Stories of early flying at Shoreham 1910 – 1918 including personal experiences from pilots and spectators

In the early days the airfield was much smaller, situated in a tight corner on the north side of the railway bridge at the west end where it meets the river. The area is part of the flood plain and was then still soft, marsh-like ground that was partially dried by the use of ditches to drain the water into the main, boundary ditch. One of these was halfway along the main take-off area but was boarded over and marked with a red flag. The other ditches though still did not allow much space for aircraft to lift off and were the cause of a number of mishaps.

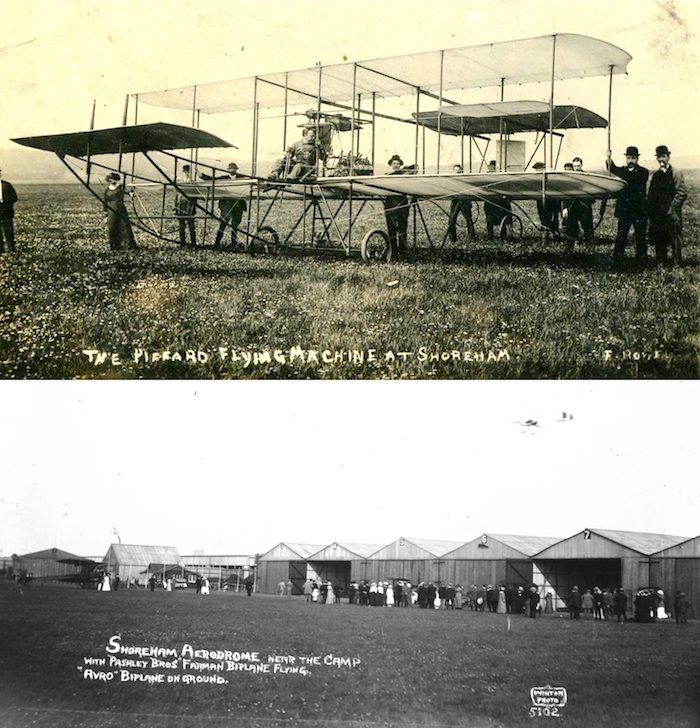

One Shoreham resident of the time recalled, “A very large field near our river was made into an aerodrome and the first aeroplane took off, or rather jumped off. The machine was a queer contraption with open cockpit, and as the field contained many ditches, it ran along the ground and nose-dived into each one before rising a few feet into the air.”

This must have been referring to the early attempts at flight in 1910 by Harold Hume Piffard, an ex-Lancing College pupil who designed and built his own plane. To begin with he only managed a series of hops before eventually achieving a ‘proper’ flight on July 10th that year but was never able to turn the aircraft and such a manoeuvre always ended in mishap.

Flying then was not easy. Those early aircraft were flimsy canvas wood and wire machines usually propelled by underpowered engines. Provided the wind was not too strong they could leave the ground at under 40 mph with a top speed of about 50 mph so there was a 10 mph margin. Flying below this speed caused a stall, spin or slip and above it resulted in engine overheat or stress to the structure causing wires or wood within the aircraft to snap.

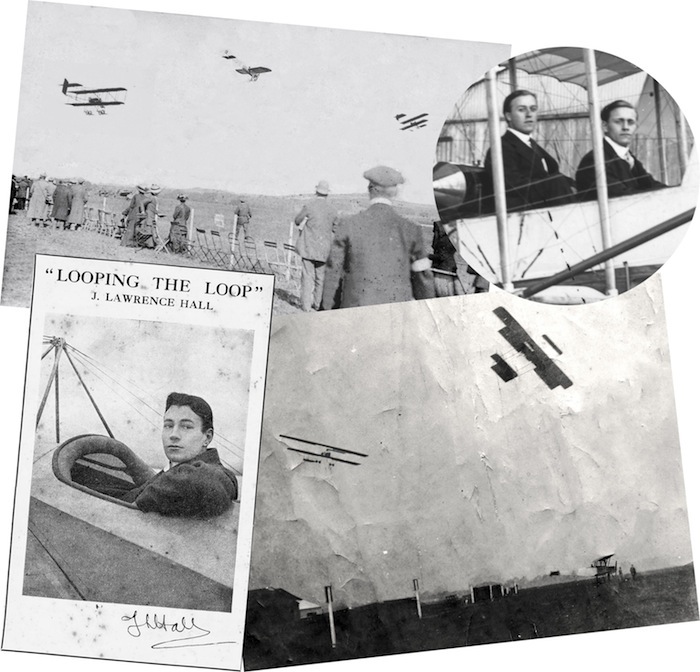

Gradually other pilots and planes started to use Shoreham more, notably Oscar Morison in 1911, a well known Shoreham flier followed by Grahame Gilmour and others. The airfield soon became established as a major flying centre with air shows featuring aircraft ‘looping the loop,’ altitude record attempts, bomb dropping, illuminated night flying and both long and short distance races that involved pilots from all over Europe.

For short distance races the airfield course was a little over one and three quarter miles long marked out by pylons. The last pylon before the home straight was positioned so that competing aircraft had to bank steeply near the enclosures to provide spectators with an advantageous view of the pilots at their controls. The air show of Saturday 11th July 1914 featured J.L. Hall in his Avro 502 biplane, Eric Pashley flying the Pashley brothers’ own aircraft they had designed and built, Cecil Pashley flew an old Henry Farman biplane (Eric and Cecil ran their own flying school at Shoreham), Jack Alcock flying a Maurice Farman (Alcock was, with Arthur Whitten-Brown, later to become famous for crossing the Atlantic in a Vickers Vimy), W.H. Elliott and G.J. Lusted both in the older Henry Farman biplanes.

Hall put his Avro into a steep climb and upon reaching 2,200 feet dived the aircraft and after dropping several hundred feet pulled the stick back to demonstrate a perfect loop. For the races there were a number of heats and competitors were handicapped, starting in staggered fashion with the older, slower planes having a three-minute start on the fastest (Hall’s Avro 502). Eric Pashley, Hall and Alcock qualified for the final that Eric won convincingly by 1 minute and 3 seconds and with it the Brighton Cup and £70 prize money. On other occasions longer distance races involved Shoreham as the finish from start points like Hendon and part of the route for major marathons such as the European Circuit.

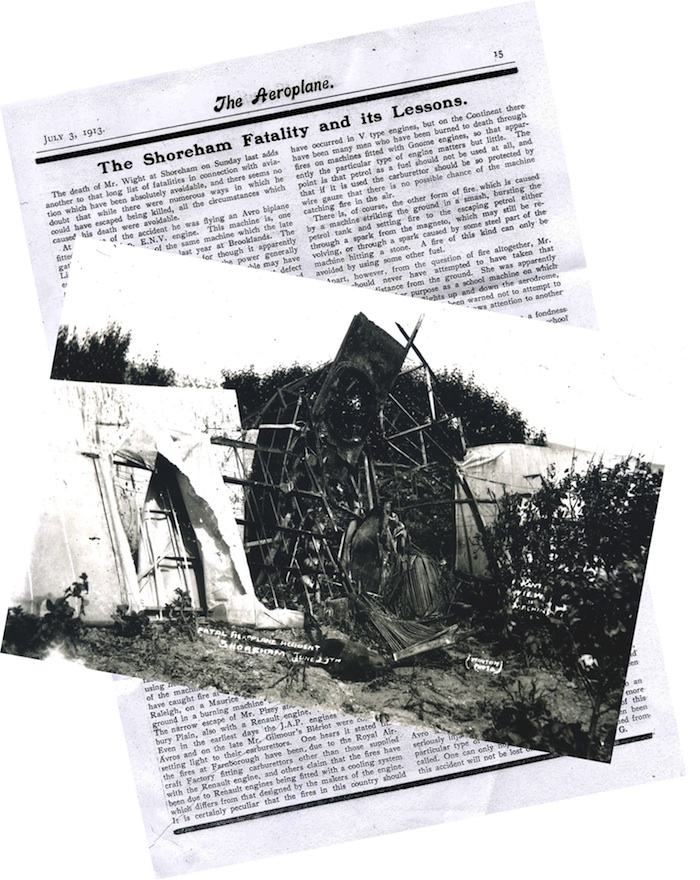

Flying training was provided by such as the Chanter Flying School and, of course, the Pashley brothers later joined by B.H. England and even the Avro Company’s own flying school. In those days aircraft design and flying safety was much less of a concern than now and even machines that were not capable of turning safely in flight were still used for learning short, straight ‘hops.’ Inevitably there were accidents but none fatal, that is not until 29th June 1913.

Avro Flying School’s trainee pilot Richard Norman Wight was flying an Avro 502 biplane when it stalled and crashed into the garden of New Salts Farm. Wight survived the impact but was trapped in the wreckage. Tragically, the machine caught fire before he could be cut free and he was seriously burned before dying at the Sussex County Hospital later that day. This fatality, the first in an Avro, was widely reported in the national press but it was editor Charles G. Grey’s article in ‘The Aeroplane’ magazine of 3rd July that used the accident to emphasise the dangers of flying then. This particular Avro 502 was fitted with an E.N.V. engine that Grey considered to be underpowered and because of this was only intended for use within the airfield boundaries. Criticising the high fire risk of aircraft, aircraft engines generally and the underpowered engine (even hinting at Avro’s possible faulty tuning), Grey also blamed the pilot for, apparently, ignoring Avro’s instructions not to go beyond the confines of the airfield.

One particular problem was experienced when taxi-ing was still confined by the ditches to the small southeast corner and prevailing winds required a short take off over the river. When reaching a point above the water the air conditions there altered causing pockets that made the aircraft ‘bump’ in mid flight. At this stage the aircraft, already in a slow and cumbersome nose-up attitude, reacted by either the tail or nose coming up or one wing dropping – unless the pilot reacted instantly to correct this the machine either stalled, went into a dive or side-slipped into the river.

Despite repeated instructions always to fasten safety belts one trainee forgot (apparently there were no supervised pre-flight checks then) so that when he reached the river and experienced the turbulent ‘bump’ he just managed to prevent being thrown out by hanging on to the joystick. By pure luck this did not cause the aircraft to stall or dive and the pilot pulled himself back into the seat. Eventually the ditches were filled in enabling the use of a larger part of the airfield with a longer, more controlled take off and helped reduce the accidents.

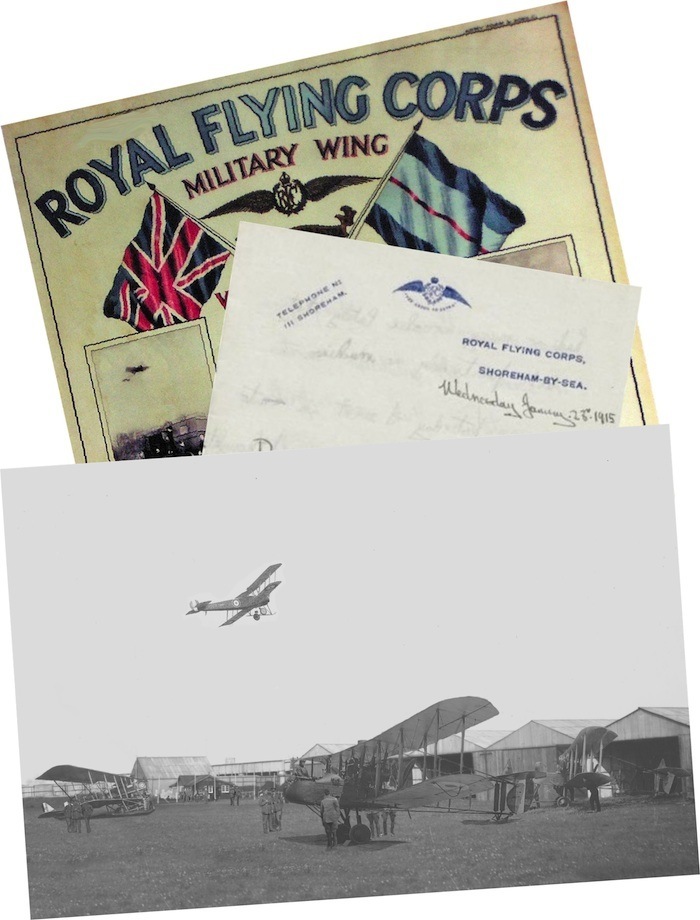

In 1915 the Royal Flying Corp’s No. 3 Reserve Squadron (later renamed No.3 Training Squadron) had taken over the airfield – with their arrival the number of flights increased considerably and inevitably so did the flying accidents. In fact one new trainee pilot wrote home complaining “I’ve had no flying as we’ve had so many crashes lately that we’ve practically run out of machines!” This is borne out by the same pilot’s report that there were only three aeroplanes available at one stage, one of them was an old Avro, an ex. school machine that was very difficult to fly but once mastered was said to “enable one to fly anything straight off!” In fact this lack of machines and instructors, too many pupils and weather so awful during the early months that many would be trainee pilots gave up waiting and opted to return to the army regiments from whence they had come.

The total number of aircraft varied from time to time as did the different types. Initially equipped with a few ageing Maurice Farman Longhorns and Shorthorns that were eventually increased to twelve, other types followed such as F.E.2d’s, Avro 504k’s etc., and, in the latter years of the war, even one or two examples of up to date fighters to prepare the fledgling pilots for the front line machines. With the RFC suffering huge losses in France however, and the pressures on the training units to produce replacements the duration of pilot training was woefully short. There was a six-week basic tuition period requiring a minimum of three hours dual flying and three solo which was short enough in itself but this was not always met – some trainees at Shoreham received as little as 90 minutes instruction (one had only thirty minutes) before their first solo flight which all contributed heavily to the number of accidents, fatal and otherwise at this time. Hitherto there had only been one flying fatality at Shoreham – there were eight from 1915 to 1919 as detailed at the end of this article.

Training flights were inevitably very short, usually between five to fifteen minutes long, below 1,000 feet and always within sight of the airfield. Allowing for the inexperience of the newer pilots and the cumbersome and unwieldy Farman Shorthorns, training flights for them were not permitted when the wind speed exceeded 5 mph. Consequently, flying opportunities tended to be restricted to the calmer early morning and evening weather parts of the day and often not at all.

On aircraft with dual controls pupils could lightly rest their hands and feet on the joystick and pedals then note the responses of the machine in flight to the instructor’s movements. Until the introduction of the ‘Gosport Tube’ as a means of communication between pupil and instructor shouting was about the only way to converse and even then was almost impossible to hear above the noise of the wind and engine. Instructors would often bang the pilot on the shoulder or kick his seat to draw his attention then use sign language but Shoreham instructor Lt. Russell favoured the use of notes that he passed to the pupil in the front seat!

A typical daily schedule for Shoreham trainees was:-

7 – 8.30 am. Early morning flying was available ‘if required’

8.30 am Breakfast

9 am – 12 noon. Lectures. Flying ‘if required’

1 pm. Lunch

2 pm – 4 pm. Lectures. Flying ‘if required’

4.15 pm Tea.

7 pm. Dinner

The mention of ‘flying if required’ probably depended on how much tuition any individual was considered to need rather than what he actually wanted but in reality it depended more on just how many machines were available as well as the weather conditions. During periods such as when only three aircraft were airworthy opportunities for practical flying experience must have been infrequent.

Wind direction in those days was indicated by a ‘T’ shaped piece of wood and canvas that was pivoted in the ground with the cross piece facing the wind. One particularly gusty day a learner pilot in a Maurice Farman Longhorn was coming in to land but forgot to check the ‘T’ which had changed direction so that the aircraft came in much faster than was intended. The machine hit the ground and bounced back up but to complete the landing would have resulted in the machine colliding with the hangars so the pilot opened the throttle. Luckily the engine responded immediately (a little unusually for those early engines) and he just managed to clear the hangars.

The undercarriage was however badly damaged and a normal landing in that condition would inevitably have resulted in the wheel supports collapsing, the nose digging into the ground at speed and the engine (which was behind the pilot in that particular aircraft) smashing into the hapless pilot. Deciding on a very slow ‘pancake’ landing where the aircraft is flown increasingly slowly a few feet above the ground until it flops down to a sudden stop the trainee made his approach. Too slow at more than a few feet up and the aircraft would stall, too fast and the undercarriage would collapse – both situations probably resulting in the engine breaking from its mountings and killing the pilot. On this occasion the ‘pancake’ was reasonably successful if somewhat too high and the pilot was slammed onto the ground still in his cockpit but badly injuring his legs.

Apart from the initial hops and short flights in and around the airfield longer trips for trainees followed, one example in 1915 recorded a round trip of 80 to 85 miles from Shoreham to Horsham, Midhurst, Chichester, Littlehampton and back to Shoreham.

Minor mishaps were frequent, sometimes due to carelessness as much as mechanical failure as evidenced on another flight in January that year. Captain F. W. Smith had arrived to take part in setting up the RFC at Shoreham and on one flight as a passenger accompanied a Lt. Lewis. Flying first to Lewes then back to Littlehampton they turned around for the return leg but at 3,500 feet over Goring the engine stopped. Without power the aircraft began to descend but it restarted (presumably the wind resistance continued turning the propeller) but at 800 feet up over the sea it stopped again. With some difficulty they managed landfall and a landed in a small field to find that the petrol tank was empty – something that should have been checked before take off!

In the summer of 1915 Lt. Frank Gooden, an experienced test pilot for the Royal Aircraft Factory visited Shoreham flying a new BE2c around the country on a series of test flights. He left with a civilian passenger and took off south westerly towards the sheds, climbing steeply against a strong headwind then steered west. Some way beyond the sheds at about 150 feet up the steady roar of the engine at full throttle was interrupted by a stuttering noise as it lost power and the nose of the BE dropped. Keeping into the wind for an emergency landing onto the Salts Farm fields with the lack of engine power would at least have enabled a short landing albeit on rough ground and may have been able to restrict any damage to a broken undercarriage or propeller. Perhaps he was not prepared to risk even that to the new machine and, despite being an experienced flyer, Gooden then made the major mistake of turning back.

Adeptly maintaining a flat course in an effort to maintain height he turned downwind until he was back over the sheds then began turning sharply into the wind again hoping to land on the flat ground alongside. Even as he banked though he was stalling and the BE’s nose dropped like a stone just clearing the shed roof but smashed into the ground alongside. Both men were motionless as a menacing glimmer of flame beneath the wreckage erupted with a roar into a massive explosion from the ruptured petrol tank. Gooden revived in time to release his safety belt and leap through the flames but his passenger although still moving did not follow. Extinguishers had no effect on a fire fed by 30 gallons of fuel and would be rescuers helplessly witnessed the appalling scene as the passenger roasted alive before their eyes (1).

In July of 1915, well into his initial dual controlled training, Lt. Duncan Grinnell-Milne was hoping for another opportunity to fly with his instructor that morning only to be told to prepare for his first solo flight. Panic took over – he knew he’d progressed well but this was too soon! He still did not know enough about flying besides which it was cold, he hadn’t had his breakfast, hadn’t said his prayers and now felt as if he were about to face a firing squad!

He climbed into aircraft numbered 2965, one of Shoreham’s Farman Longhorns. The mechanics looked round for the instructor then back at the pilot now realizing the pupil was going solo. The plane’s nacelle felt very empty with just him in it. ‘Switch off?’ asked the mechanic. ‘Switch off’ he replied. ‘Contact’ called the mechanic. Perhaps the engine wouldn’t start he thought hopefully as the first turn of the propeller failed to ignite but with the second turn it burst into life as he reduced throttle then looked through the mass of wood and wire of the wings to see the mechanics grinning wickedly at his obvious trepidation.

Farmans were powered by an eight cylinder, air cooled, small but generally reliable (for those days) engine which when running slowly made a sound that Milne described as being ‘like two ticking clocks on a marble mantelpiece.’ They also had a large tea-tray of a front aileron on booms projecting forward from the aircraft that gave it its’ name ‘Longhorn,’ handlebar-like controls and ‘harmonium’ foot pedals. Opening up the throttle the ticking of the engine became more strident as he frantically tried to remember all that he had been taught – hold the handlebar between thumb and forefinger, feet gently on the pedals, ease back at the right speed then keep that forward elevator on the horizon – and before he knew it he was airborne at four hundred feet heading towards Worthing. After only three minutes the pier passed beneath his feet reminding him he must turn back – never make a level turn, put the nose down but not too much and very, very gently turn the handlebars slightly, keep an eye on the speed gauge, keep aware of the danger of stalling, spinning, overheating the engine, putting too much strain on the aircraft – how on earth did these things manage to stay aloft? As he turned the bungalows on Shoreham Beach came into sight – straighten the rudder, level off, speed gauge 53mph, too fast, bring the nose up.

With the first turn completed he flew back over the airfield, even chancing to look down to notice a crowd of his fellow pupils eagerly watching his progress or possible lack of it. Distracted for that moment he was reminded of his task with a sudden jolt in his stomach as he noticed that his speed now was only thirty-eight and dropping – put the nose forward very gently and soon Brighton appeared before him. Making his second turn he headed back into the wind then over Shoreham town put the nose down and throttled back to glide toward the airfield still keeping an eye to the speed gauge now reading a satisfactory forty-two mph.

Of all the manoeuvres they went through in training it was the landing he feared most. This was when the majority of accidents happened and aspiring pilots ended up with wings sprouting from between their shoulder blades instead of the RFC pilot’s ‘wings’ they coveted. Despite the calming ticking of the engine and reassuring steady rush of air in the wires would he be able to flatten out and judge the right height and moment of landing? The Longhorn glided serenely across the river (no mention by the pilot of air turbulence from the river on this occasion) and safely cleared the airfield’s east bank. At what he thought to be the right height he tentatively eased back the handlebars and gently turned the pedals to keep the aircraft into the wind. The sigh of the wind in the wires fell and the front elevator rose. Forgetting, in the stress of the moment, the sounds and reaction of aircraft when he had been with the instructor panic returned as a rumbling noise began from beneath the machine followed by a scraping from the rear. The speed gauge and altimeter registered zero – he was down.

Shortly after going solo and being posted to Gosport, Grinnell-Milne was tasked with flying back to Shoreham to deliver an urgent letter for a senior officer there. He was piloting a Caudron – a little up-market from the older types of Farman machines then used at Shoreham and was looking forward to showing this off to the former fellow pupils from his time that were still being taught there. He reached Shoreham and dived towards the airfield managing even to ‘buzz’ the engine as he turned in a gentle spiral for the benefit of his audience, straightened out and achieved a perfect landing. In addition to the gathering of trainees he noticed a group of officers that included the senior officer he was after. As a final flourish to complete his impressive entrance he taxied quickly to a halt near them, sprang efficiently out of the cockpit and, in front of everyone, tripped on the Caudron’s protruding control wires and fell flat on his face!

Known RFC fatalities at Shoreham

Richard Norman Wight, 24, trainee pilot killed when his Avro 500 biplane stalled, crashed into the garden of New Salts Farm and caught fire. 29th June 1913.

William F. N. Sharpe, Lt, Number 3 Training Squadron. Sharpe, a Canadian, became his country’s first aviation fatality during his first solo flight on 4th February 1915 when his Maurice Farman side-slipped and crashed north of the Sussex Pad.

In 1916 the unknown passenger of a B.E.2c was killed when his pilot, Lt Frank Gooden, made the classic mistake of turning back to the airport when the engine failed and the aircraft stalled just short of the airfield.

Wyndham Trevor Harries, 24, 2nd Lt., Number 3 Training Squadron. Killed 21st August 1917 when his aircraft crashed at Ecclesden Farm, Angmering after engine failure.

Thompson Calder Kinkead, 24, 2nd Lt., Number 3 Training Squadron. Killed in a Maurice Farman aircraft that crashed at Ham Bridge, Worthing after engine failure 3rd September 1917.

Aime Antoine Leger, 21, Lt., Number 3 Training Squadron. Killed 4th September 1917 after his aircraft’s exhaust manifold fouled the propeller and crashed in the sea.

Vivian Spence Edmunds, 18, 2nd Lt., Killed 6th September 1917 when his aircraft side-slipped and crashed.

Cecil George Douglas Mousir, 18, Cadet. Number 3 Training Squadron. Died 23rd February 1918 – circumstances of death unknown.

Albert Debrisay Carter, 28, Major, DSO and Bar, Croix de Guerre, Commanding Officer of 2 Squadron. Killed May 22nd, 1919 after the wing folded of a Fokker DVII when he was carrying out aerobatics over Lancing College.

(1) This tragic episode must have haunted Gooden for the remainder of his short life but his experience and flying ability was such that he was nevertheless retained as the Royal Aircraft Factory’s test pilot going on to carry out much dangerous and important work on many experimental aircraft. He finally lost his own life at the young age of 26 at Farnborough in 1917 whilst testing a prototype SE5 aircraft.

Roger Bateman

Shoreham

February 2013

Sources:-

The Shoreham Fatality and its Lessons – 3rd July 1913 article in ‘The Aeroplane’ by Charles G. Grey, editor

‘Shoreham’s WW1 Fatalities’ by Brian Roote.

The Shoreham reminiscences of Cynthia Bacon’s mother

‘Flying at Shoreham’ article in ‘Flight’ magazine 7th July 1914

‘Shoreham Airport, Sussex’ by Tim Webb

‘A Pilot’s War 1915 –1918’ extracts from the diary of Major F.W. Smith in the RFC

‘Wind in the Wires’ by Duncan W. Grinnell-Milne

‘My Life’ by Oswald Mosley

‘A Royal Flying Corps Trainee’ by A. Bryant

Photos:-

View to the Airfield 1913, Piffard’s aircraft, Airfield 1913, Morison/Gilmour and Roedean Race, Wight’s crashed aircraft all from Sussex Archaeological Society Collection (Marlipins Archives).

No.3 Reserve Squadron NCO’s – Ashley Roote

Shoreham Airfield 1915, RFC poster, 1911/1914 races at Shoreham – author’s collection

J.L. Hall postcard – Bartlett Collection

(All information from the publications mentioned have been rewritten in the compiler’s own words)