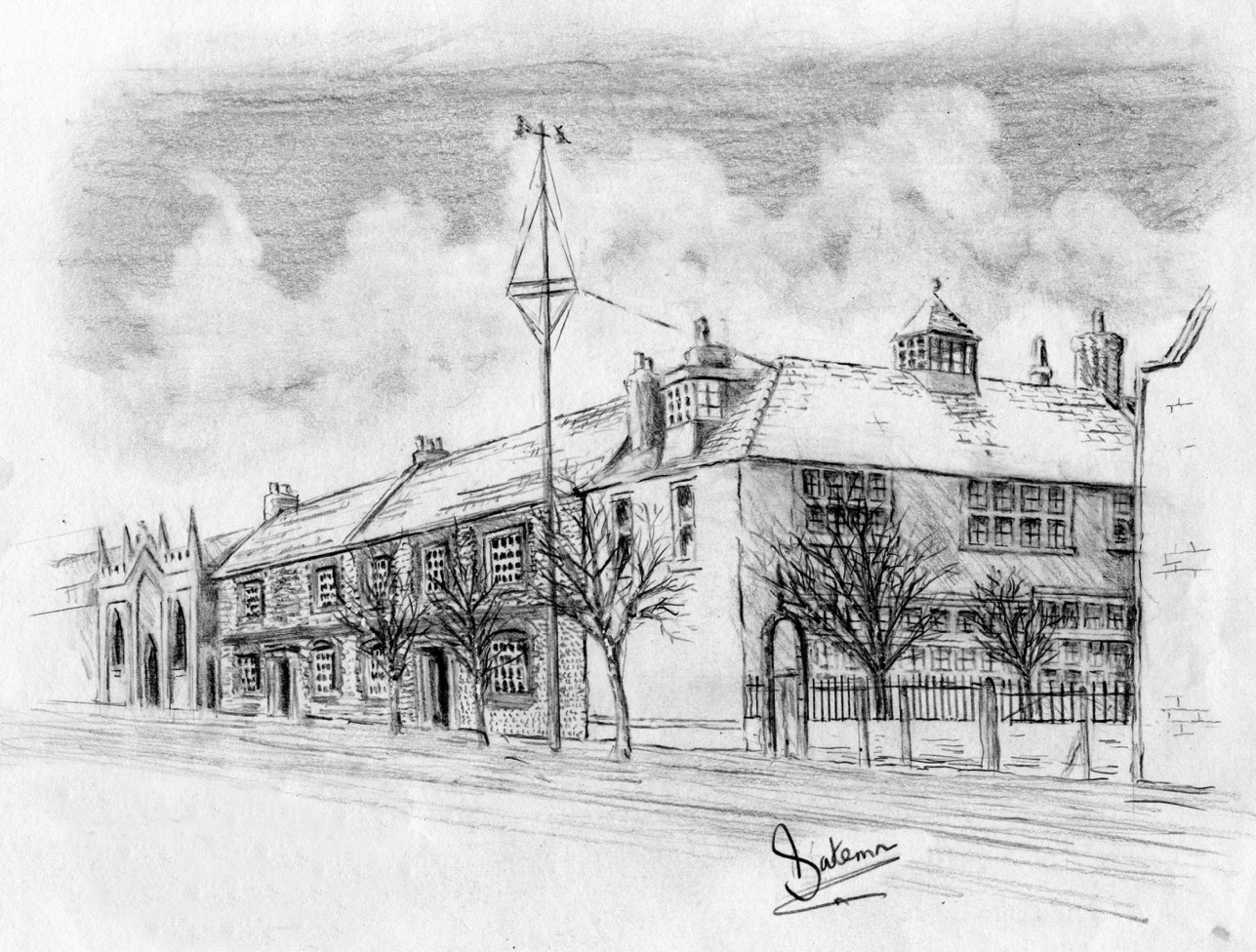

The entire block of houses numbered 13 to 23 in this area of Church Street were built in the1850’s by G.H.Hooper, a Shoreham property developer and descendant of the ancient Poole family of the town. Hooper had previously acquired and demolished the earlier building on the site that was believed to be 16th century. Anciently known as ‘Chantry House (before the later house of the same name in East Street) the southern half was used as the Customs House until the 1830’s.

During the latter half of the 18th and early 19th centuries the northern half and outbuildings were used variously as tenements, malthouse, stables, coach house, granary and a cistern or pump room. A more complete description and history of this building is already included in ‘New Shoreham Houses, Owners and Residents 1782 to 1920’ in Shoreham and Worthing libraries under the section relating to Church Street and all that is necessary here to more appreciate the findings of the excavation is to provide an idea of how the earlier building’s footprint compares with the 1850’s houses.

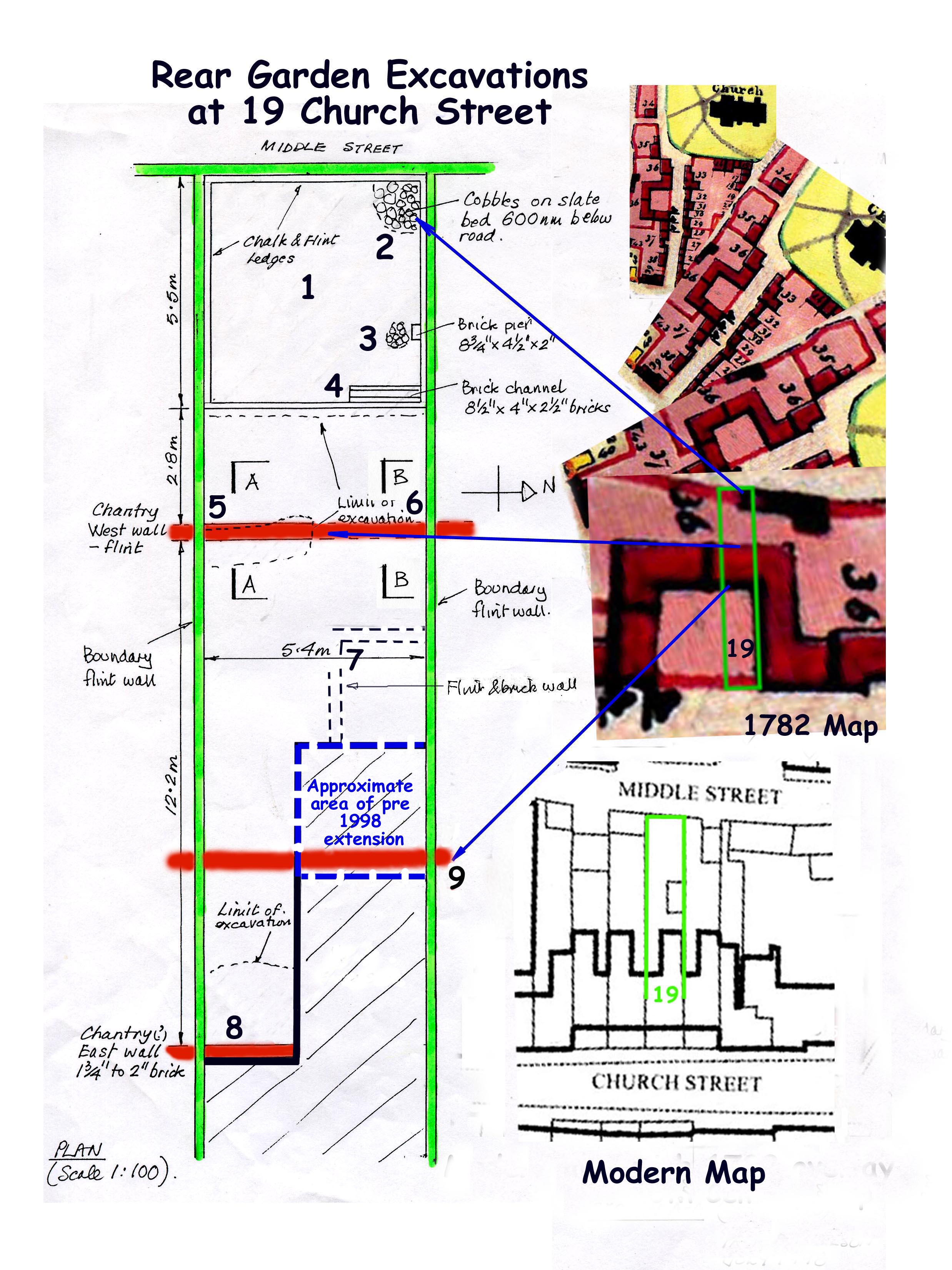

This illustration shows the old buildings from the 1782 Survey map in red overlaid on to a modern map. There was a courtyard fronting on to Church Street and this comparison between the two maps suggests that the southern half (the old Custom House) covered the land on which number 13 now stands. The courtyard extended from number 15 to 19 and beyond it the western end stretched across the rear of these properties then returned again to the Church Street frontage on land now covered by number 21 and continued into number 23 (the remaining buildings 9, 11 and 25 still stand) – an outbuilding stood behind the main building bordering on Middle Street. The 1782 map was drawn in freehand so does not fit precisely on to the modern day map. Nevertheless, the same exercise was carried out for all the buildings in all of Shoreham’s old streets and was found to match surprisingly well.

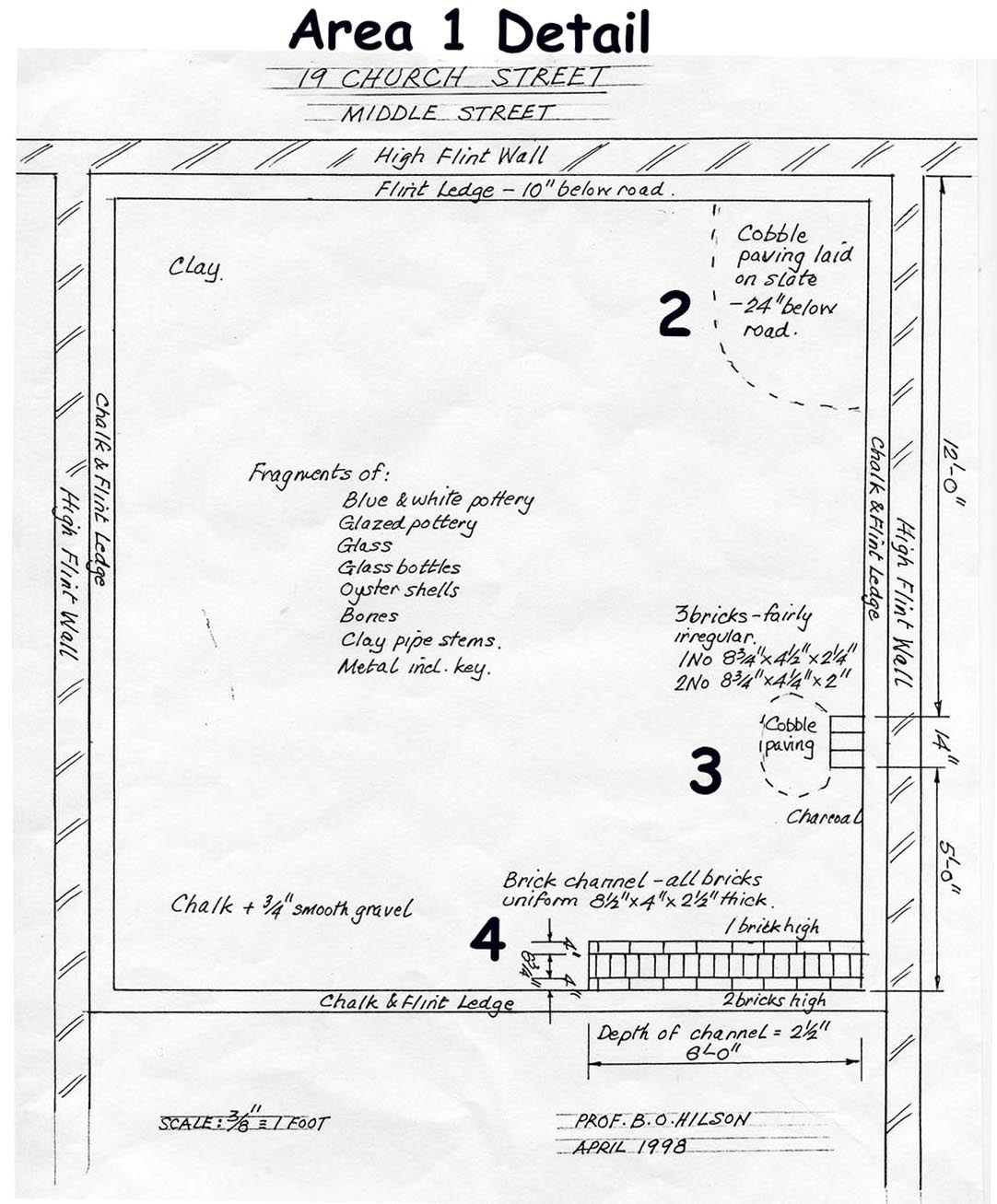

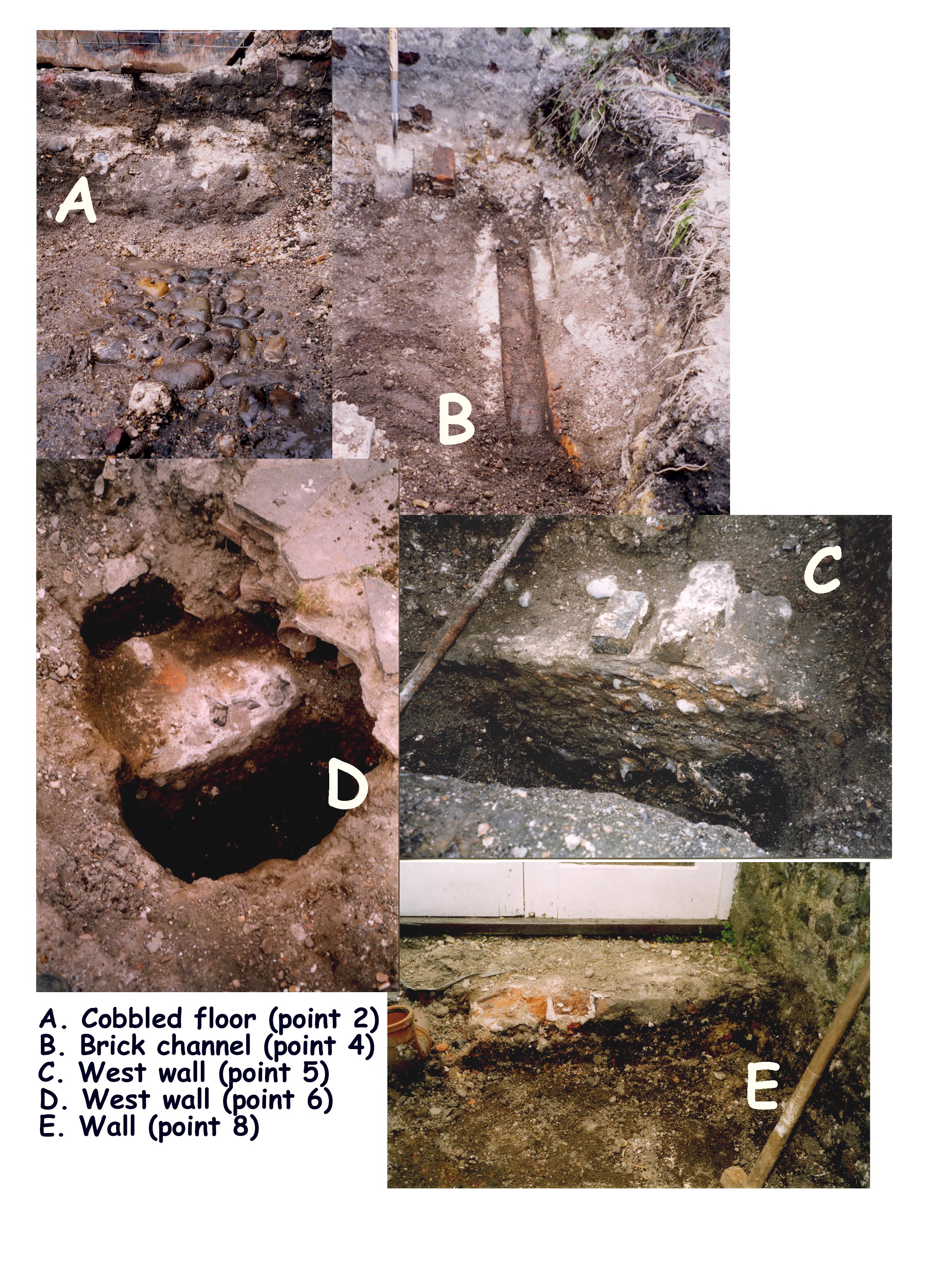

During April to July 1998 the owner of 19 Church Street, Professor Barry Hilson, started work in his garden to build a garage and conservatory. During the excavations a number of historical artefacts and building remains were discovered. Page 3 shows his plan of the garden and excavations. During the course of the excavations the remnants of a cobbled floor on a slate bed (2 & 3) were discovered in the northwestern end of the garden which coincided with the southern end of an outbuilding shown on the 1782 map. At least part of this building was probably used as the stables mentioned earlier and just below it was a brick channel (4) doubtless for the drainage/sluicing down of the stable yard.

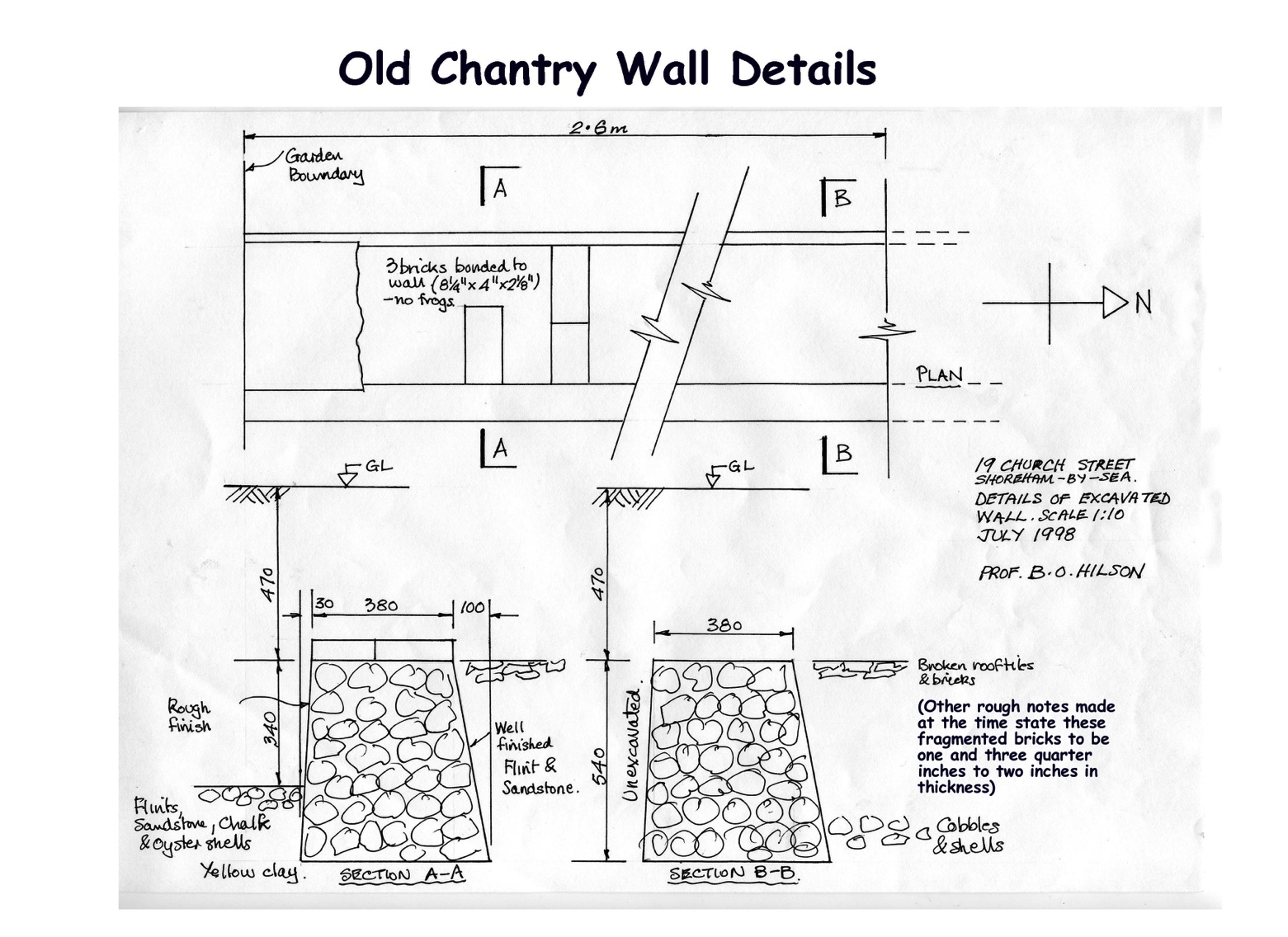

Excavations for the garage soakaway revealed a flint wall generally accepted to be the rear, western wall of the Chantry House (5 & 6). A further flint and brick wall was then discovered a few feet to the east of that (7) which is assumed to be an outbuilding erected after the Chantry House was demolished. This survived until well into the 20th century and still appears (incorrectly) on some current maps (the outbuilding’s foundations were partially built over by an earlier extension to the rear of number 19 some years before 1998), (The wall at point 8 is not now thought to have been the Chantry House east wall)

Foundations for the new conservatory revealed another wall (point 8 on the plan) this time of brick which was thought to be the front, eastern wall of the Chantry House that faced the courtyard. However, the 1782 footprint of the building suggests that the eastern wall was situated further back (point 9 on the plan) in that part of the garden that was not included in the 1998 excavations (earlier excavations for an extension by a previous owner may have disclosed this wall but there is no record of this). Another clue (but not proof) as to the position of the east wall is provided by the author’s survey of the cellar under 21 Church Street that was once beneath the northern part of Chantry House shows that it extended from the Church Street pavement to a point also coinciding closely with point 9. In view of this and the differing construction between the wall at points 5 & 6 and that at point 8 the inclination is to believe that the eastern wall lies beneath that part of the garden that was not uncovered during the 1998 excavations – but what was the wall beneath the conservatory?

The age of the Chantry House has generally thought to have been 16th century but the cellar mentioned above has a tablet in it dated 1776 and is surely most unlikely to have been dug out beneath an existing building. Perhaps it was commemorating the year of its refurbishment – Henry Cheal in his book on Shoreham considered the cellar to date from the late 17th or early 18th century. Ages of old flint walls are notoriously difficult to identify and this type of flint, rubble and lime mortar construction was, for example, still being used in Shoreham into Victorian times. Bricks were a little easier to identify by their changing sizes over the centuries although there were often regional variations. The bricks discovered in this excavation had no frogs which is consistent with those produced before Victorian times and their thickness (two inches) suggest 16th century for the brick pier in the outbuilding (3). The broken bricks found alongside the west wall (A-A with B-B on the wall section drawings) were recorded as being one and three quarter to two inches thick but these could have been specially made paving or floor bricks. The two and a half inch bricks making up the brick sluice channel (4) and those of two and one eighth inches found on the top of the excavated wall at point A-A are consistent with 17th to 18th century measurements.

Most of the artefacts were discovered where the foundations for the garage were dug out (1 on the plan). Unsurprisingly, there were a good number of animal bones and oyster shells, the latter of which had doubtless been readily available to Shoreham townsfolk over many years – these could have been discarded at any period from mediaeval to Victorian, possibly including detritus from meals of the oyster merchant’s family that it is known lived at number 19 in the 1860’s.

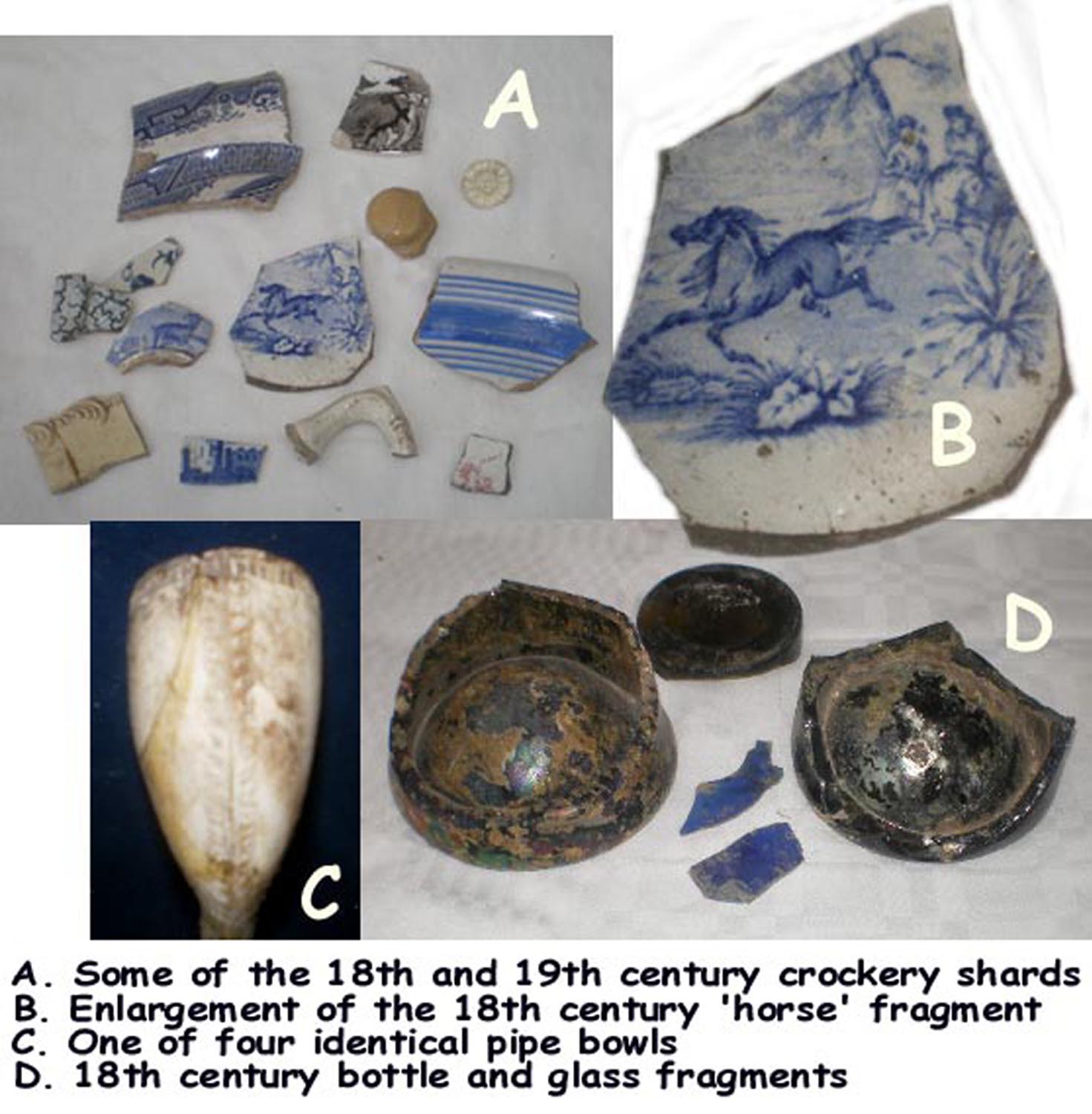

Broken, decorated crockery shards were predominant, most dating from the 18th (including one particularly attractive piece from a delicately made small bowl that portrays a galloping horse) and 19th centuries. Broken clay roof tiles with peg holes were found and thick, dark glass bottle bases again from the 18th century.

Broken, decorated crockery shards were predominant, most dating from the 18th (including one particularly attractive piece from a delicately made small bowl that portrays a galloping horse) and 19th centuries. Broken clay roof tiles with peg holes were found and thick, dark glass bottle bases again from the 18th century.

Clay pipe stems were numerous but only four 19th century unbroken, spurless pipe bowls. These have a distinctive oak leaf pattern with moulded milling around the rim and very many similar varieties of this are found in Sussex. Some pipes of this pattern were produced in the Pipe Passage kiln at Lewes between 1830 and 1880 and from 1862 were also sold through Harrington & Sons of Queens Road in Brighton.

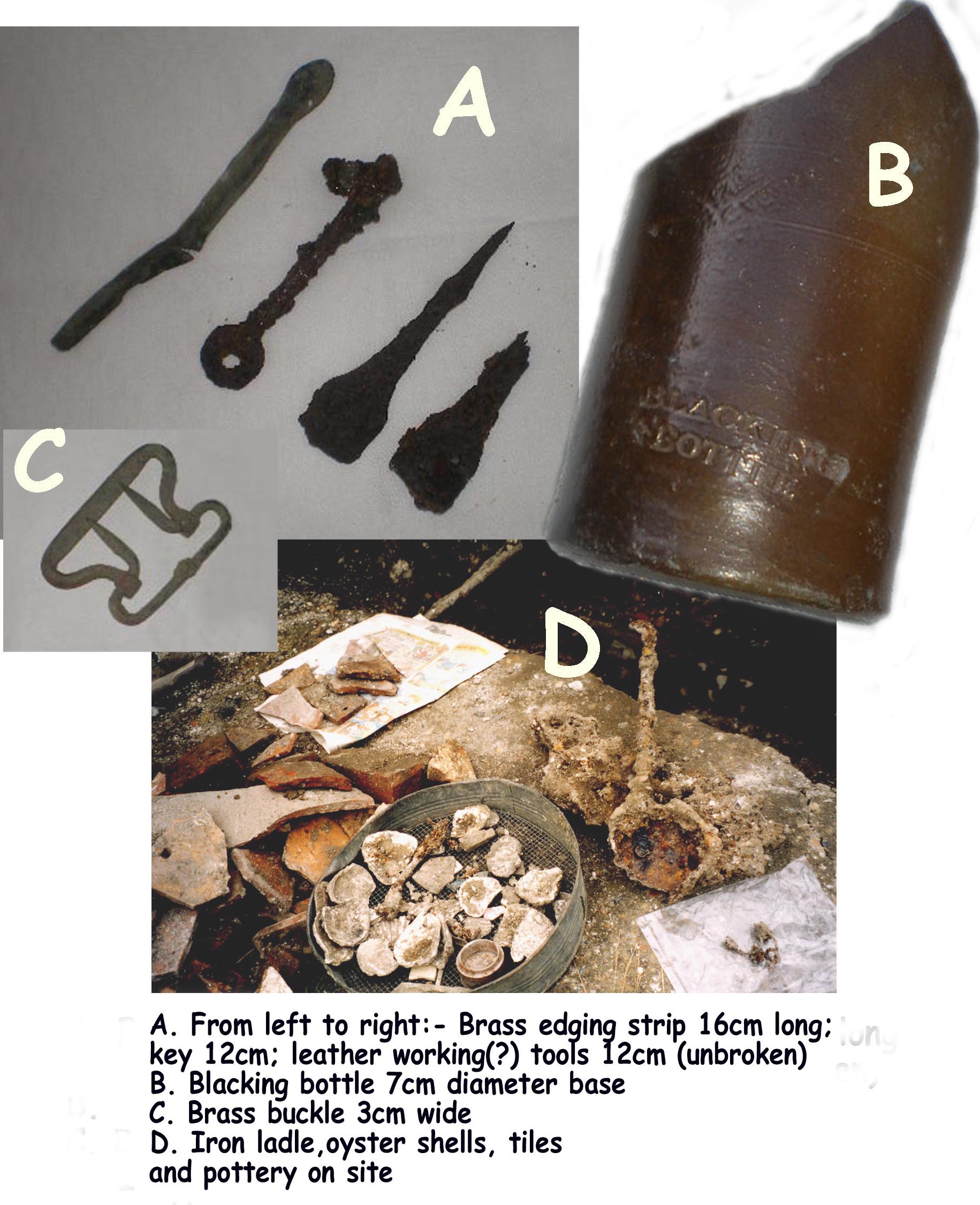

Among the metal artefacts is a brass strip edging for a box or furniture, an iron key and two tools one of which obviously once had a wooden handle. The latter may have been paring chisels for leatherwork or perhaps files from the stables where a broken stoneware jar with the impressed words ‘Blacking Bottle’ was also found. This contained an oil based dye preparation for blacking leather reins, belts and harnesses.

Among the metal artefacts is a brass strip edging for a box or furniture, an iron key and two tools one of which obviously once had a wooden handle. The latter may have been paring chisels for leatherwork or perhaps files from the stables where a broken stoneware jar with the impressed words ‘Blacking Bottle’ was also found. This contained an oil based dye preparation for blacking leather reins, belts and harnesses.

Such bottles or jars had wide necks and were manufactured in large quantities throughout the 19th century although this particular example is likely to date from before the 1850’s when the stables were demolished. A large iron ladle and chain were also discovered fused together in one lump by rust. A small brass buckle with two prongs was probably used on a small leather or material belt – perhaps for breeches or even braces. Two – prong buckles had already appeared by the 18th century and this particular design was still in use in Victorian times.

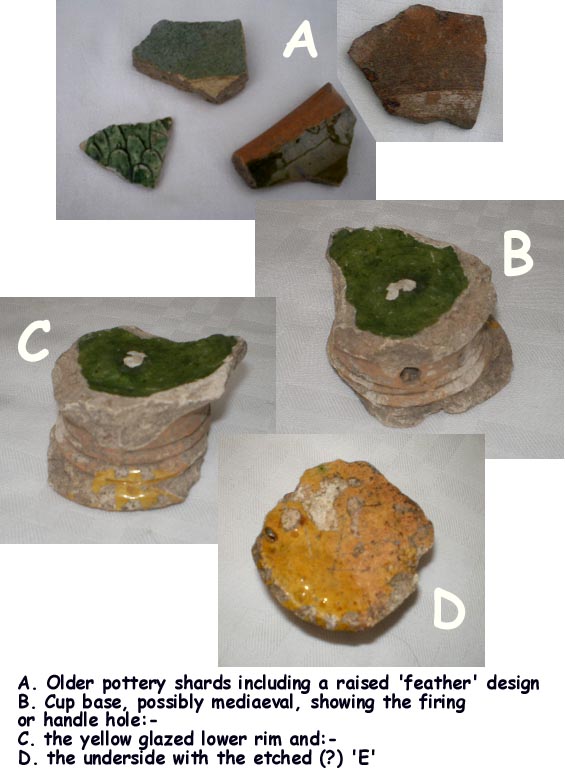

The older pottery fragments include one partially coloured white piece and some green glazed. A number of these are early post-mediaeval including imported German stoneware of the 16th and 17th centuries as well as local earthenware.

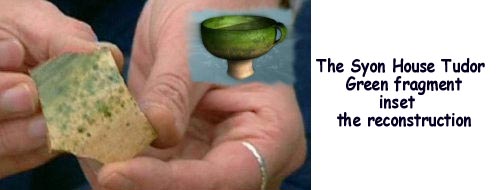

One of these latter pieces is of particular interest. It was probably once the base or pedestal foot of a chafing dish (used at the table to keep the food warm in well to do households and even then only occasionally when needed ). It is of fine textured, white/buff coloured pottery and about 4 –5 cm in diameter. It has a bright green glaze on what was the inside of the vessel and a yellow glaze on the lower rim that continues underneath the base. This lower part includes two rings moulded into it and just above them is a hole which was perhaps inserted to help the heat to reach the inside of the pedestal during firing.

The underside is fairly scratched but it is perhaps not too fanciful to make out an ‘E’ scored into it.

The chafing dish remnant is probably Tudor Green or Border ware (a good quality pottery which was made on the Surrey/Hampshire border from the end of the 14th century to about 1700). The Shoreham piece is possibly mid 16th to 17th century.

Finds of mediaeval vessels with pedestal feet are not particularly plentiful but one comparative example can be seen from the 2004 excavations at Syon House in London (above). Here a shard from the rim of a bowl of Tudor Green ware is also shown in reconstructed form, which clearly shows a ‘foot’, or pedestal not unlike the Shoreham one.

The shallow curve at the broken top of the Shoreham pedestal suggests that a similar wide-bodied bowl surmounted it and, like the Syon House example, could not have been very stable and therefore not particularly practical.

All finds are now with the Marlipins Museum

Roger Bateman

Shoreham

November 2008

Reference material:-

The 1782 Survey of New Shoreham – R.Bateman 2008 (a)

New Shoreham Houses, Owners & Residents 1782 to 1920 – R.Bateman 2008 (a)

Vault at 21 Church Street – R.Bateman 2002

The Story of Shoreham – Henry Cheal 1921

Sussex Clay Tobacco Pipes and the Pipemakers – D.R.Atkinson F.S.A

Medieval Sussex Pottery – K.J.Barton M.Phil, F.S.A, F.M.A

– with special thanks to Simon Stevens, Senior Field Officer, Archaeology South East for advice on the old Chantry House walls and Luke Barber, Research Officer, Sussex Archaeological Society for identification of the finds.

(a) in Worthing & Shoreham Libraries

My gt x grandmother Mary Ann Tiltman (nee Atherfold and previously married to William King, lived in Church Street in 1861. John kennet Tiltman her husband – a mariner – was the cousin of Stavers Hessell Tiltman who designed the Shoreham swing bridge. I thought you might find that interesting. Most of the Tiltmans were coastguards in the 1800’s all round the south coast. Brigadier John Hessell Tiltman was a famous cyptograher at Bletchley Park and Hannah Tiltman, who married Frederick Marley, is the great grandmother of Bob Marley. I hope to come visit Shoreham again this summer, it’s a fascinating part of my history and your site is wonderful. Best Wishes Allie Stewart

Many thanks Allie – as you probably know mention of the Tiltmans appears in our History of Church Street and your information is now part of this history record too!