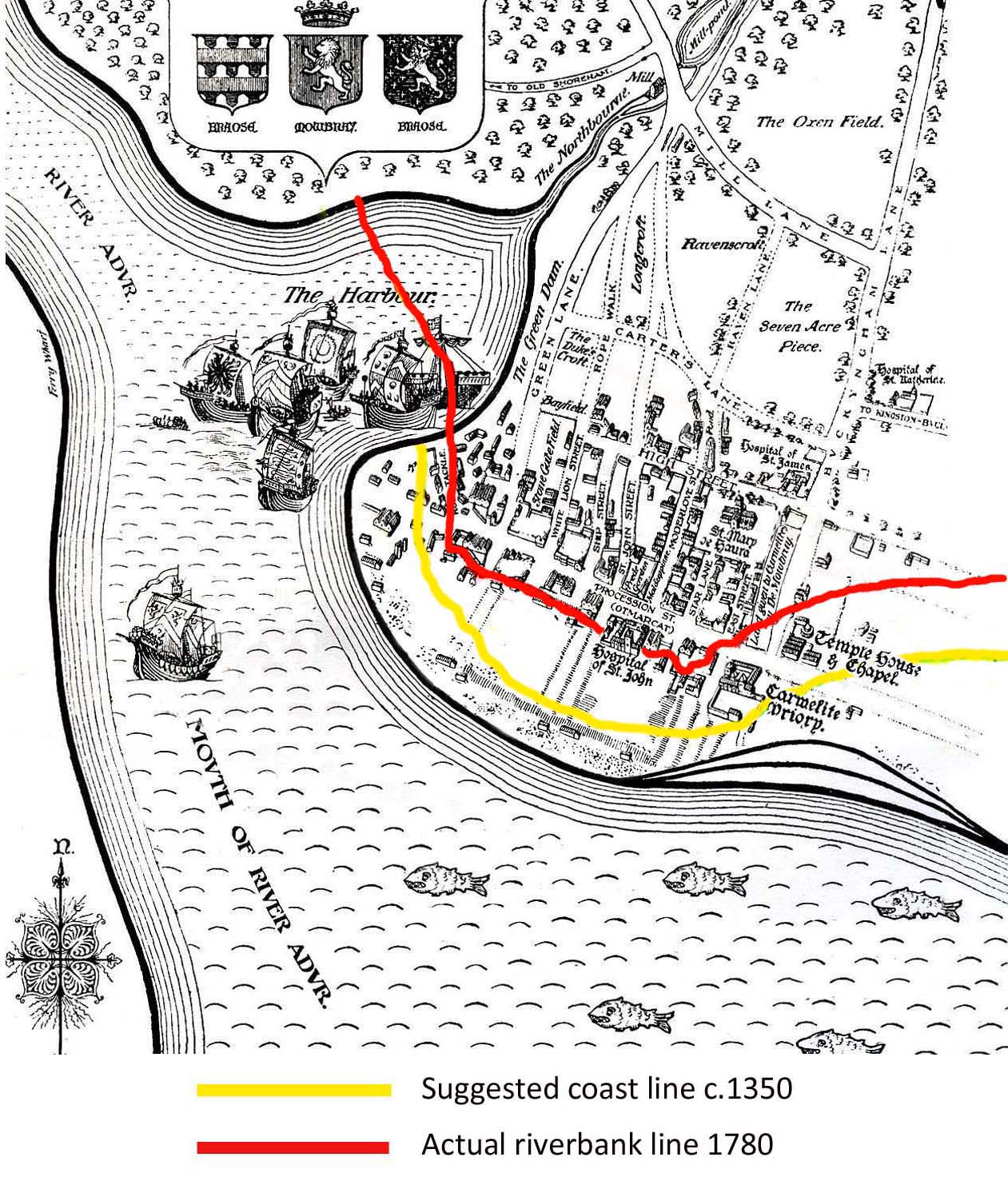

Twentieth century author and leading Shoreham historian Henry Cheal’s reasoning for assessing the southern half of the medieval town together with the sites of the Carmelite Priory and the Knights Templars’ house appears to be largely based on Sir John de Mowbray’s 14th century gift to the Carmelite Priory. This acre and a half of land (commonly believed to be one acre long and half an acre wide, similar to the shape and size of land between Shoreham’s old streets) was “to enable them to enlarge their house………… on the sea coast to the east of the town.” The deed recording this shows that before the gift of the extra land the north side of the Carmelite property lay at least a furlong south of the High Street (3a). It would appear that Cheal uses this furlong guide as a measurement upon which he bases the minimum size of the town below the High Street and, from the proportions indicated by his map, a maximum of about 2 furlongs.

Using this basis his interpretation of mediaeval Shoreham included a substantial area south of the High Street that was in size at least as much again as the other half of the town to the north of it and larger. This view is supported by William Camden when writing of New Shoreham in his 1607 publication “Britannia” who held that “The greater part also being drowned and made even with the sea is no more to be seen” – albeit written some 200 years or so after the worst of the erosion had occurred. Cheal also made the logical assumption that the numerous hards leading off the High Street were once themselves streets, opposite their counterparts to the north. However, this assumption and the extent of the lower part of town has since been questioned by later thinking.

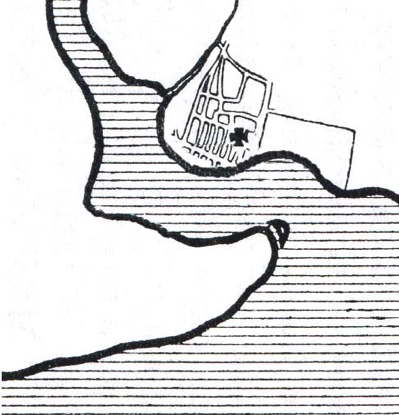

The 1980 Volume 6, Part 1 of the History of the County of Sussex (part of which is included at the end of this paper) written by a group of noted researchers assisted by Sussex historian Dr. Peter Brandon, makes an opposing argument to suggest that the erosion by the sea and river (before the beach spit had formed) of the town had not been as great as commonly believed and that the medieval High Street had been in fact much farther north.

In medieval villages and towns the church was the focal point situated in the main or high street. For New Shoreham this would have been St.Mary’s Road westwards including North Street, the northern half of the town above that and the southern part below. The road we know now as the modern High Street was in mediaeval times called Procession Street, a name that elsewhere was the name for a periphery road, not a central street.

Applying this concept to Cheal’s mediaeval map (page 3) and re-siting the High Street on it to St. Mary’s Road would immediately reduce the southern half of the town but still with streets matching the northern portion and still enough to warrant Camden’s earlier description of it – something that may seem more reasonable to accept by some assuming a lesser amount of land loss to the sea and river. What is now Brunswick Road is thought to have continued down behind today’s East Street and the latter just a path alongside the churchyard – the amended version reflects this path whereas Cheal’s map does not.

Another rough indication is the extent of coastal erosion over the past two millennia. It is thought by many that the coast in this area during Roman times was about a mile further south than it is now. Of course the gradual wearing away of the shore was never at a constant rate but over such a long period some idea the average rate can be gauged. The first indication we have of inroads by the sea is in 1348 when Sir John Mowbray gifted the land previously mentioned as the property then already held by the Priory (i.e., their existing land further to the east?) “is subject to devastation and destruction towards the east by the ebb and flow of tides and is likely to become a ruin….” The following is perhaps an over simplification and certainly very approximate but the Priory building finally disappeared by about 1500 so over a period of 150 years the sea advanced from being just a threat to complete ruination of the building. If a mile of coast had been lost up to then the loss in those last 150 years was more likely to have been something less than one furlong.

We do know from John Kingswoode’s 1330 documentation which also gifts land to the Carmelite Priory that the latter stood very near or next to the religious house of the Knights Templar. It positions the land “under the temple” with the marsh of the Templars called “le Templestead” to the east and north. Cheal placed the Priory and Templars’ House near the south end of today’s footbridge but allowing for the Carmelite Priory to have been one furlong from the medieval High Street above St.Mary’s church now places it and the Templar house either side of the route eastwards before it was washed away. Overlaying the 1782 riverside line still shows that both sites were then covered by the river but following certain land reclamation since then on the north riverbank now places the Templar site around the area of the Sussex Yacht Club with the Priory just off the south-east corner of Coronation Green.

Henry Cheal argues that the pronounced irregular shape of East Street is not repeated in any of Shoreham’s other streets and was therefore not part of the town’s original street plan. He offers the view that this was caused after the southern half of the street was re-routed following the erosion to the east which also blocked off the now washed away road out of town (today’s High Street) eastwards. However, it could surely be said that Church Street is a similar, mirrored counterpart of it so would have been in keeping with the general street ‘pattern’ – albeit using half-streets. The top half of East Street was believed to have once been no more than a path alongside the churchyard – looking at narrowness of the roadway at the top half of Church Street nowadays it is easy to imagine that too was once just a path.

Cheal also mentions the discovery of ancient buildings’ foundation walls during excavations at the point where, in his time, the buildings on the east side of East Street continued across and blocked off today’s High Street. If the Templars’ buildings were a little more west of the supposed site shown on the erosion map could this have been part of the Templars’ buildings?

St. John’s Hospital.

Cheal placed it about one furlong southwards (without giving a reason for so doing) but in a line with John Street above it as he was working on the premise that the street name indicated the way to the hospital. The repositioning of the High Street now lifts the hospital up to a point straddling today’s High Street but Procession Street, as it was called in mediaeval times, was a thoroughfare and very unlikely to have been obstructed by buildings.

There appear to be four nearby possibilities for the hospital (although no archaeological evidence has so far been traced). The first could have been the land at the south-west corner of the John Street junction with North Street which was long known as “St. John the Walls” and may be the echo of possible occupation by the religious order. The second is the plot on the north-west corner just above that and the third may be the land then known in 1479 as Prede Garden on the south-east corner with the High Street which in the 18th century stretched a considerable way up John Street and fronted the main road alongside the still surviving medieval Marlipins building. All three plots were copyhold, a practice originating in mediaeval times, of the Manor of Lancing in 1782 which meant they were owned by that Manor and could possibly have been bought as an endowment for a religious house.

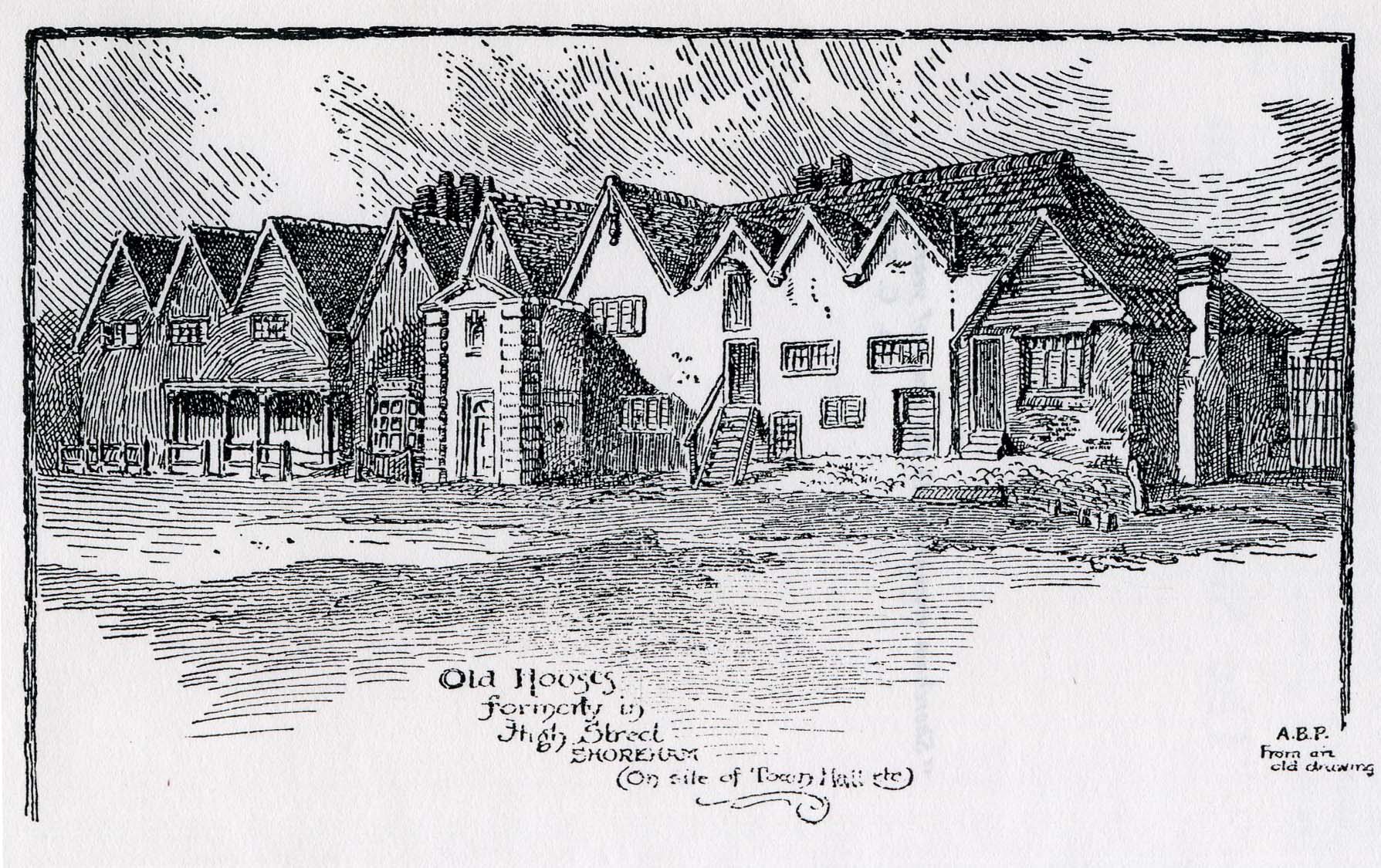

The fourth is the site on the south side of the High Street opposite the John Street junction where now stands the old Town Hall/Custom House which itself replaced the original Poole family mansion house. The latter has an ancient history itself which according to Cheal was about 16th century, possibly earlier which brings its origin to a point in time roughly consistent with the demise of the hospital in the 15th century – is it too fanciful to imagine it to have been part-built with the stones from the older building?

St. Katharine’s Hospital.

This hospital is mentioned in the Subsidy Rolls of 1327 and in various wills from then up to 1466. Cheal suggests that the hospital may have changed its name to “the Hospital of our Saviour Jesus Christ” thereby surviving the Reformation to enable another record of a further bequest in 1550 when the Vicar of Wilmington left 20 pence to “the spytyll.” Mark Anthony Lower M.A., however (the author of the 1851 research concerning that particular bequest) believed it referred to the Hospital of St. James (see below) that survived the Reformation.

The Upper Shoreham Road has long been accepted as being of Roman origin but a mediaeval road is also believed to have existed further south. Cheal suggested that Shoreham’s St. Katherine’s Hospital was situated at the end of this road from Kingston Buci into the town from the east on the basis that examples elsewhere commonly show them to have been built at such places. He does support this though with the argument that Aldrington and Kingston churches are known to have housed anchorites and that the bishops of the time were unlikely to have approved such an arrangement unless the churches were on a well used route in order for travellers to provide the anchorites with food and donations upon which they depended. It is held that this route followed today’s Middle Road which some believe continued on through what is today Nicholson Drive to Buckingham Road but Cheal and others thought it dropped down to meet Buckingham Road around the area of Mill Lane. In fact when overlaying Cheal’s map on to later maps his St. Katherine’s appears further down around the site of the railway station – quite some distance below Mill Lane but no doubt Cheal never intended to indicate that any of the mediaeval locations on his map were precise.

It would appear that Cheal largely based his thinking on part of the article in the Sussex Archaeological Collections by the Rev. Edward Turner M.A., concerning the Aldrington anchorite. However, rather than promoting the view that Aldrington was on a frequently travelled medieval route Turner actually goes on to argue against it by pointing out that Brighthelmstone to the east was then an insignificant town of no particular size so was unlikely to provide the traffic for the route; Lewes and Chichester were “too far distant to be available for gratuitous assistance” and Sele Priory itself was a long way from being a wealthy institution. Aldrington was also known to be a poor parish and Turner comes to the conclusion that the Bishop’s permission was only granted because the proposed anchorite possessed sufficient means of subsistence himself – another reason to permit the arrangement without becoming a burden on the finances of the church.

St. James Hospital.

Nevertheless, he seems to be fairly sure of the site of St. James’ Hospital which is shown on the land bordered by Pond, St. Mary’s, Brunswick and Western roads. Cheal quotes references to the property in 1249, 1296, 1327 then 1524 but, like most ancient property references then, do not describe clearly where in Shoreham it was. He does lay great store though upon the continued usage of old property and land names etc., which have tended to survive for many centuries and provides an example of this with Walter Farley’s 1628 will that mentions his “croft called St. James.”

However, there is still no apparent evidence in Cheal’s writings to be able to place the St. James hospital at any particular spot but now recent researches have revealed mention in 1792 of “two several pieces of land lying together called Saint James and Finches and now called Almshouse Field.” This from the will of Mary Connock who owned the land either side of Pond Road and part of the eastern side is shown in the 1782 Survey of Shoreham as “Alms House Field.” Cheal doesn’t mention the 1792 will but perhaps he either knew of it or had found a similar record. As previously mentioned, Mark Lower M.A., believed St. James Hospital survived the Reformation which adds weight to the survival of the name by the 18th century. There is no known evidence to show that the almshouse itself was medieval but there is mention of such a building in 1549 which may well be the one in Mary Connock’s field. This stood on the corner of Pond and St. Mary’s roads and was incorporated into the later Grammar School chapel.

Roger Bateman

Shoreham

January 2012

References –

The Story of Shoreham, Henry Cheal, 1921;

A History of the County of Sussex Vol.6 Part 1, Bramber Rape; (see extract below)

Sussex Archaeological Collections;

1782 Survey of New Shoreham;

New Shoreham Wills, Deeds etc., from A2A web site;

A Walkabout Guide to Shoreham, Michael Norman 1989

Extract from the 1980 Volume 6, Part 1 of the History of the County of Sussex

It has been ingeniously argued that what survived of the town in the 18th century represented little more than the northern half of the original layout, and that south of the main street there had formerly been, before it was washed away, a pattern of lanes matching that to the north. The argument rests on the evidence of the destruction by water of part of the town, on the reference in the early 14th century to a furlong lying south of the high street, on the correspondence of the openings south of High Street with the streets running north, and on a local tradition current in the late 19th century that the harbour had once been at the back of the town

The tradition has been interpreted as meaning that the main anchorage was the inlet north-west of the town, which later silted up and was marked by the Northbourne stream down its centre line, the boundary between the parishes of Old and New Shoreham. An old dam, apparently across the end of the stream, was recorded in 1612. In the early 17th century what was called the old haven lay west of the town in the north-east arm of the river. Later in the 17th century the south-west arm of the river was marked as the haven. The existence of a haven west of the town, where ships might lie at anchor, in no way denies that the wharves and hards in the early 14th century were in the same place as in the 18th, and since the course of the river is known to have changed extensively the old haven recorded in the early 17th century was not necessarily that of the early Middle Ages. Excavations for drainage in the area of the Northbourne stream have revealed no evidence of wharves.

If it was the southern half of the town that was washed away it is an unusual coincidence that the erosion should have stopped short on a line close to and parallel with the main street. Moreover the lie of the land and the course of the river in the period for which maps are available suggest rather that the land lying east of the surviving town was the area most likely to have been lost, an inference which accords with the documentary evidence of the 14th century and with the discontinuity at the eastern end of the regular layout of the town

The existence of a furlong south of the high street does not necessarily mean that the land there has been washed away if the medieval high street was other than the main street of modern times called High Street. That street was in the Middle Ages called Procession Street, a designation given elsewhere not to the central street but to a peripheral road. The high street of modern times was so named in 1682, though in the mid 18th century it was called South Street and part of it had once been called West Street. If the medieval high street was other than modern High Street it may conceivably be represented by the cross-lane which was the northern limit of the built-up area in the 18th century and was marked in 1976 by North Street and St. Mary’s Road. On that hypothesis the comparatively close network of lanes to the north can be seen as part of the early medieval built-up area, actual or intended, extending to the parish boundary which ran up the Northbourne stream, along Mill Lane, and down Buckingham Road to Ham Road. On that hypothesis also, the church, which was an early feature of the new town of the late 11th century, stood on the south side of the high street fairly near the middle of the settlement rather than at the north-east corner, while the extent of erosion in the south-east corner was more limited than was suggested by the claims made in the 15th century, when inundation was offered as more dramatic evidence of ruin than the contraction of settlement or the decline of the harbour through changes in the coastline.

Someone has suggested to me that a paupers’ graveyard could have existed outside the current eastern wall of St Mary de Haura church.

It was claimed that some human bones were once found in the area of East Street that runs along the churchyard wall.

Given the flimsy nature of the suggestion, I have trawled sources such as Cheal, the 1782 survey, and notes by Michael Norman sent to me by Ian Tompkin, without finding any reference to a separate graveyard.

Do you have any information or comments about this?

I’ve been through our records Tony but can only find a vague reference to it (below) in the John Hindes article on this website. Unfortunately, it doesn’t say where in the churchyard but it is likely that mention of ‘the poor’ would have included paupers.

Extract from Francis Hard’s letter to the Brighton Patriot 20th June 1834:-

“Sir, I am well acquainted with the individual in question and I believe his only crime to be that of supporting, as far as laid in his power, the poor man against his oppressors which has caused him to be a marked man by the strightbacked gentry of Shoreham. In 1834 he attacked the clergy and churchwardens of Shoreham for the unhallowed design of leveling the graves of the poor in the churchyard whose friends were not wealthy enough to erect a tombstone to point out the place where their remains were laid; and also pulling down a wall which they had thought proper to erect for the purpose of stopping an ancient footway across the churchyard. Having defeated them in this case his next …….”

PS Perhaps the Vestry Committee records for St.Mary may help more (if they still exist.0