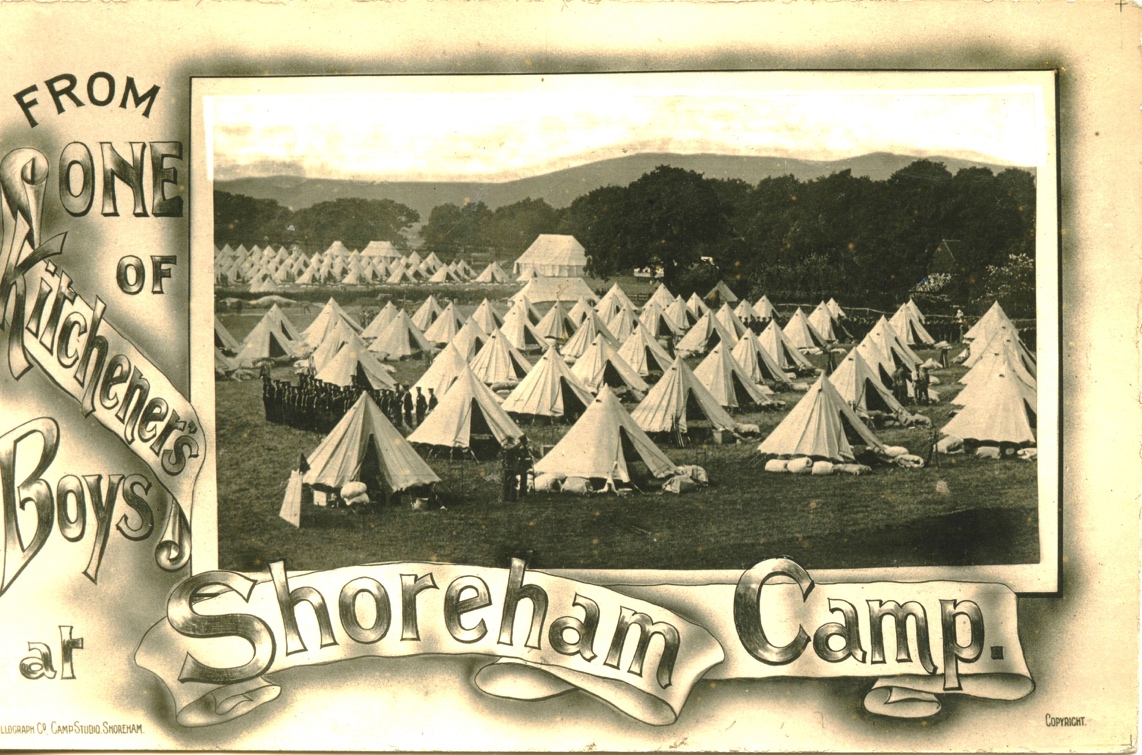

Following the commencement of hostilities Lord Kitchener was appointed Secretary of War and it was he that laid the format for the organisation of four separate armies. Shoreham with a railhead, seaport and airport in a strategic position on the south coast became the location for forming the 24th Division, part of Kitcheners Third Army or K3 as it was known..

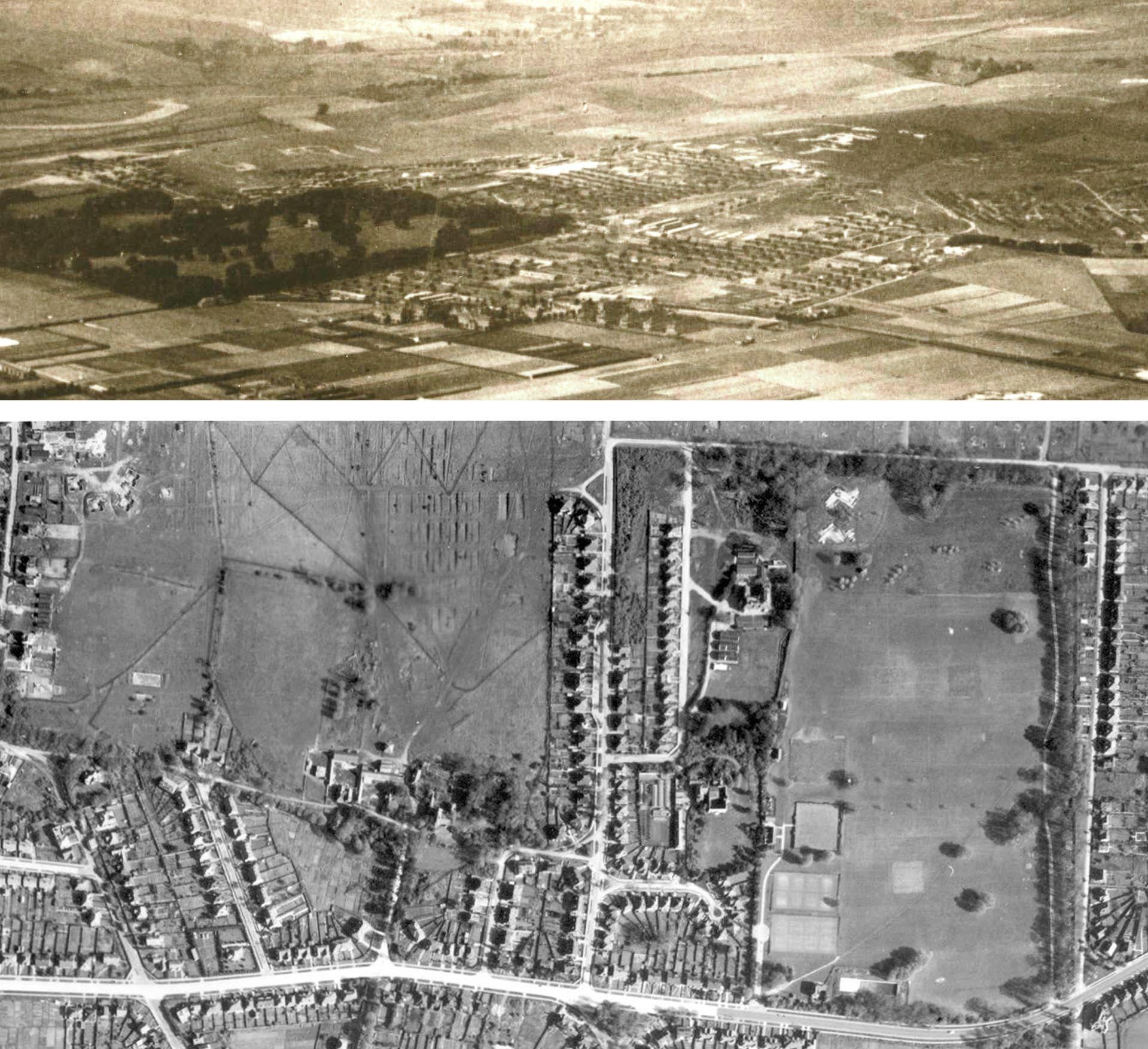

Almost before the ink was dry on the recruiting posters men started arriving by rail at Shoreham and local territorial soldiers began creating a tented camp on the Oxen Field to the north of Mill Lane. The close proximity of the railway station to the field meant that heavy equipment could more easily be hauled there. Initially, there were no instructors to train the new recruits nor uniforms or small arms. The flood of men was so great that the churches and townsfolk were needed to assist with providing temporary housing and food for them. As new recruits continued to arrive it was not long before Buckingham Park was also being used as a tented army camp with a field kitchen and latrines dug to provide a modicum of hygiene. The local Territorial soldiers were engaged to set up the spacing for tentage and supervise raw recruits by organising swimming parties on the Beach and holding basic roll calls to keep unsworn trainees busy.

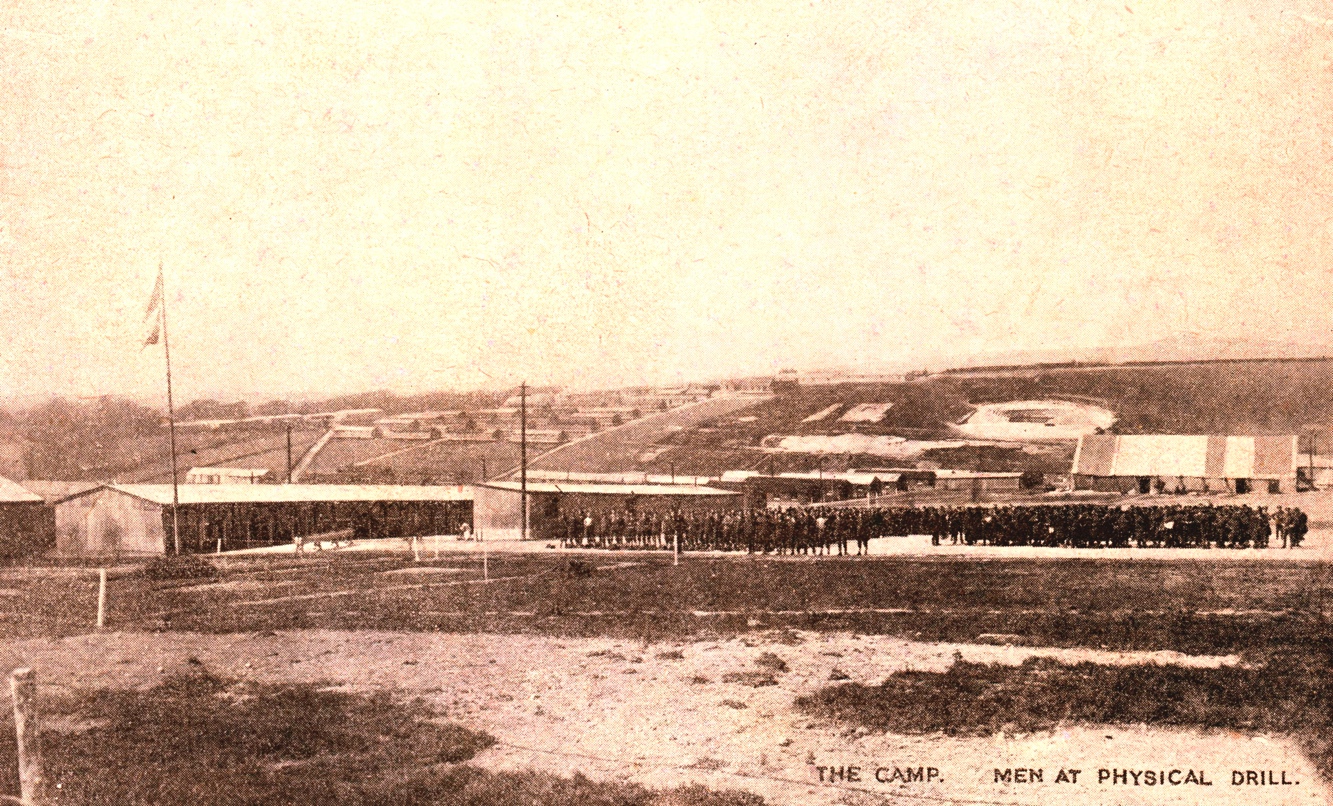

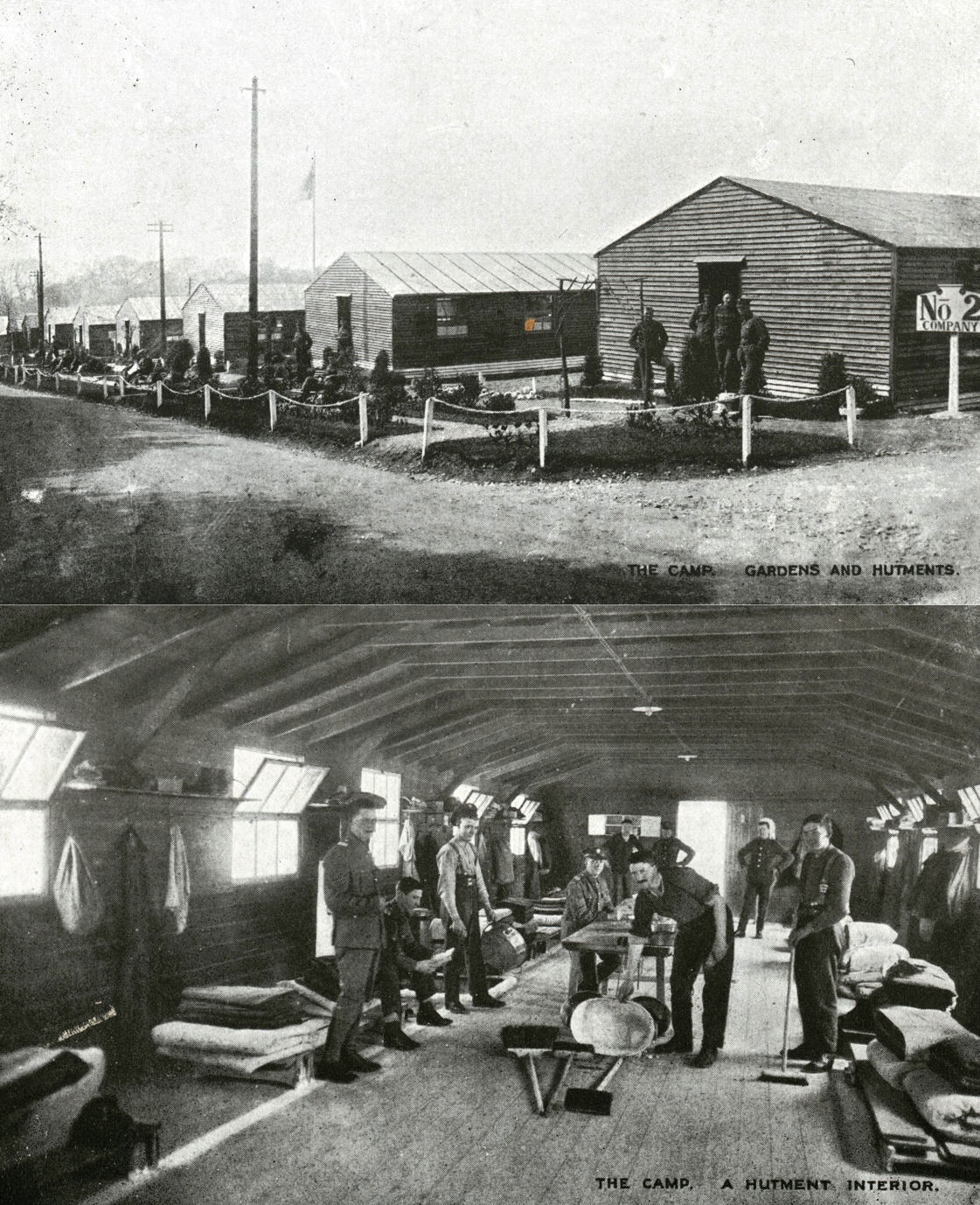

The occupation of time to prevent the onset of boredom became a priority and a large parade ground with a hard surface was set up on land at Mill Hill. The building of wooden offices to house the Headquarters Staff and Quartermasters stores were built adjacent to the square. As time progressed wooden buildings to house the Medical Officer and staff were erected and it wasn’t long before recruits were being taught basic drill and how to march in line of route. The volume of mail at Shoreham post office increased so much that eventually an army post office was opened at the Mill Hill camp. A sanitation unit was provided but as this did not include a laundry the army posted a request in the local paper with a tariff of charges asking for laundering services which was responded to by many Shoreham housewives.

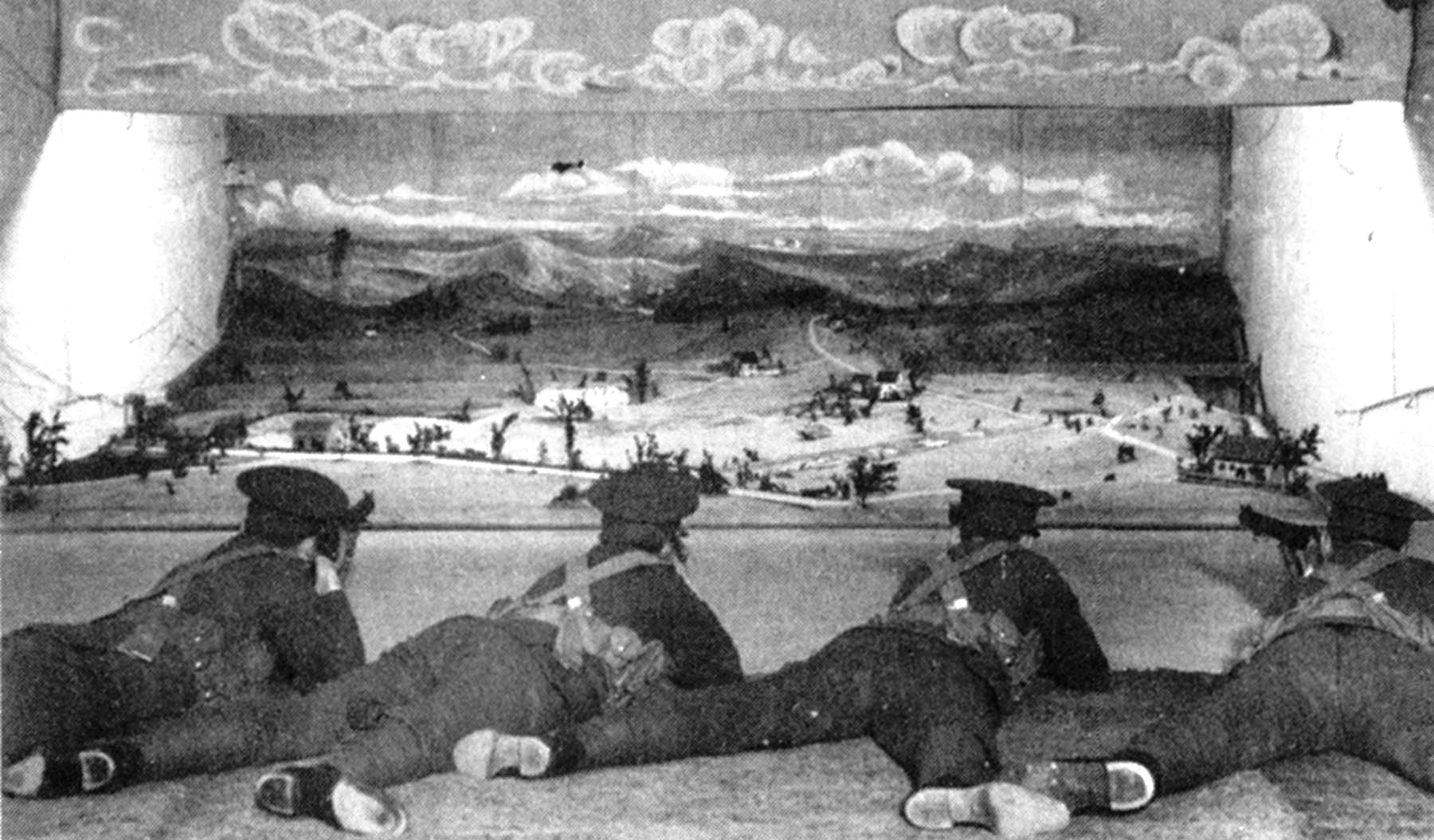

Regular servicemen returning to ‘Blighty’ from India found themselves posted to Shoreham Mill Hill in order to pass on their military skills to the new recruits. Early rifle shooting training without bullets used indoor Hill-Siffken landscape targets which were used in areas where space was restricted and to save ammunition. The ground floor of Marlipins Museum was set up with these targets as were two large greenhouses at East Worthing near to what is now Onslow Court on the sea front.

It is understood that the inflow of new recruits was so rapid that by late 1914 Mill Hill camp was almost entirely tented but around 20,000 men were still in civilian clothing. Even the gate guards had no rifles and carried just a swagger stick each. Uniforms did not arrive until May the following year and the whole Division only had two rifles that had been borrowed from the Lancing College Officer Training Corps.

Following the winter of 1914/1915 which caused huge mud slides in the camp the tents were replaced by wooden billets that accommodated 20 men each and included a Corporal who was in charge of the hut. Drill purpose rifles were issued initially and replaced later by veteran Lee Metford long single action rifles which had been in use since the Boer War. Once basic drilling skills had been learned, uniforms were issued which came complete with a kitbag and large and side packs. Working parties were organised to assist with the construction of the billets which were built by local contractors and the Army Procurement Executive.

The basis of early training was to provide discipline, the ability to take orders, security of manpower, exercise and an ‘early to bed/early to rise’ routine. The civilian population living near to the camp soon became used to the army bugle calls of ‘reveille,’ ‘cookhouse’ and ‘lights out.’ A popular day for every soldier was pay day when all ranks paraded to salute and sign for their weekly pay. This was always given to soldiers in alphabetical order of their surnames so that those with names beginning with ‘W’ often had to stand patiently for an hour or more to receive their money.

As winter turned to spring and the weather improved an outdoor rifle range was set up at distances of 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200 yards on the open downland above the camp. Army chaplains and Church Army bible readers were drafted into Shoreham to cater for the men’s spiritual needs. Canteens were built but did not then involve the NAAFI (Navy, Army & Air Force Institute) which was not founded until 1919. Red Shield Clubs run by the Salvation Army provided tea, light snacks and board games with the Young Men’s Christian Association providing similar facilities. The army did supply a ‘wet’ canteen but soldiers on basic training were confined to the camp and the partaking of alcoholic drink was strictly forbidden. Horse-drawn transport for the regular instructors though was laid on for social trips into Brighton.

After seven weeks when the initial training had been completed further instruction in field craft, route marches, the use of machine guns and trench mortars took place. The area above Buckingham Park and Slonk Hill was transformed to create a realistic battleground where trenches were dug and barbed wire laid before them. The golf clubhouse on the Downs above Southlands Hospital was commandeered to become an officer’s mess. Shoreham had then two distinct camps, Mill Hill for recruits and Slonk Hill for learning advanced soldiering. Soldiers who had elected to serve in the Corps ie the Medical Corps, Pay Corps, Artillery and Signalling left Shoreham after basic training to go on to Aldershot and other regimental depots to complete their training.

The army of 1914 was fairly self supporting providing its own facilities such as barbers and boot repairers. The Veterinary Corps manpower included veterinary surgeons, blacksmiths and facilities for kennelling dogs with men trained in grooming and feeding horses. The 24th Infantry Division was formed out of men trained at Shoreham and possessed an ammunition train comprising some 500 horses used mainly to pull artillery field gun limbers. At places like the Shoreham camp local blacksmiths were also employed in order to cope with the huge number of horses used in training.

In June 1915 rifles were eventually issued to all soldiers and the 24th Division by then comprising 35,000 men was posted to Aldershot during 19th to 23rd June where Earl Kitchener and King George subsequently inspected them. On 19th August orders were received to move to France and a few days later the Division went into action at Loos in Flanders where an appalling 4,178 casualties were incurred for little or no gain. During the period September 1915 to November 1918, the total number of casualties was put at 35,362, including those killed, missing and wounded.

Training continued at Shoreham where facilities gradually improved as the camp became a wooden town with a number of shops for the troops run by local traders such as William Winton’s stationery store and the Burfoot brothers who provided vegetable produce grown at their Middle Road nurseries. In all, five Divisions trained at the camp and left an indelible memory on the residents of the town. A memorial in the St Georges Chapel of St Mary’s church is virtually all that remains of the once huge training base that existed in Shoreham.

Gerald White, June 2010

Reference Sources:-

‘The Long Trail’ internet website www.1914-1918.net

‘Peter Jackson Cigar Merchant’ by Gilbert Frankau – although a book of fiction much is based on fact concerning the Shoreham camp.

Family reminiscences – handed down from my Shoreham forebears who had first-hand knowledge of the events at the time.

My grandfather Pte Thomas William Brown 1890-1918 from Highgate, London (SR755, 12th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers) was posted to Shoreham on joining September 1914. I have his many letters that he wrote home before going to France in August 1915. He continued writing from France until he was killed at Achilet-le-Grand, Bapaume, 23 August 1918.