1911

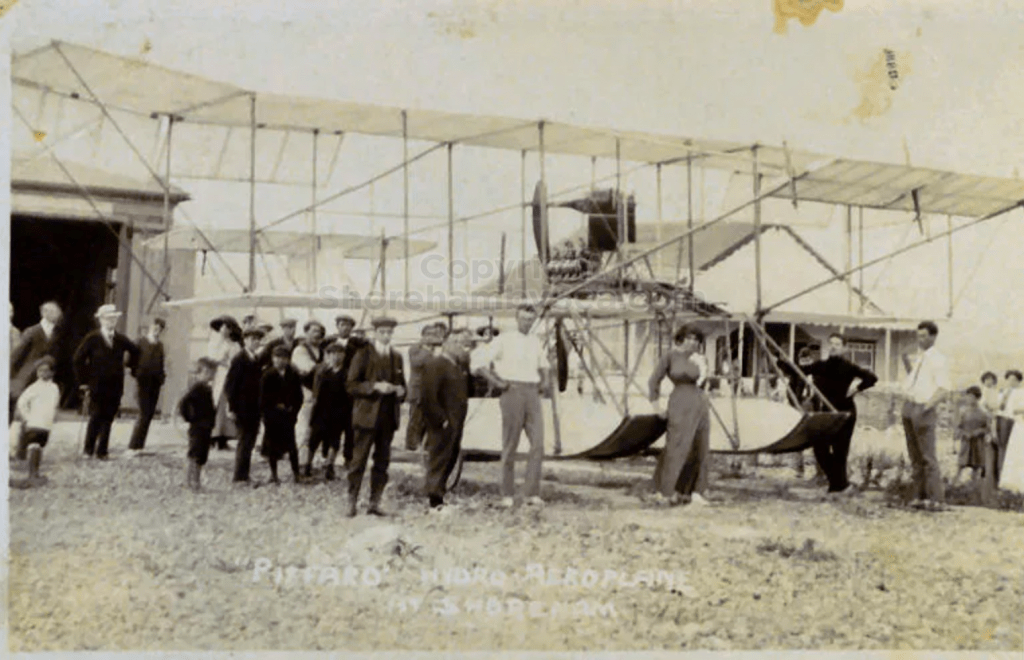

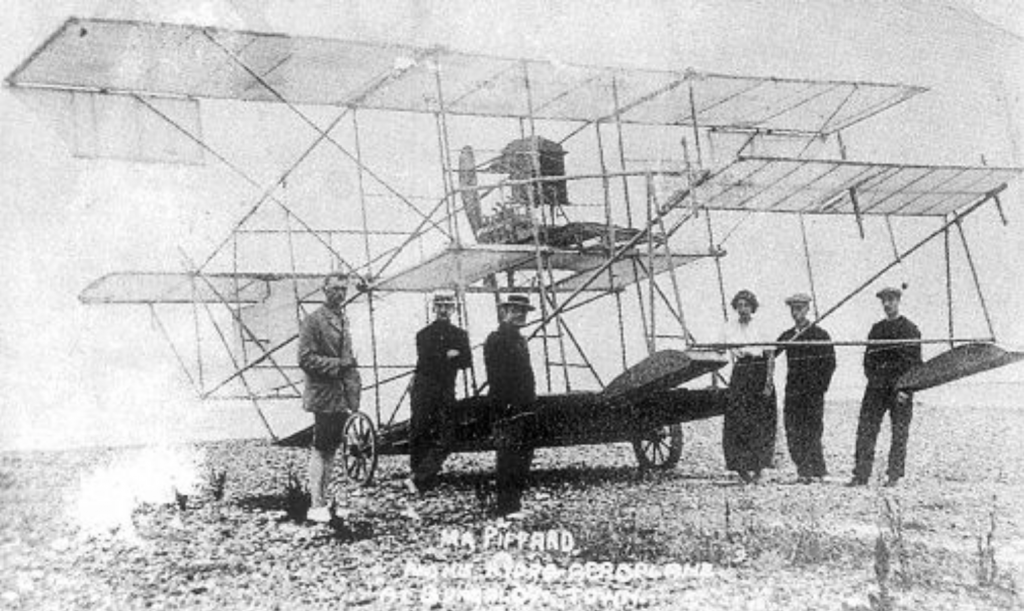

In the summer of 1911 Piff was back in Shoreham, but this time he used a large shed on the shingle peninsula known as ‘Bungalow Town’, on the beach front, near Ferry road. Thanks to fellow local history enthusiasts, Howard Porter and Roger Bateman, the bungalow has been identified as ‘Palghar’, and the shed they used to house his hydroplane, was the old Lifeboat House.

Piff’s next designs were forerunners of the seaplane, but the challenge now was to be able to ‘unstick’ from the sea. Flight magazine of 22nd July 1911 reports:-

Hydro-Aeroplane at Shoreham

“Mr Harold Piffard, who last year experimented at the Shoreham Aerodrome with an aeroplane, has now had another machine built, and this is fitted with airbags so that the experiments may be made over water. On Saturday evening Mr Piffard had it out on the sea at Shoreham for the first time, and although no flight was attempted, six people took their place on the machine and successfully tested its buoyancy. Motive power is provided by a 40-h.p. E.N.V. engine“

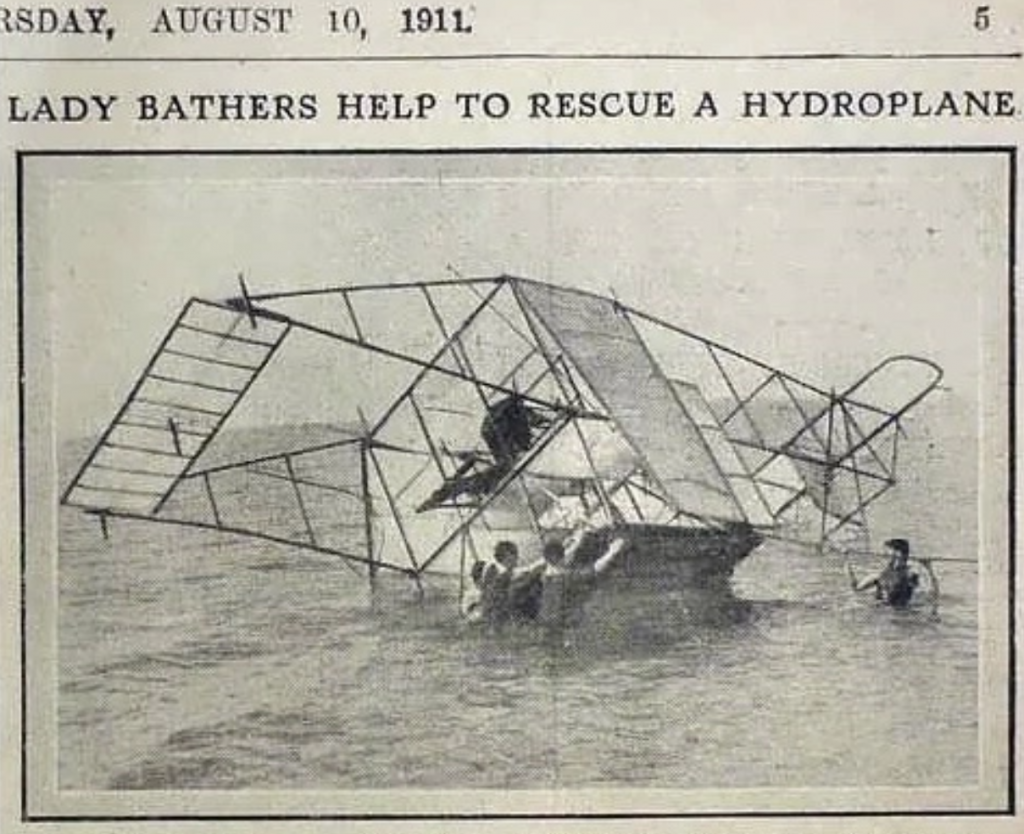

A month later, Flight magazine of 19th August 1911 writes:-

Mr Piffard’s Hydroplane Capsizes.

“After making one or two alterations to it, Mr Piffard had his hydroplane taken down to the sea at Shoreham on the 8th inst. Almost as soon as it was launched however, it capsized; but this was an emergency for which Mr Piffard and his assistants were well prepared, as they are all expert swimmers, and they soon had the machine ashore.“

Before Piff and his band of friends returned to carry on their hydroplane trials at Bungalow Town, on Shoreham beach, the nascent Shoreham Aerodrome had already become ever more popular with the British flying fraternity, with a number of aviators making it their base. 1911 was also turning out to be a ground breaking year for British aviation.

Earlier in 1911

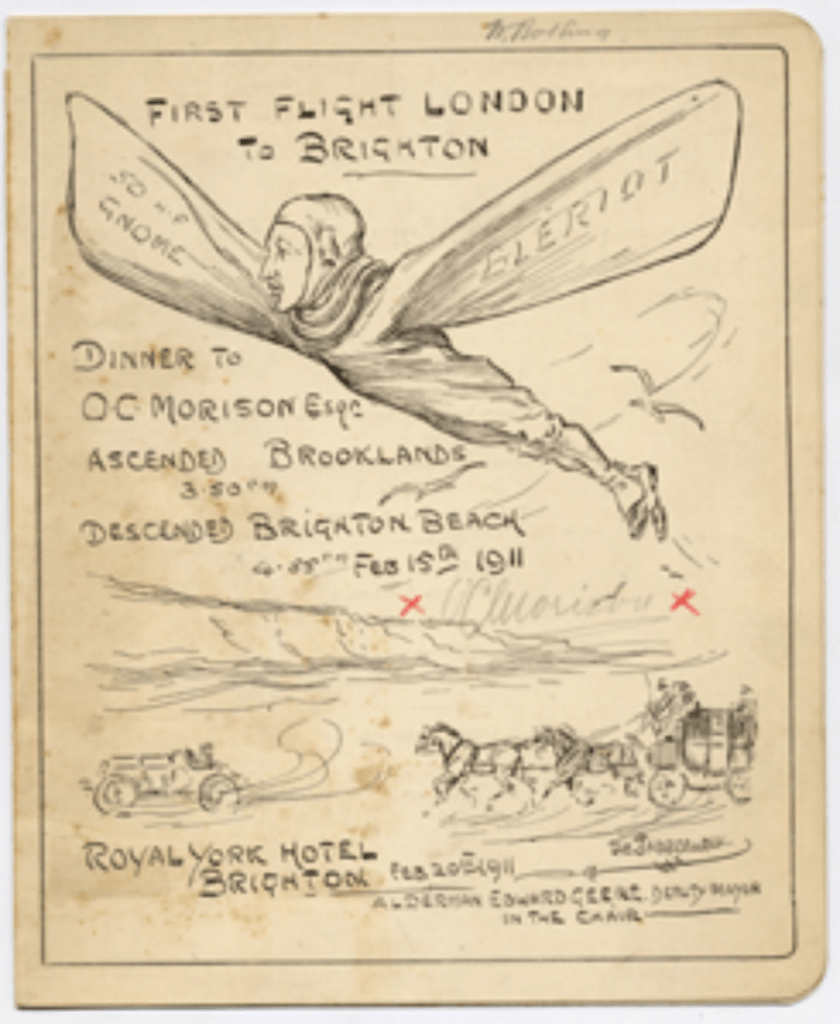

Brooklands to Brighton Flight, Harry Preston get a Memento, 14th Feb

The Northern Daily Mail reported on Thursday 15th Feb, 1911, that Oscar Colin Morison flew his Blériot monoplane from Brooklands to Brighton, a distance of 40 miles, in 65 minutes the day previously. The flight would have been quicker had Morison not gone via Worthing, although he insisted, “there was not a hitch throughout the journey”. He had only intended to fly to Cobham, but as the weather was so fine, on arrival he phoned up Harry Preston, (owner of the Royal York, and Royal Albion, hotels), to let him know he would be landing in front of the Royal Albion that afternoon. Descending on to the beach between the Palace, and West Piers, he mistook the pebbles for sand, and his plane crumpled under him on landing, damaging the undercarriage and prop. No injury was incurred, but Harry ended up with the broken propeller hung up in his hotel smoking room as a memento of the landmark occasion. A reporter on the spot informed Morison that, “you are the first aviator to drop down on Brighton beach”, to which he replied, “So I am told. I have no particular impressions about the flight except that it has been a jolly fine trip” .

In Harry Preston’s book, ‘Leaves From My Unwritten Diary’ 1936, page 79, he recalls:-

“In my smoking room I have many air mementoes, among them a broken propeller. Oscar Morison gave it to me- he smashed it on Brighton beach, on an historic day in February, a quarter of a century ago, when he flew from Brooklands to Brighton”

He continues:-

“The intrepid aviator told me at luncheon at the Royal York that followed, that he would have made better time, only he had got off his line of flight. He was circling to land, when he noticed that there was only one pier, and he knew Brighton had two. “Wrong town,” said he, and flew along the shore line until he sighted a town with two piers. It was Worthing he had mistaken for Brighton. Air navigation was not quite what it is now’

This lunch at the Royal York had been quickly arranged by Harry as a member of the Sussex Motor Yacht Club, in Morison’s honour. Afterwards they presented the aviator with a silver cigarette case in memory of his historic flight.

The Daily Graphic, Wednesday 1st March 1911, writes about Morison’s exploits, and his patronage of the new aerodrome at Shoreham:-

‘Brighton for the past week has been entertaining her first visitor to arrive by air, in the person of O.C. Morison, who safely landed upon the beach at Kemptown after a surprise flight from Brooklands. The aviator is now stormbound, and his 50 h.p Gnome Bleriot is causing great interest among the visitors and residents who have inspected it in its temporary home in a local garage. When the present gale has blown itself out- and to judge by the “glass”, this will not be for some days- the Bleriot will be wheeled along the front to Hove lawns, and from this spot Mr Morison intends to fly to Brighton and Hove’s new aviation ground, where during the coming summer the town hopes to have the pleasure of receiving all the air’s conquerors.’

After repairs had been carried out, Morison took his Bleriot to Shoreham, on 7th March 1911 becoming the first aviator to fly in to the Aerodrome, from there, flying above Bungalow Town, and over to Lancing College at the invite of the Headmaster, Reverend Henry Thomas Bowlby. He put down on the College cricket field but the bowling green surface meant the plane hurried on a tad more than he expected, running the Bleriot in to a grass bank, breaking the elevator and thus rendering the machine temporarily inoperable. Morison put this opportunity to good use, showing the captive audience of schoolboys over the aeroplane, and the explaining the purpose of the controls. Given their former pupil, Piffard’s, exploits the year previous, a foundation of lasting aviation interest had surely now been cemented.

Bungalow Town resident, and regular columnist for ‘The Daily News’, John Frederick Macdonald, of number 2, Coronation bungalow, Beach Road, described the scene of Morison’s arrival at Shoreham, giving a wonderful first hand account of not just how he saw it, but also a reporters eye view of how some of the other residents reacted to this novel event, for ‘The Daily News’, Tuesday 14th March 1911:-

‘At eleven o’clock this morning I behold Shoreham-on-Sea, a simple and picturesque little town of three thousand inhabitants, in a state of excitement and delight. Out on their doorsteps come the trades people of the inevitable High Street, and, shading their eyes with their hands, they look eagerly upwards. More ardent interest in the skies on the part of the weatherbeaten old boatmen; still more rapturous gazing at the heavens from the maidens of Shoreham- and all kinds of incoherent exclamations from a group of small boys. “What,” I ask timidly one of the Shoreham maidens, “what is the matter?”, “we’re waiting for Mr. Morison”, excitedly replies the maiden- most radiant of blondes. “He’s left Brighton. He may arrive at any moment. He-“ , “Who is Mr. Morison”, I ask ignorantly. Then as the blonde regards me blankly- “I’m awfully sorry I don’t know Mr. Morison. In fact, it’s disgraceful of me. But I’m a stranger to these parts, and I’ve come here to lead the simple life, and-“

“That’s ‘im- no it’s not”, cries a boatman. “’Ere ‘e comes- no ‘e don’t”, shouts a small boy.

“You don’t know Mr. Morison?” exclaims the radiant blonde, with indignation. “Why we’ve been expecting him for five days. And I tell you he’s left Brighton at last. And I—“

“Here he is, here he is”, cries another maiden. “Coming along like mad”, declares a boatman. “Ooray”, yells a small boy. A whirring noise in the heavens. All eyes strained upwards. The whirring becoming stronger, almost thunderous. And over the narrow High Street of Shoreham, at a height of six or seven hundred feet, an aeroplane flies by. “That’s Mr. Morison”, gasps the blonde. And she and the other charming maidens, and a few of the tradepeople and a number of battered boatmen and, of course, all the small boys, run off down the High Street, and over the Norfolk Bridge, and along the high road that leads to the field in which Mr. Morison, the flying man and the idol of the South Coast, has descended.

“IT”

It was an admirable flight. I am informed that Mr. Morison (who has travelled successfully from Brooklands to Brighton in his Bleriot machine) came over to Shoreham from the”Queen of the Watering Places”, a distance of six miles, at a speed of a mile a minute. Admirable, too, are the flights he made twenty four hours later—over Lancing College and over Bungalow Town, that colony of villas, chalets, and other strange miniature habitations formed out of abandoned old railway carriages, which has sprung up, quaintly, amazingly, to the number of three hundred on Shoreham Beach. So is Mr. Morison, most justifiably, Shoreham’s hero. So does Shoreham flock to the field and surround the shed, in which the aeroplane is housed. So does Shoreham proudly refer to the field as “OUR Aviation Ground”. So does Shoreham triumphantly allude to Mr. Morison as “OUR Flying Man”. And so—since Mr. Morison is stated to have declared himself satisfied with the field—so does Shoreham confidently announce that its fortune as a popular seaside resort is made.

“That’s what we wanted—a flying man, and I’m sure we’re most grateful to Mr. Morison for taking a fancy to our town”, a tradesman informs me. “With an aviation ground, and a flying man, there’s no reason Shoreham shouldn’t become a fashionable place. Flying, there’s nothing like it. Flying is what you London folk call the limit. Why, I can see Shoreham swelling and swelling in size, until Brighton and Worthing get green and yellow with envy and jealousy. To borrow another word from the Londoners, Shoreham is going to be IT”

In “The Brass Bell”

I cannot exactly imagine the “face” of Worthing and Brighton discoloured with jealousy; but I do know that I myself am envious of Mr. Morison’s popularity. A week ago I made quite a little sensation by appearing in High-street. I was a newcomer—and the old boatmen saluted me, and the small boys stared and gaped at me, and the blondes and brunettes gazed–O exquisite moment—curiously at me as I passed by. Gone, those attentions. Now I am a nobody; only Mr. Morison counts—and so how I wish I were Mr. Morison the idol of Shoreham! The fact is, one ought nowadays to be a flying man. Once it was splendid to be a Caruso, or George Alexander, or Wilkie Bard, or Sandow, or Prime Minister, or King; but the hero-worship of the hour is reserved for the gentlemen who fly—a throne up in the air excites infinitely more respect and enthusiasm than a throne in a palace. Is not simple Shoreham, since Mr. Morison’s coming, a new town? The whirring of the Bleriot has shaken it out of its slumber, frantically modernised it—rendered it ambitious, feverish, hectic, delirious. The very children now babble of aeroplanes. Old Joe the grocer, aged seventy, mumbles about aeronautics, as he searches for tins of sardines and packets of tea behind the counter. At the bakers, the “Standard” bread gossip has given way to aviation gossip. And one talks and talks of nothing but flying at the chemists, at the tobacconist’s, at the bootmaker’s, at–.

“Two Bass—one dry ginger—yes, now that flying ‘as come to Shoreham it’s going to make a powerful bit of difference”, states the landlord of “The Brass Bell”. “There was at least forty motors come over from Brighton today”, says a customer. “As many more from Worthing”, states another. “People will be coming from everywhere—just get flying and you get the money”, declares a third. But the landlord of the “Brass Bell” goes even further. He vows that simple Shoreham must be advertised—“you know, great big posters in the railway stations, on the ‘oardings, in the papers; pictures of a bloke flying, with the sky painted all blue, and words written underneath it like this—‘Shoreham for Flying. Shoreham and Air. Shoreham the ‘ome of Aviation and the Centre of ‘appiness and ‘ealth. Shoreham for the English’ “.

“What a time it will be!” exclaims a customer. “We shall have to have a theatre and a music hall, two shows a night”, says another. “You’ll have to enlarge your hotel. You know, a winter garden, and a band, and a garage, and an American bar—cocktails; and coffee beans placed handy on the counter for nothing”, advises a third. “Trust me”, replies the landlord. “Now that flying ‘as come to Shoreham, well, old Shoreham’s going to sit up”.’

James Valentine sets up at Shoreham

With a new railway station having been built at Shoreham airport, called the ‘Bungalow Town Halt’, the previous October, Shoreham Aerodrome was now attracting aviators of distinction, among them, James Valentine, who, as the Daily Graphic, Weds 1st March, 1911, reports further on from the previous article:-

‘Mr Valentine, who flies a passenger carrying machine of his own design, has decided to make the new ground his headquarters, and during the summer will conduct a series of week-end trips between Brooklands and Brighton, a distance of 34 miles, via Leatherhead, Dorking, and Horsham. The railway line will make a splendid guide, and prevent any chance of the machine and its occupants arriving at some rival seaside resort by mistake. Mr Valentine’s spare time is to be given to perfecting a machine of English make which will land and rise from the sea, so that he could not have chosen a better ground for his work.’

The Brooklands to Brighton Race, 6th May

The Brighton beach landing had inspired Harry and his brother, Dick, (Hugh Richard Preston, who helped run the two hotels with Harry, the Royal York, and Royal Albion), to put up a prize for a race from Brooklands to Brighton via Shoreham as the turning point, on the 6th May 1911, a large balloon was attached to the Palace Pier acting as the finishing marker for the competing aviators. The proprietor of the Palace Pier, Mr Rosenthal, put up £80 for first prize, while Harry Preston put up £30 for second place. There was also a third prize of £20.

There were 8 entries for the race, but for various reasons only four aviators started, Graham Gilmour on a Bristol biplane with Gnome engine, Lieutenant Snowden-Smith on a Farman biplane with Gnome, Howard Pixton on an Avro D type biplane with a Green engine, and lastly, Gustav Hamel on a Bleriot monoplane with Gnome. It was a handicap race, with Gilmour starting first, followed by Snowden-Smith 4 minutes later, Pixton ought to have been next, but was at the time trying to win another prize, while Hamel took off 12 minutes after Gilmour, who was already out of sight, and Snowden-Smith was disappearing in to the haze ahead. Pixton got going 8 minutes later, having completed his flight with passenger, competing for the Manville Prize.

The four aviators missing from the starting line up were:-

J Ballantyne (Farman biplane)

Mr Gordon England (Bristol biplane)

Mr C.H.Cresswell (Bleriot monoplane) Got lost in fog flying from Hendon to Brooklands.

Mr Hubert (Farman biplane) Also lost in fog flying to Brooklands.

Interest in the race had drawn crowds along the route, The Globe, 6th May, 1911, reported:-

“All the competitors made two circuits of the course before heading for Brighton. There was great enthusiasm among the spectators, and there were high hopes that a fine race would ensue. – Along the route- Holmwood (three miles from Dorking)- Four aeroplanes passed here at 3.40. Large crowds had assembled in the town, and loudly cheered as the machines passed. Lancing.- Three aeroplanes have passed here heading for Shoreham. Shoreham.- Mr Hamel passed here at 3.50. Another machine, a biplane at 4.7.”

The ’machine’ at 4.7 would have been Lieut. Snowden-Smith.

The Lichfield Mercury, Friday 12th May 1911, reporting a week later of the finish line at Brighton, stated:-

“Quite early in the afternoon an immense crowd gathered at Brighton, filling the front from pier to pier and even beyond. Just after four o’clock the first aeroplane hove in sight in blaze of the sun. It was flying high and dipping a little in the wind, which was evidently stronger at that height than on the ground, where the flags scarcely fluttered. Slowly as it seemed, but surely, and heralded by a burst of cheers that rippled along the front, it gradually dropped and crossed the pier accurately in the middle. One saw the number clearly, though it was scarcely necessary for identification, because it was known Mr Hamel was flying the only monoplane in the race.”

It continues:-

“From the terrace of the Royal Albion Hotel, Mr Hamel’s father “snapped” his son with a hand camera as he came sailing triumphantly past, and turned to congratulate his wife on the success of the young aviator. After circling twice round the pier head, Mr Hamel flew back to the Shoreham Aerodrome, and afterwards departed for Brooklands.”

The ‘Sussex Express, Surrey Standard and Kent Mail’, picks up the story:-

“The first sight of an aeroplane renders one speechless for a time, but as Mr Hamel on his Bleriot monoplane gets nearer to the great mass of people the volume of cheers gets louder and louder. He is scarcely out of sight when Lieut. Snowden Smith, on his Farman biplane, arrives, and Mr Gilmour, on a Bristol biplane, comes next. The ease and grace which characterised the flying won great admiration. The times taken by these three competitors were:- Mr Hamel, 57 mins, 10 secs.; Lieut. Snowden Smith, 1hr. 21 mins. 6secs.; Mr Gilmour, 1hr. 37mins. 0secs.”

Explaining Pixton’s absence, it reports:-

“Mr Pixton, who descended on his all British Roe biplane on Plumpton Racecourse, received a warm welcome there. The people decorated his machine with primroses, and hundreds of names were written on it. He made the journey to Brighton after tea.”

Lieut. Snowden-Smith, who had finished second, it was pointed out, had missed the Shoreham turn, the competitors were supposed to keep west of the Adur Railway bridge before turning for Brighton, the Lieutenant had gone inside, to the east, so was disqualified, leaving Gilmour, who had finished in 1 hour, 37 minutes, promoted to 2nd place. From Shoreham later, Hamel flew back to Brooklands in just 34 minutes, suggesting a strong headwind may have held them up during the race. Gilmour stayed the weekend at Shoreham, possibly taking advantage of the entertainments along at Bungalow Town, when he left, he flew to Portsmouth, according to a report in the Jarrow Express, Friday 12th May 1911:-

“The first aeroplane to pass over Portsmouth made its flight on Tuesday from Brighton (Shoreham aerodrome actually) to Gosport, as a sequel to last Saturday’s aerial race from Brooklands to Brighton. The aviator was Graham Gilmour, who paid a visit by air to his brother in-law, Fleet Surgeon Capps, one of the staff of Haslar Naval Hospital. Without alighting at Portsmouth, the aviator flew across the harbour to the hospital, and landed safely in the grounds, where it was reported that he had “shelled” a fort blockhouse at the entrance to Portsmouth Harbour with oranges”

Stuck in a Tree at Haywards Heath

Oscar Morison decided to fly to Haywards Heath on Tuesday 9th May, taking Eric Cecil Gordon England with him as passenger. It was an incredibly costly business maintaining their machines, especially when they crashed, so occasionally, when they turned up at a town or village, where crowds would very soon gather, they could charge between a pound and a fiver a time for a quick flight, which was not unknown among the aviators of the time. Reported in the London Daily News, 10th May 1911, it states:-

‘Mr Morison, the well known aviator, had a narrow escape from a serious accident tonight. Mr Morison arrived here from Shoreham yesterday on his biplane, and arranged to return tonight. A start was made about half past seven, Mr Gordon travelling in the machine as passenger. The aeroplane had only just started its flight however, when the engine suddenly stopped, and the biplane came down rapidly at the edge of a wood near a railway line. The crowd who had watched the ascent ran to the spot expecting to find the aviators seriously injured. On their arrival however, they found that the aeroplane had not reached the ground, the wings having been caught in the branches of an oak. The aviators, who were uninjured, were rescued by means of ladders. The biplane was considerably damaged.’

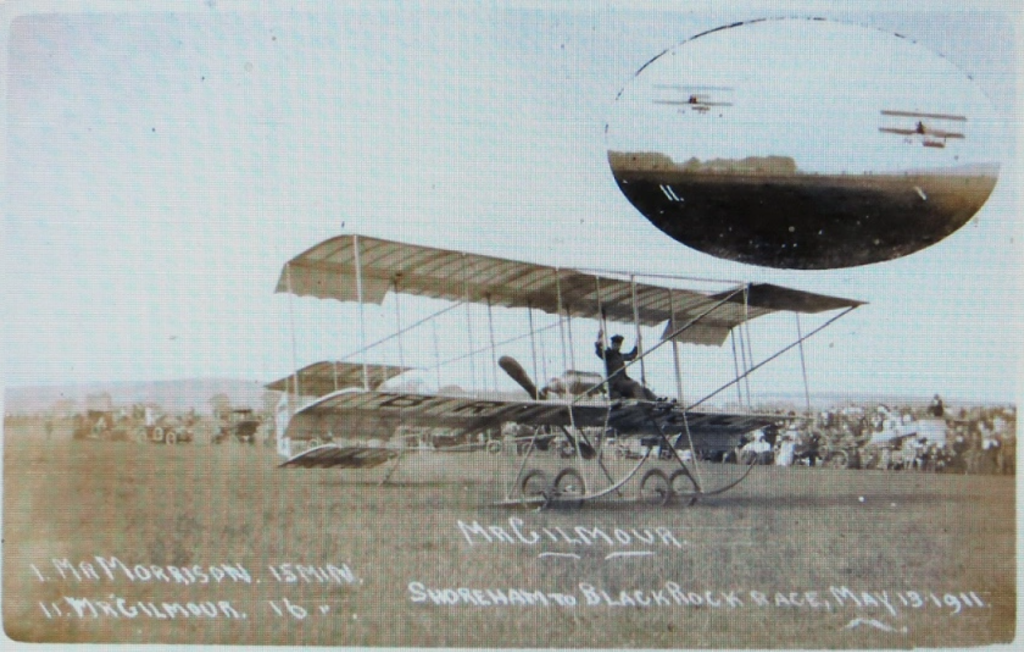

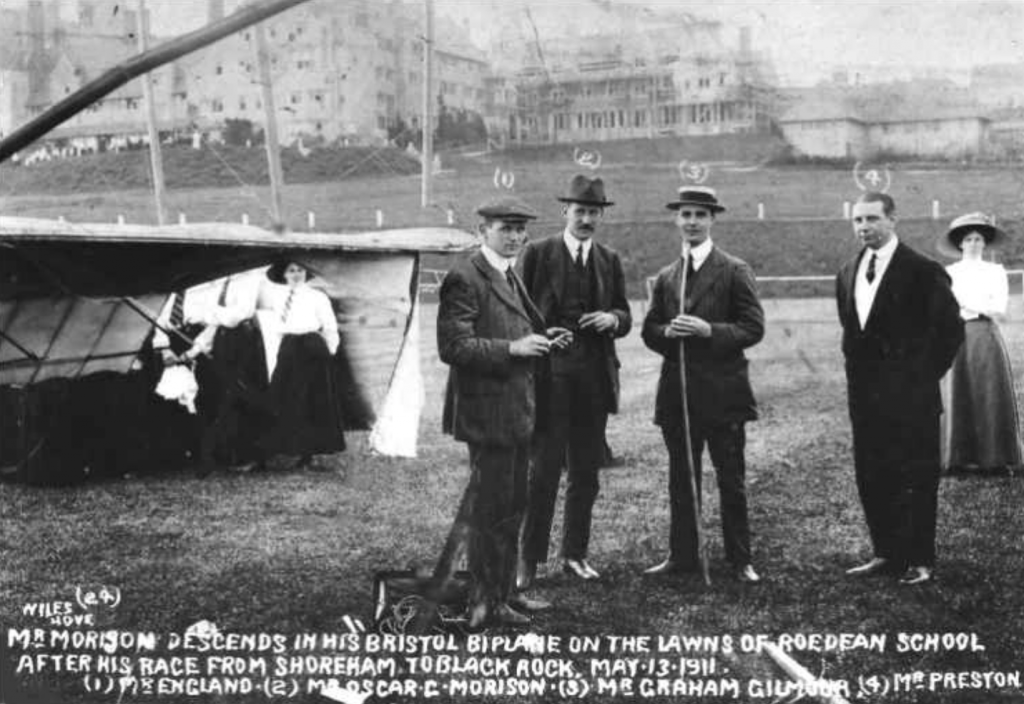

The Shoreham to Black Rock Race

On 13th May 1911 Morison was in a well-publicized air-race with Graham Gilmour from Shoreham Aerodrome to the eastern boundary of Brighton at Blackrock, Morison taking the straight course passed the winning post one minute before Gilmour. Reported in the Belfast News-Letter of May 15th 1911, it states:-

“The contestants used Bristol biplanes of equal power, but whereas Morison went straight for the winning post at a height of 800 feet, Gilmour flew farther out to sea and rose to 1100 feet. What might have been a neck and neck race consequently ended in Morison’s favour by about a hundred and fifty yards. The winner crossed the line just after five o’clock, having covered the course in a quarter of an hour. He, however, made a bad landing in the grounds of Roedean College, breaking his skids and damaging the elevator. Gilmour, who descended there, alighted perfectly, and afterwards flew back to Shoreham.”

Shoreham Aerodrome inauguration. 20th June 1911

Reported in the ‘Flight’ magazine of 1st July 1911, the Mayors of Brighton, Hove, and Worthing officially opened the ‘Brighton and Shoreham Aerodrome’. It writes:-

“The ceremony was preceded by a luncheon, at which the aims of the promoters were explained, and it was stated that the proposals included a clubhouse on the ground. The ground is about a quarter of a mile square, but surrounding it is a flat stretch of country about a thousand acres in extent, free from trees, and eminently suitable for flying purposes. Already a large number of hangars have been erected, and the arrival of the competitors in the European Circuit race on the grounds this week, from which point they “take off” for Hendon, should give the fine aerodrome a splendid send off. Brighton should be under a great obligation to the enterprising men who have thus given it, at this early stage, so important a chance in alluring aviators to the district”

The Mayors of Brighton, Hove, and Worthing, at the occasion of the inauguration of ‘Brighton and Shoreham Aerodrome’ 20th June 1911

Written by Andy Ramus 2021

For the additional article chapters follow the links: