During the 1950’s cycle rides to Bramber castle were a regular outing for us kids but mostly via the Coombes/Botolphs route. It was far more interesting that way with its winding road and steep hills, each hard climb being rewarded with an exhilarating race down the other side – this in the days when there was little traffic about, particularly on that road.

We didn’t seem to use the Steyning Road on the east side of the river so much but when we did it was something of a strange experience. Even some distance before the cement works itself the surrounding trees and bushes were completely covered in a surreal whitish‐grey deposit that was spread by ash and fallout from the works chimneys. Stopping over at the works we would scrounge any fossils that the workers found which were usually the more common fossils such as sea urchins (we knew them as ‘Crown of Thorns’) and the like but any of the more unusual ones were kept back from us kids by the workers as they commanded good prices from collectors.

On one occasion they let us look inside the huge building that housed the rotary kilns. What appeared to be two massive pipes high above us extended along the whole length of the building from which came a continuous rumbling noise. The burning process, we were told, involved ground coal being blown in to the kiln and ignited – when the chalk and clay slurry was burnt the resultant clinker was passed on to another chamber containing large metal balls that crushed it then on through other chambers that held progressively smaller balls to gradually grind the cement down to a fine powder at the far end.

The site was never a fashionable or popular one with the locals and I lost whatever interest that I may have had in it until learning of the venue of one particular Shoreham cargo vessel:‐ On Sunday the 7th April 1861 an incoming sailing brig docked on the quayside at the copper works in Llanelli. The vessel was the Shoreham registered, 450 tonne ‘Hero’ built at Messrs. J. May and T. Thwaites’ Kingston shipyard in 1857. George Vinall the master was a Shoreham born man as were two of the nine crew, able seaman Edward Poole and 15 year‐ old ordinary seaman William Churchill.

What was the purpose of the voyage and what was its cargo? Perhaps the answer lay at the Llanelli works where the copper was smelted from the ore using chalk or lime as a flux. Sussex chalk had long been quarried then burnt in kilns to manufacture lime for agricultural and building use added to which Shoreham already had its own supply close at hand.

Known to many as Shoreham Cement Works the site is actually midway between Upper Beeding village and Shoreham town alongside the River Adur. A chalk pit existed from at least 1725 and probably long before. Lime burning had been carried out throughout the county for many hundreds of years but generally on a small scale by farms for their own use and the need for sufficient supplies of coal and clay in the larger scale processes meant that lack of adequate transportation made this impossible until the industrial revolution. Coal and clay was then shipped in to Shoreham and onwards upriver in barges to the quarry kilns. By 1814 a large and successful trade in lime existed there which was carried upriver for use on the land and almost certainly downriver as well to Shoreham and beyond as a constituent for lime mortar.

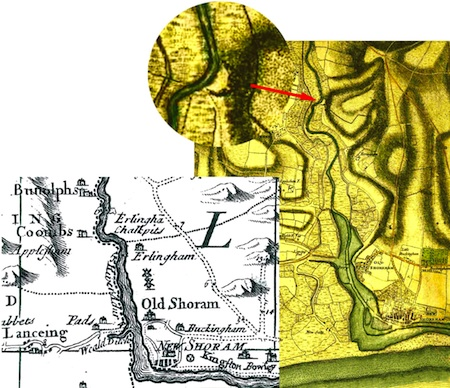

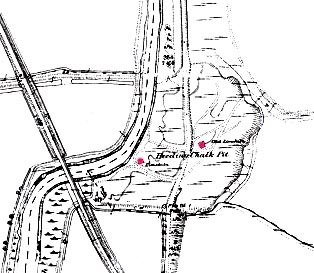

The lime was processed in kilns that were sited on the excavated land between the quarry and the river. The quarry itself can just be made out on the Yeakell & Gardner map of 1780 and although it is not precise it (the quarry) appears not to be much smaller than the one shown in 1879. During the 18th century the road to Steyning from Shoreham ran above the valley along the Downs with another from Lancing on the west side of the river. It wasn’t until the 19th century that the road on the east side below the hills was established and cut through the quarry, perhaps influenced in part by the developing lime trade there.

The chalk was burned in the kilns, probably brick built although no drawings of them survive, a skilled job that required a close watch being kept on the progress of the burning. The burning chalk turned to lime and would take many hours, sometimes days, not only to burn to the right consistency but also to cool down. A mixture of chalk and clay was burned to make cement and in both processes the resultant clinker was ground down to a powder‐like constituency to make it useable as lime to spread and work into the soil on the land and as cement to enable it to be workable when mixed with water for building work.

During the 19th century demand for cement as a more durable construction material increased. Even the town of Shoreham had its own ‘cement house’ and ‘cement mill’ at this time that ground lime clinker from the quarry – one run by George Parker in the 1830’s at King’s Arms Fields (on The Ham), the other owned by Thomas Clayton from at least 1827 to 1871, located at Dolphin Buildings (now Coronation Green) with its own quayside on the river. There was in any case ample other wharfage along the riverside between Shoreham and Kingston for storing materials such as chalk or lime for export.

The chalk (one of a number of limestone varieties) from the hillside at Beeding had long been recognized as being of a particularly good quality for use as lime and cement and this attracted the attention of those seeking to make profit from the industry. During the last part of the 19th century ownership of the works went through a flurry of changes. Following the formation of the Beeding Cement Co. by 1882, H. R. Lewis and Co., then described as limeburners and coal merchants, are recorded as owners by 1895 only to be themselves bought out a few years later by the Sussex Portland Cement Co. of Newhaven – this in turn was taken over in 1912 by British Portland Cement Manufacturers.

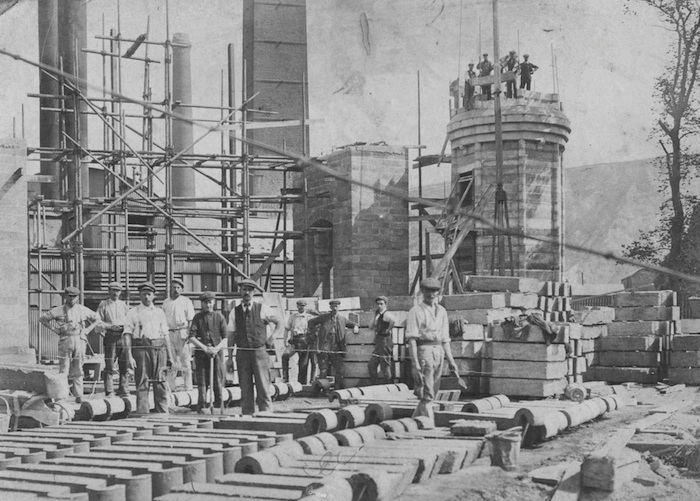

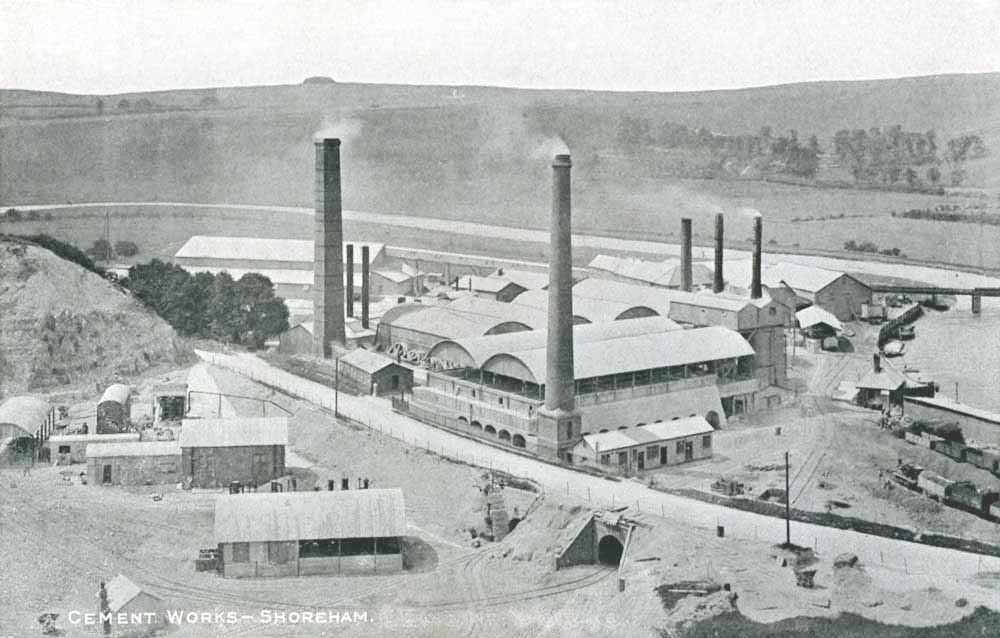

The early years of the twentieth century saw the works grow considerably in size when new buildings and chimneys were built on the west side of the road. As the cliff face was gradually ground back and further from the kilns a tramway was used to convey the chalk for processing – the trucks being pushed by man‐power or rather boy‐power if Edward Terry the 13 year‐old trolley boy employed in 1901 was normal practice.

In planning the plant’s expansion and development the Sussex Portland Cement Company directors had the foresight to research the latest machinery and processes from all over the world. It was soon realized that Denmark at that time had just completed a similar plant and the knowledge gained there was secured for Shoreham by employing the services of those Danish nationals who had worked on it (one Danishman noted as a ‘Cement Expert’ was still working for the company in 1911 – he and his family were accommodated in the Dacre Gardens houses nearby).

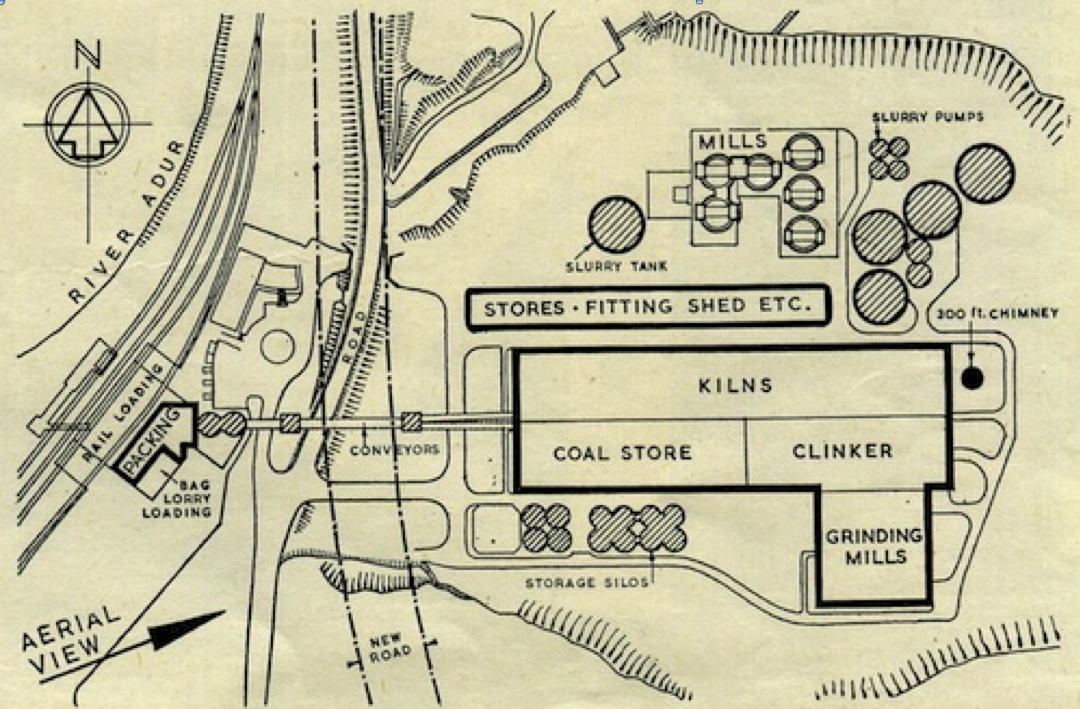

The whole site was powered by gas and electricity and a gas making plant was installed together with a new washing plant, wet mill and 250 hp gas engine to drive it. A 100 hp gas engine drove the coal grinding/drying plant for the rotary kilns, a 400 hp engine for wet and dry mills and a 60 hp Parson’s steam turbine and two compound condensing engines, all three to power the electric plant. There were fourteen chamber kilns each producing 30 tons of clinker per week but two, more efficient German Schneider kilns were purchased that each turned out 100 tons per week. American designed rotary kilns enabled complete manufacture of cement in two and a half hours compared with ten days or more using the traditional methods.

They had their own fleet of barges to receive coal, coke and clay and despatch the lime and cement. Another means of conveyance was utilized when the railway sidings on the works site were laid down to enable faster and more economical transportation of cement and materials. Two stores were erected and incoming raw material/outgoing cement was loaded/offloaded using a steam crane. With an efficient gang of men this enabled 260 tons to be loaded in one hour.

As cement production grew a nearer source of clay was discovered during the start of the 20th century at Horton that was purchased by the cement works, dug out then transported down river in barges to the works. This was later pumped in slurry form from Horton in a large pipe ‐ the resultant clay pit west of the road just before it enters Small Dole is nowadays used as an infill site.

As a result of all this activity output increased from around 5,200 tons in 1897 to 41,600 a year by 1902. The growth in business required more workers and to provide their accommodation work on Dacre Gardens (the terrace of houses just north of the cement works) began around 1901 when 28 works employees are recorded as living there with their families in the 14 properties that had been built then – some employees were from the same family but accommodation would have been somewhat cramped where two families shared the same house – 14 in one instance but this was not that unusual for those times.

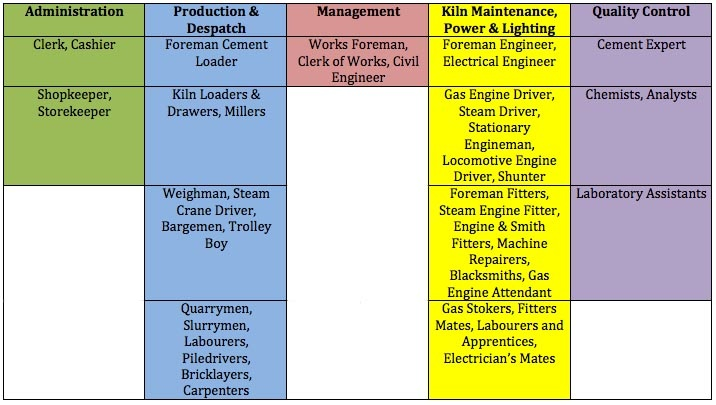

Alongside the terraced houses was a semi-detached dwelling called Dacre Villas that in 1911 housed William Ollerenshaw the Electrical Engineer, Alfred Shelbourne the Foreman Fitter and their families. The man in charge of the plant, Thomas Dow the works foreman, was given a house that overlooked the whole site. The 1911 census tells us the occupations of all the residents in the 40 or so dwellings that had now been completed. In a labour intensive environment during the first few years of building and expansion it is perhaps not surprising that the majority of them were manual workers – 36 from Dacre Gardens alone. There were many other employees who continued to travel to the works from their houses in Steyning, Henfield, Bramber and Small Dole, nevertheless, the 84 employees listed does give us a rough idea of the structure of the plant’s workforce and of the work involved:-

With the outbreak of war the need for cement became even more neccesary and production continued unabated. Despite the works being an obvious target surrounded as it was by open countryside in the Adur Valley, it did not receive much attention from enemy aircraft except, that is, on just one occasion.

At 2.55am on the 29th September 1940 a group of what is estimated to have been four German bombers attacked the works dropping a total of 16 high explosive bombs. Six of these fell on the Shoreham/Horsham branch railway line, two failed to detonate; three hit the factory itself of which one was unexploded; one fell in the factory grounds and failed to explode; one hit the Steyning Road and another five impacted on the river bank and adjacent fields.

A member of the Shoreham Home Guard by the name of Bazen who also worked at the Cement Works witnessed the bombing of the railway line and realising that a goods train was due ran down the line waving a lamp and managed to stop it.

The bomb crater in the road and the danger from the unexploded bombs meant that traffic to Steyning had to be diverted via the road on the west side of the river. Both up and down lines of the railway track were damaged, goods trucks were derailed and the factory-loading shed was demolished. Electric cables were damaged and telephone wires brought down but otherwise there were no casualties. Despite all this, after a very short time the road/rail repairs were completed and the unexploded bombs defused; the factory’s machinery was undamaged and maximum output capacity soon resumed.

Post-War Development

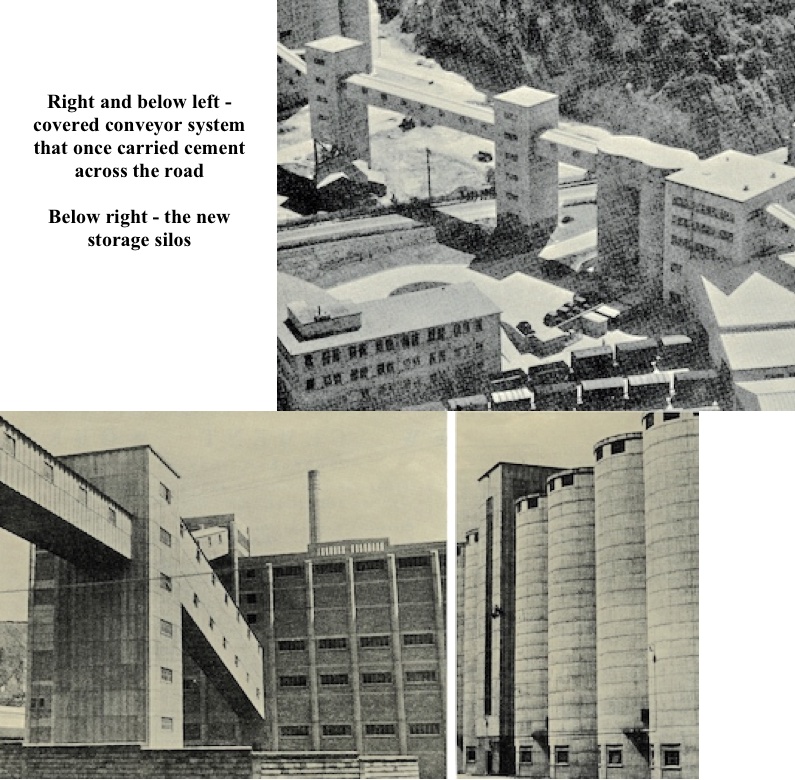

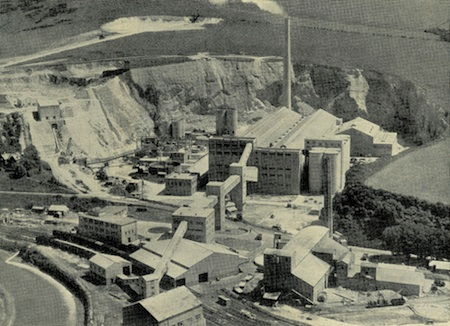

Under its later name of ‘Blue Circle’ the plant was completely rebuilt from 1948 to 1950 mainly on the cleared ground east of the road. Considered at that time to be state of the art Shoreham was the first to use the latest Vickers Armsrong kilns (these included the rotary kilns I had seen as a lad). One of the earlier kilns was retained to supplement the others but was labour intensive, expensive to run and shut down in1967. The Vickers Armstrong kilns, whilst highly successful and much copied originally were converted to filter cake feed in 1983 with a filter press. As it turned out though, this arrangement was ultimately found to limit production due to its high dust loss and was a factor largely due for the plant’s closure.

All the new buildings in the plant were made of pre-cast concrete blocks. In addition the conveyors and supporting towers were clad in asbestos cement sheet and the claim at the time was that the effect of all this made the presence of chalk dust virtually unnoticeable.

The kilns are 350 ft long by 10 ft in diameter (107m x 3m). Slurry was fed into them then pulverized coal blown in and ignited to burn the slurry at 2,500 degrees farenheit (1,370 centigrade). The resultant red-hot clinker was then dropped into open-ended cooling tubes that carried the air upwards to prevent dust escaping into the building. It may have been an effective means of controlling interior dust but perhaps this was the main cause of the pollution to the surrounding countryside.

During the 20th century Shoreham cement has been used in huge quantities for many major construction projects all over the UK, as well as becoming the most commonly seen cement bag on building sites – those of us that built our own garden paths, walls, garages and house extensions inevitably used the bags with the Portland Cement Company’s Blue Circle logo purchased from the local builder’s merchant or store.

During the 20th century Shoreham cement has been used in huge quantities for many major construction projects all over the UK, as well as becoming the most commonly seen cement bag on building sites – those of us that built our own garden paths, walls, garages and house extensions inevitably used the bags with the Portland Cement Company’s Blue Circle logo purchased from the local builder’s merchant or store.

The plant employed 250 personnel in 1968 that rose to 330 by 1981. After achieving a production rate of 250,000 tons of cement a year at its zenith (and perhaps surprisingly was still producing lime as well in 1971) during which it ate away a whole hillside, the works finally closed down in 1991.

Nature restored the foliage of the countryside around it to a healthy green in a surprisingly short time. How had the flora and fauna survived that choking dust? Somehow it had and the once busy and imposing industrial relic from an age when there was no statutory requirement to return the site to its natural state now stands slowly crumbling, ugly and vandalized.

Roger Bateman

Shoreham June 2012

(Revised 2015)

Sources:‐

British History On Line

Formation of the Sussex Cement Company (1902 newspaper article)

‘Shoreham & Southwick Bombings and Other Incidents During WW2’ by Roger Bateman

The Architect & Building News 23rd August 1951

Cement Kilns – Dylan Moore 2011

Census Returns 1901 & 1911

Detail from Richard Budgen’s map of Sussex 1725 and Yeakell & Gardner map 1780

Detail from Ordnance Survey map 1872 showing lime kiln sites

Sussex Archaeological Society image no. 96.2871 (Marlipins Collection) of early 1900’s development and 89.1319 of moored barges

All other images from ‘The Architect & Building News’ and the author’s own collection.

So interesting

My great grandfather – Henry Carter (known as Hard Hat Henry) used to walk to and from the cement works every day from Steyning.

I also recall visiting the cement works from Steyning Secondary Modern School when I was 15/16 years old as part of a programme to familiarise teenagers with the world of work. The workings and images of the rotary kilns and the conveyer belt system remain with me some 50 odd years later.

I found this very interesting, I remember being shown around the works and in the kiln sheds.

My father was a driver at the cement works from 1956 – 1972, driving a bulk tanker. My mother also worked there as a telephonist / receptionist in the late 60’s and early 70’s. I can remember the kids Christmas parties and pantomime trips provided by the works, happy days.

My wife was the telephonist at the beginning of 60’s and used to really enjoy the job.

Many years later, after the closure all the ladies who worked there during the 60’s got together and used to go out once a month for lunch etc.

The husbands called them The Cement Bags as a fun nick-name

Sadly now in 2018 there are only two of the original six still with us.

Lovely story but sad all the same. With a distinctive surname like yours John would you be related to Shoreham’s 1920’s police Superintendent T.W. Bubb?

My mother Millecent was the daughter of Alfred Shelbourne mentioned in the article!

My Grand Father A Caddy worked at the Shoreham Cement Works I believe during WWII through to 1954 when we then imigrated to Australia. He lived in Upper Beeding. My Father W Blows worked on the railways in Steyning. I remember my Grand father telling me that one day he forgot his hard hat so had to go back to get it. He was very lucky as the man he was working with was killed in a cave in. So if he had not forgot his hard hat he would also have been gone.Anyway just wondering if any one knew him or my father.

Afraid i dont, however your stroy is meaningful and impactful. He sounded like a lucky man that day, strange how life works sometimes.

My grandfather Bert Compton worked at the cement works from just before WW1 and just after WW2. He was a labourer and told me they unloaded clay from barges by wheelbarrows. They were paid piecework by barrow load and the company sometimes reduced the rate. He joined the Union. He lost the top of his finger in one of the tipper trucks he pushed. He become the drivers mate on the steam lorry, a Centinal, feeding the fire box. He rode up from Shoreham every day and was machine gunned by a German bomber. He kept a job all during the depression, was transferred briefly to Isle of Wight which he hated. They’d kept his job open for him when he returned from the army in WW1. In the late 40s he left to be boiler man at Southlands Hospital.

My husband worked there from 1987 to when it finally closed. When production halted he (Peter Hall) along with Nicholas Standing were the only two remaining employees and they both managed the depot. Prior to this Pete had been an engineer on the repair & maintenance side.