The reminiscences of Bessie Bailey and her daughter Peggy.

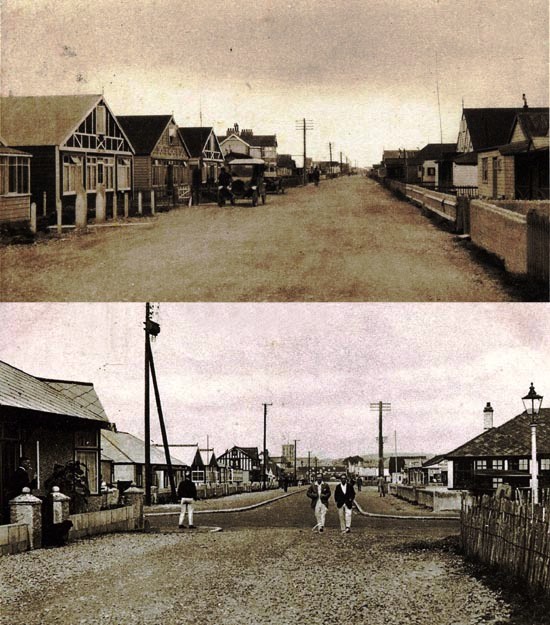

Foreword: – In the early 1920’s much of the Beach was still undeveloped and the bungalows and houses that were there were spread along the seafront with little or nothing behind except in Ferry Road. There was no electricity, gas, or mains drainage; water was brought from the mainland in a large zinc cistern and sold at 2p a bucket to supplement the rainwater collected in storage tanks. The houses were given bizarre names rather than numbers.

Brick built residences did exist but there were many cheaply constructed bungalows made entirely of wood, often built around redundant railway carriages that were carried across the river at low tide on wagons pulled by a team of horses. Soon however, the appeal of life on the Beach was such that more new bungalows began to be built and the foot bridge was constructed to provide easier access to residents. Many of the newcomers were theatrical or film actors and actresses, possibly influenced in the first instance by the film studios near the Beach church – there were famous people too such as Sir Malcolm Campbell. However, the majority were increasingly temporary residents, holidaymakers who were able to afford the cheap family breaks at the bungalows during the summer months.

There were no houseboats then – that is until the Bailey family arrived:-

Part One – Bessie Bailey

Bessie Ada Clark was born in 1896 at Tenterden in Kent at a time when buses were drawn by horses and Queen Victoria was Britain’s reigning monarch. One of her earlier memories was of the troops that included her soldier uncle returning from the Boer War to an official welcome at Tenterden town hall.

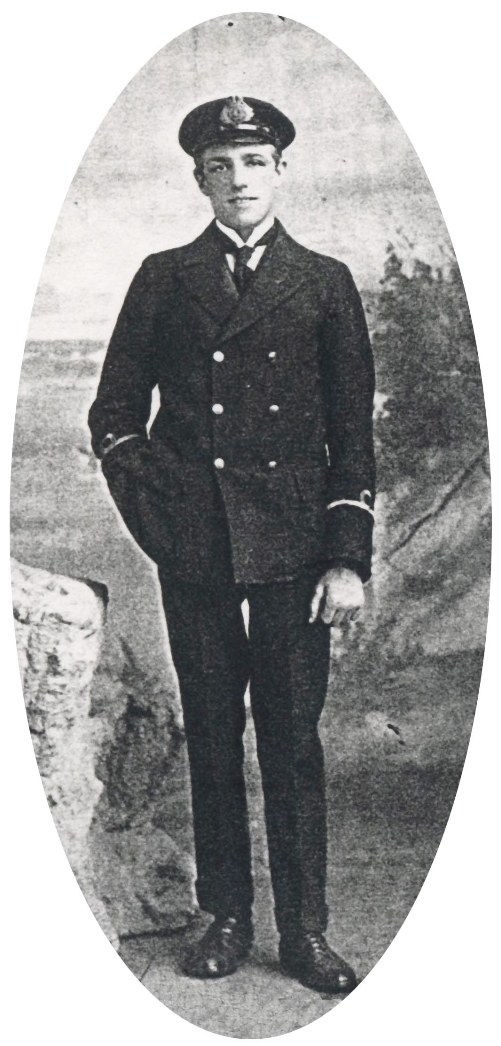

Bessie went into service at the age of 14 and after a spell in Australia with her brother sailed back to England in April 1918 when she survived the torpedoing of her ship, the RMS Tainui. Later she joined her sister Ethel, the wife of Frank Rowe photographer, postcard manufacturer and newsagent at 18 High Street, to work at their shop. It was here that the Rowes developed their photos and postcards in the cellar and Bessie would assist in the shop and during this time she met and married her husband Frederick Bailey a merchant navy officer, in 1922.

Bessie and her husband set up home on the Beach in 1926 in a converted yacht which was the first time a house boat was used over there. This was moored close by the Riverside Road and had no light or water – paraffin was used for lighting and cooking and their water tank was filled by a hose.

People living on the Beach at this time were not at all popular with those of Shoreham town because there was much drunkenness and loose living on the Beach. However, many residents lived there temporarily – actors and entertainers in between film and theatrical engagements or holidaymakers in the rented bungalows during the summer months – and it was nearly always these people that caused the problem.

The Beach then was in two sections – the east side and the west side. The east side around Ferry Road had many ‘shacky’ bungalows as well as some that were more soundly built. Some were let out to holiday makers in the summer and were empty during the winter. Others were let to people staying in the area a short time who quite often left owing their rent and other debts. Many folk though went to live on the Beach as it was a very enjoyable ‘away from it all’ free and easy life.

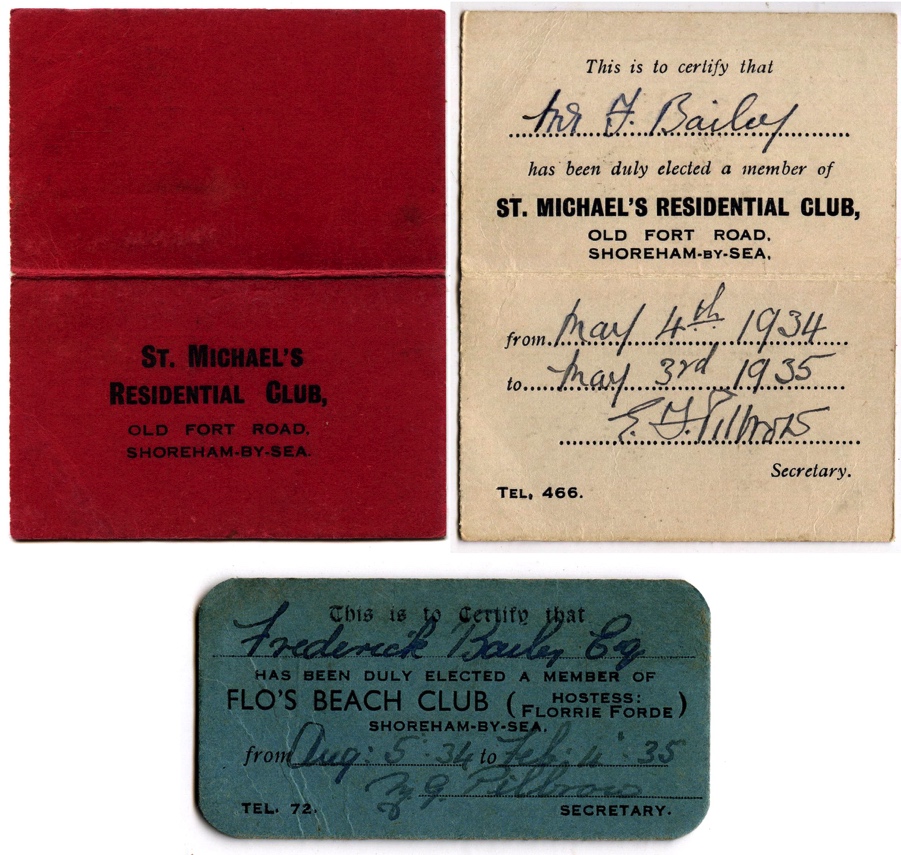

There were two clubs in Ferry Road then, one a very respectable sports club, sometimes nick-named the ‘Church Club’ and had tennis courts and other facilities such as billiards etc., This was run by a Mr. Moreton Cook of Cooks Jam Company in Shoreham. The other club called ‘Flo’s Club’ was where Atlantic Court now stands. It belonged to Florrie Ford the famous music hall entertainer and there was much drinking there but eventually both clubs disappeared during the war.

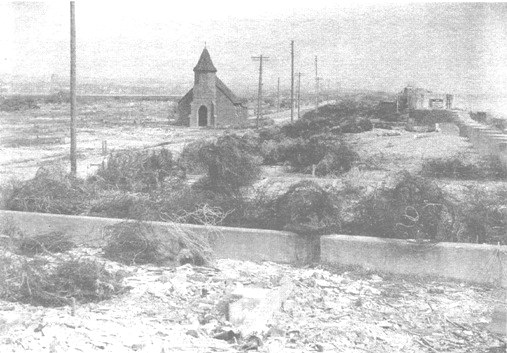

The west side of the Beach had the larger and more prosperous bungalows which were occupied by many theatrical people. This included the area around the Church of the Good Shepherd and westwards to Widewater where bungalows were often flooded and damaged by the ravages of the sea. ‘Stills’ the builders on the Beach were called upon to build a defence of strong concrete along the shore by the bungalows with steps down to the beach – all done by hand, no concrete mixers then and extremely hard work.

Life on the Beach in the early days before the footbridge was built was rather cut off especially on the east side; a ferry operated from the town but was dependent upon the tides. The ferrymen charged quite heavily at night and were most upset when the footbridge was built. Nevertheless, the bridge was welcomed by the residents and the toll was 1d each way for adults … a halfpenny for children and 1d for bikes. The halfpenny charge for children though was considered expensive particularly as they had to travel each day to and from their schools in town and after some agitation by residents the charge was discontinued altogether.

Roads on the beach then were rough, often very muddy and it was said that Beach folk always had muddy shoes and dirty windows – the latter due to the salty sea spray. There was no mains sewerage and to begin with most of us only had a bucket placed in a little hut in the garden. Buckets were emptied nightly by a man who called round with his horse and cart but eventually each bungalow had septic tanks installed.

A gas supply was laid at this time and gas meters fitted to record the amount used. Erratic payments by householders and often no payments at all led to restrictions being imposed by the gas company. A Mr. Gunn would daily ride his bike around the Beach turning on 1/-s worth of gas to those bungalows displaying a ‘G’ in their windows (whose occupants presumably had to pay on the spot).

There were a few ‘shack’ shops in Ferry Road too. One of them was Eade’s Stores whose manager was Mr.Evans, a man well known in Shoreham. This shop also had the sub-post office within it run by the even better known sub postmaster and town historian Henry Cheal.

Frank Rowe, my brother-in-law and newsagent on the corner of Church Street, used to deliver his newspapers to customers personally, trudging around the Beach from bungalow to bungalow. Fred Batten would cross the river at low tide in his milk cart and horse accompanied by his barking dog. He crossed the river diagonally from about where the Yacht Club is now and continued to do this long after the footbridge was built.

During the 1920’s the couple had two children, both daughters, but sadly Frederick Bailey died in 1936.

In August 1940 during the last war when fear of invasion was rife the beach was evacuated. Larger bungalows were blown up and smaller bungalows boarded up. Residents from the Beach were put into rented accommodation on the mainland. Bessie’s own bungalow

survived the demolitions but she was not subsequently able to return to her home until 10 years later. Bessie enjoyed a long life and eventually passed on in 1996 at the age of 100.

Part Two – Peggy Bailey

“I was born on Shoreham Beach at my Aunt’s bungalow (Ethel Rowe) called ‘Ferngarth’ in what was then the Meadway on the spot where the middle flower bed of Atlantic Court is now. My parents had the first houseboat to be moored in the river behind Tudor Mansions in Riverside Road. It was a converted ocean sailing yacht and they named it ‘Speedwell.’ My father had been in the Merchant Navy and created a happy home out of that yacht. Both my parents loved their time there as it provided a very carefree life – little housework to do but cooking and washing weren’t easy as Mother only had a methylated spirit stove to heat water. No electricity, lighting was provided by paraffin lamps and a length of hose was used to fill our water tank each week.

When my sister was born my parents decided a boat was not the place to bring up children so my father built a small bungalow which he named ‘Melbourne.’ He made the tiles by hand using a press and raised a union jack flag when the roof went on. At spring tides the water used to come up to the front door when we would walk on stilts to get in and out of the bungalow – great fun!

Sadly our father died at the age of 37 and Mother had to sell the boat as she couldn’t maintain it – it used to move, almost walk in fact, from its’ berth in a gale and high tides; crockery fell from the shelves and was smashed and because the boat had moved from its’ upright position we had to sleep lop-sided until the next high tide when the boat would be hauled back into its’ berth.

Life was very carefree then; we had a dog and walked him to the Silver Sands, along Riverside Road past the Sussex Yacht Works boat builders and the chemical works. Skylarks sang, rabbits ran about, lovely gorse in bloom, blackberries and valerian were everywhere. When we reached our goal, the Silver Sands which is now behind the Harbour Club, it was great fun – the sand nearest the river was ‘sinky’ and nearer the shore was silver. We didn’t swim in the river because the tide was too fast. We also walked to Soldier’s Point and to the Fort, just the buildings there then, gorse and wild flowers – back along the north side of Old Fort Road, which did not have many bungalows along it only wild flowers and shingle, until we got to Shingle Road. We used to go to Sunday school there where a Mr. Lansdown played a pedal organ and gave us a sweet and text at the end of the service.

A regatta was held each summer which was a source of great excitement for us all and we would watch from the houseboat with friends and relatives – rowing, sailing, tug of war in the mud and pillow fight competitions on the greasy pole for which the prize for the winner was a joint of beef. We had a small boat which was eventually taken up river to Bramber. To reach it we would cycle alongside Good Friday Hill (Mill Hill) along the Steyning Road where bluebells and primroses abounded.

There were four clubs on the Beach then, nightclubs you may call the less reputable of them now: – Arthur’s Club (run by Arthur Godfrey whose son, also Arthur, was later to become the well known Shoreham artist) Riverside Club, Fort Club and Sports Club The latter was quite respectable had four tennis courts, two billiard rooms, one armed bandit machines and a ballroom. There was also the Show Boat moored near the footbridge that also provided entertainment. We had a battery wirelesses then and the battery had to be taken to the shop to be recharged every week. I remember my father having a battery wireless with headphones.

The Beach had its’ fair share of characters – there was Major Sexton, an ex. army man who walked around still dressed as if he were a soldier. ‘Meths Liz’ was another – she came from a good family and wore long flowing dresses, floppy hats and dirty plimsoles. A cigarette was always hanging from her mouth and she would walk on her tip-toes, never letting her heels touch the ground. As her name suggests she was often the worse for wear and after a night’s drinking would inevitably be found in the gutter and taken home by the milkman on his early morning rounds.

When we were older we went to the Church of the Good Shepherd and walking to it along Beach Road we would pass one house that often had its’ windows open from which we could hear Hitler’s speeches ranting out from a wireless – the lady that lived there was German and she was interned when war was declared. The organ at the church was pumped by hand and the choir came from the Grammar School. We went to Brownies originally and later the Girl Guides where we had our meetings at the church hall. Once a month we had church parade and carried the union jack flag up to the altar – our Guide leader lived at Widewater.

Talk of war was rife and people started hoarding, filling their larders with food. We were issued with gas masks and sandbags were provided if you wanted them. On September 3rd war was declared and I was with friends that day listening to Mr. Chamberlain on the wireless telling us the frightening news. I rushed home where my mother made us put our gas masks on as the siren had just sounded and she was sure we would all be gassed. Being children we had no real fear of the consequences of war and thought it all rather funny making rude raspberry noises by blowing, expelling the air out of the sides of the masks.

In the early part of the war life continued fairly much as usual except that we carried out air raid shelter drills at school and then evacuees started arriving in the town. They all came in by train and Mr. Perkins, the garage owner, opened both of his garage’s doors so that the children could walk straight from the station through to Ham Road and the Children’s Home which stood where Somerfields is now. From there the children were literally selected by people in the town who were required by wartime legislation to provide homes for them. We had an evacuee girl called Rita, a very quiet girl of nine – her brother was billeted across the road with our friends, a very streetwise Londoner – their father, a London taxi driver, came to visit and was so pleased to see she was happy here with us that he gave my sister and I half a crown, a lot of pocket money then.

There were some changes in our lives; the main one was that the school day for local children was reduced to half a day – us in the mornings and evacuees in the afternoons and, of course, we spent a lot of time in air raid shelters when the sirens went. Many of the bungalows on the Beach were, even in peacetime, empty outside of the summer months and even more so in wartime. I particularly remember one occasion after a high tide and strong gales going to church along Beach Road and seeing furniture and balconies from bungalows on the beach that had been demolished by the storm, floating out to sea.

There were two luxury yachts moored in the river near us; one was called the ‘Anzac’ at the back of the pub (today’s ‘Riverside’ pub then called the ‘Tudor’ on the corner of Riverside Road and Lower Beach Road), had a crew of five and was owned by local brewery owner Tubby Edlin; the other was named the ‘Taransay’ which was moored further along Riverside Road. Both yachts were commandeered by the Navy at the start of the war.

When Dunkirk fell we were all rather frightened and lived with our suitcases ready packed after being warned that we might have to leave our homes at short notice. Unbeknown to us Mother owned a gun at this time and if the Germans had invaded was prepared to shoot us – something we weren’t aware of until many years later. Access via the footbridge was only permitted at certain times. There used to be a curfew and we had to be home by 9 o’clock when the footbridge was closed, the middle section drawn back to prevent access and a guard posted at Kings Drive at the road entrance to the Beach. We did have a small rowing boat which mother thought she could use to row us across to the town if necessary.

We had a friend in Ferry Road who had the paper shop and she used to let us bring the comics home to read as long as we ironed them and took them back. In the same road was a tea lounge called the Pebble Cafe where we were sometimes taken as a special treat? We sat on Lloyd loom wicker chairs and were served ice cream in a glass dish on glass topped tables. Talking of Ferry Road also reminds me of the Lido that was at the beach end of it and on Sundays a small organ was pushed on to the shingle for open air church services.

In August 1940 things actually started to happen in earnest and we were given 48 hours notice to move off the Beach as the War Office thought the Germans could use the area to gain access to the town and the country beyond and use the bungalows as cover. During this time I remember a German bomber flying over us towards London. Mother managed to rent accommodation on the mainland from someone who worked at ‘Ricardo’s’, there were plenty of houses that were empty then as people were moving inland away from the threatened areas.

The army themselves actually moved us. Items of amusement were restricted to one per household so my sister and I chose our wind-up gramophone although Mother wanted her piano as well. As luck would have it the piano had to be moved as it was in the way of the necessary furniture but in being moved got stuck at the front door. A sergeant was called over and said we already had our one permitted item (the gramophone) but the soldier moving us pointed out that it had to be got out of the bungalow in order to gain access to the rest of the furniture and couldn’t be put back in – as a result Mother got her piano after all.

This was the end of my childhood and home life on the Beach. The threat of invasion decided the War Office on clearing the beach to enable a clearer view of invading troops and therefore easier defence by our soldiers and guns on the higher ground in and behind the town. Bungalows were blown up by the Army from West Beach to Ferry Road and all along the foreshore right up to the Old Fort. We could hear the detonations from where we were in the town and even when this was finished they laid mines along the beach which would occasionally explode during high tides and storms and could be heard above the noise of the wind.

Like so many others at the time, the war changed our lives forever and, of course, things were never the same after that. It was long after the war had ended before permission was given for people to return to the Beach but we did eventually manage to get back in 1951 and I have been here ever since.

Part one adapted from an interview with Bessie Bailey in July 1984, Part Two from the reminiscences and writings of Peggy McCulloch nee Bailey.

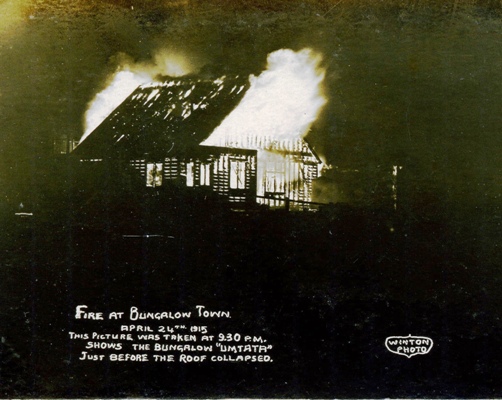

Photos from the Bailey family collection which can be viewed in its entireity.

Edited by Roger Bateman September 2009.

2017 Postscript:- The Melbourne still stands but has been sadly neglected by subsequent owners and is now partly obscured by a garage which uses the bungalow as a store. Despite the abuse of the years Melbourne somehow still manages to display its’ charm and character.

Interesting. My grndparents had a bungalow on the beach which was blown up at the start if the war. It was called Kashmir. My parents were married in 1939 at the Church of the Good Shepherd. Have a mumber of photos