Article written by Ken Wilcox

Introduction

By the latter half of the 19th century the continuing industrial revolution in iron and steam shipbuilding had resulted in the decline of large wooden commercial ship construction. However from 1880 to 1890 the British and Commonwealth Merchant fleet still made up 50% of the world`s sailing ship tonnage and when steam ships were also considered then the combined fleet constituted some 60% of the world`s registered tonnage. Britain would remain the world’s principal maritime nation until the end of World War II. It is into this climate of maritime dominance the Osman Pacha was launched on a spring tide in February 1878. The launch marked a watershed in Shoreham`s long commercial and naval ship building history which had been one of the most important economic elements of the port’s activity since the mediaeval period. As the new century dawned the artisan`s skills turned to smaller recreational yacht building and the memories of Osman Pacha ebbed away……

What was her story ?…

`The Old` Shipyard

Shoreham was no exception to this revolution and by 1880 the three principal 19th century commercial shipyards had ceased production. Iron sailing and steam ship construction moved to centres, mainly in the North and Scotland, where the raw materials were available. The `Old Yard` situated on the north shore of the river east of the Norfolk bridge had, as the name suggests, a long and distinguished history in both Naval and mercantile construction dating back at least to the 17th century and was the final yard to close. It had been the most prolific of the Shoreham yards and had an enviable reputation for producing vessels of excellent quality. Many of the shipwrights, sail and ropemakers, lived close by in West Street, where a sail loft and ropewalk are still in evidence. The yard was owned by John Edwardes in 1800 who then took into partnership James Britton Balley, a Littlehampton and Dartford trained shipbuilder. Balley married John Edwardes’ daughter and developed the yard, becomimg one of the town’s most successful businessmen.

Balley died in 1863 and the business was taken over by W. May, probably a relative of J. May who together with Mr Thwaite had built ships at Kingston, a mile to the East of the Old Yard, from 1838 to the 1860`s. W. May continued the yard`s fine tradition until 1875 when A. Dyer & Sons took over and built a succession of four large sailing ships, the Osman Pacha being the fourth. No doubt she was named after the Ottoman Field Marshal who gained fame and British sympathy during the Ottoman-Russian war of 1877.

Mr. Balley had also owned the Swiss Gardens which were purchased by Edward Goodchild. A publican he had been landlord of the Buckingham Arms and had shares in several ships and property interests. Whether the Osman Pacha was built as a speculative venture by Mr. Dyer and then purchased by Mr. Goodchild or whether she was ordered by him is not known. Unfortunately, Mr. Goodchild died age 63 on 14th January 1878 shortly before the launch of the ship in February 1878 and the vessel formed part of his estate.

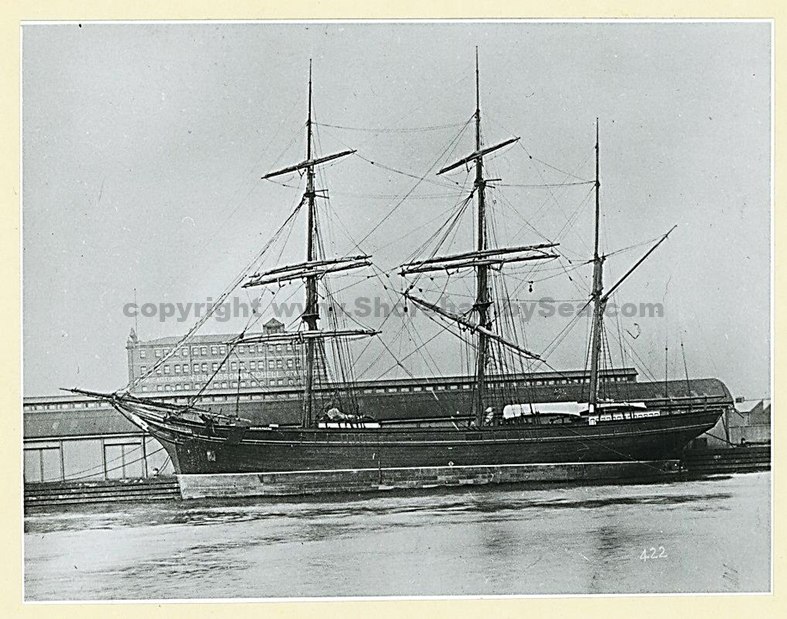

1877. The barque Britannia ready for launching at the Old Shipyard. The image Illustrates the appearance of the very similar Osman Pacha prior to her launch one year later. (Courtesy of the Marlipins Museum.)

1877. The barque Britannia ready for launching at the Old Shipyard. The image Illustrates the appearance of the very similar Osman Pacha prior to her launch one year later. (Courtesy of the Marlipins Museum.)

The Build

Built originally for the West Indian trade and constructed of oak she was a three masted barque (Square rigged on the fore and main masts with fore and aft sails on the mizzen mast).

Length 142.5 ft. Breadth 29.8 ft. and Depth 17.8ft. Official No. 77078.

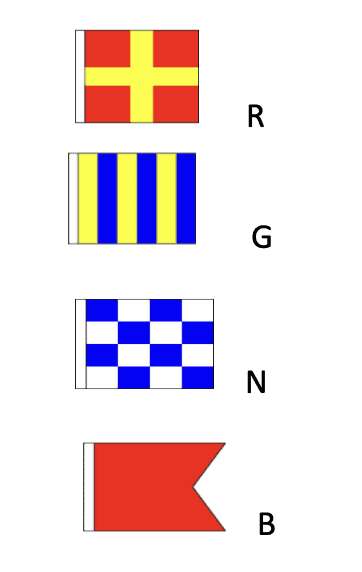

Signal letters

Hoisted vertically at the mast head they were the unique identification code a ship was issued with on being registered under the British flag. Together with the Official Number they continued as long as the vessel remained on the British register

Her Gross tonnage was 509, Register tonnage 497, and she could carry about 800 tons of cargo. (Gross registered tonnage was a measure of total enclosed volume whilst Nett registered tonnage was the Gross tonnage minus the volume of spaces where cargo could not be carried.)Thus Nett tonnage represented the cargo carrying volume, not the weight.

She was built under Lloyds Special Survey and Classed A. for 13 years. (Class was used by insurers for risk assessment. Ships were built to certain standards and when overseen by a Lloyd`s surveyor they attained the highest class). The vessel was salted which entailed filling all open spaces between frame timbers with rock salt, an excellent wood preservative which resisted decay. The classification society, in this case Lloyds, would thus grant an extra one or two years before the next classification survey was due.The hull of the vessel was copper fastened, and the submerged section sheathed in felt overlaid with yellow metal which had been developed by G.F.Muntz in 1832. This was a copper/zinc alloy which was as efficient as copper but somewhat cheaper and protected the hull from marine boring worms as well as keeping marine growth to a minimum. Thus the need for dry docking was reduced and with a cleaner hull speed was better maintained.

Two deck houses were situated on the upper deck, the after one generously fitted out in mahogany and pitch pine. Osman Pacha was a fine vessel built to the superior standards of timber ship construction and was launched on the highest spring tide in February 1878.

The ship was put up for auction on the instructions of Mr. Goodchilds’ executors on 6th June 1878 at the Royal Exchange, London. Noted in Lloyds register of 1878 the new owners were A. Dyer ( builder) and E.P. Bates a Liverpool owner of some notoriety known as `Bully Bates`. However the ship inexplicably remained laid up in Shoreham for some two years.

British wooden barque Delta similar to the Osman Pacha off Swansea flying her signal letters, ensign, house (owners) flag and on the foremast the pilot jack requesting a pilot. c. 1880. Painter unknown (Courtesy of wales online.co.uk) The pennant below the ensign signifies all flags visible are to convey their International code meaning. Taken to London, probably towed, in the summer of 1880, she was dry-docked at Cubitt Town on the east side of the Isle of Dogs in September 1880. After renewing the sheathing and minor repairs Mr C. Davey, Lloyds surveyor noted:

“The vessel now in good condition and eligible to continue as classed”.

The owner was noted as E.P.Bates & Sons. Mr Dyer appearing to have sold his interest. In 1881 after dry docking a new owner is listed on Lloyds Register: Mr R. Berridge of Carlton House, The Cedars, Putney. However the vessel is still not put to trade but again inexplicably shifts to lay up, this time on buoys in the Import basin of the nearby West India Dock with a Captain Christensen appointed. She remained tied up to the buoys in the West India Dock with no Master noted throughout 1882 and in 1883 was put up for sale. 1884 saw the vessel still for sale and with no buyer she remained in lay up until December 1888 when she was moved to the Ratcliff dry dock in the London Docks.

This proved to be the end of a very unusual long lay up of nearly 11 years. In an interview with an Australian news reporter in 1890 the captain mentioned a dispute among the original owners. Any litigation must have been long and complex given the time the vessel was inactive, however to date no details have been discovered. In simple terms British shipping was on the crest of a wave in the period under consideration and there was still profit to be made in sail. Many steam ships were still inefficient and despite the gains made in steam technology there were profits in sail. It is therefore unlikely that the economic climate was a reason for the vessels` long inactivity.

Trading 1889.

After finishing repairs and a successful survey in 1889 new owners were noted as Macbeth and Grey of 20, Clyde Place, Glasgow, who were well known shipowners and would finally put cargo in the vessel. A Master, Captain Thomas Mellis of Kieth, was appointed in January and the vessel shifted to the nearby St. Katherine’s Dock, below and close to Tower Bridge. All her moves in London would have been accomplished by employing temporary crews and using licenced watermen to conduct the short river and dock shifts, utilising tugs when needed.

The Crew

Commencing to load her first cargo for South Africa the master would `sign on` a permanent crew.

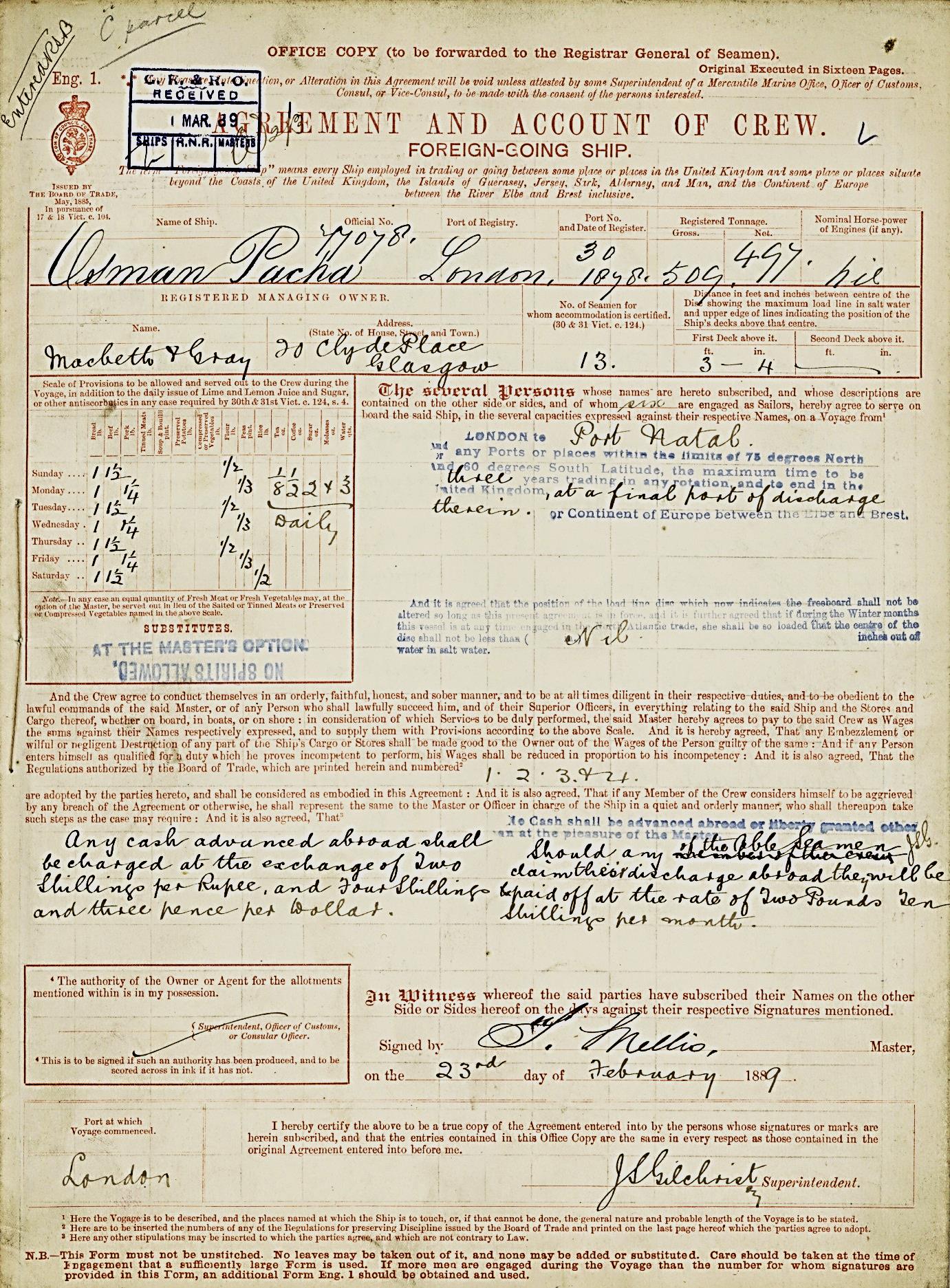

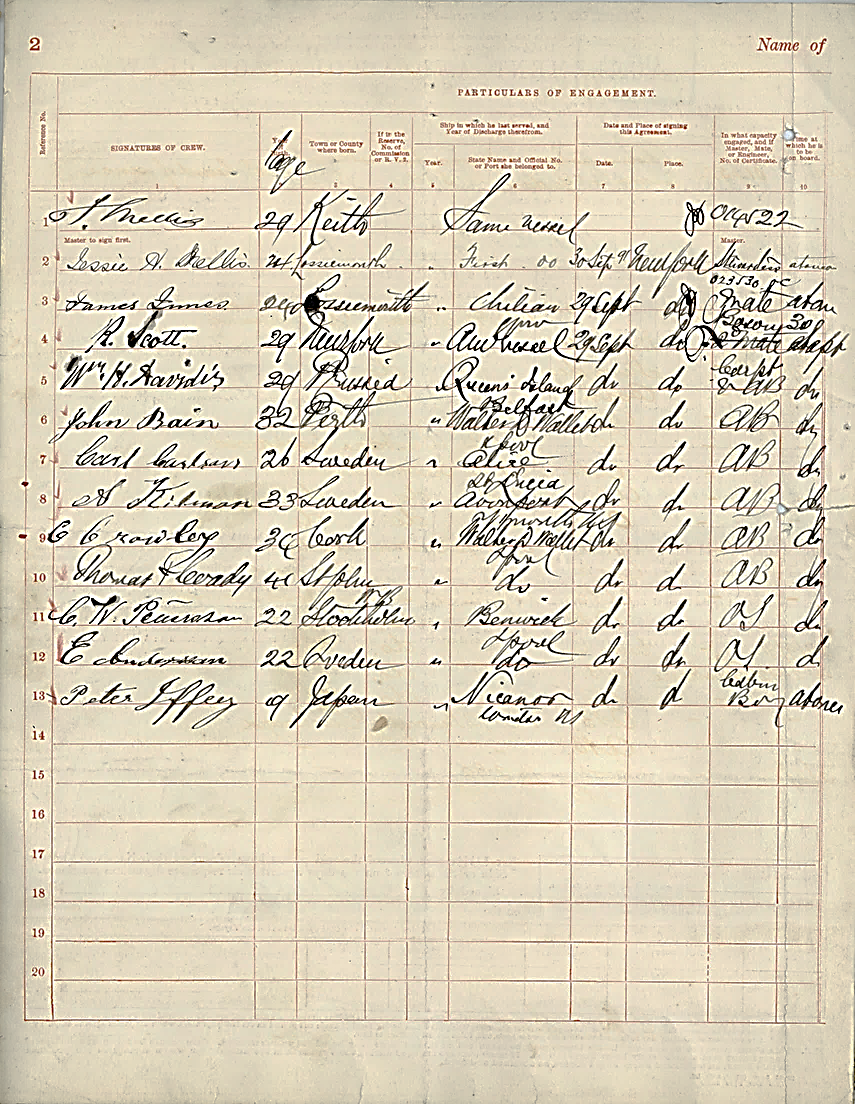

THE AGREEMENT AND ACCOUNT OF CREW. Eng.1.

Foreign-Going Ship.

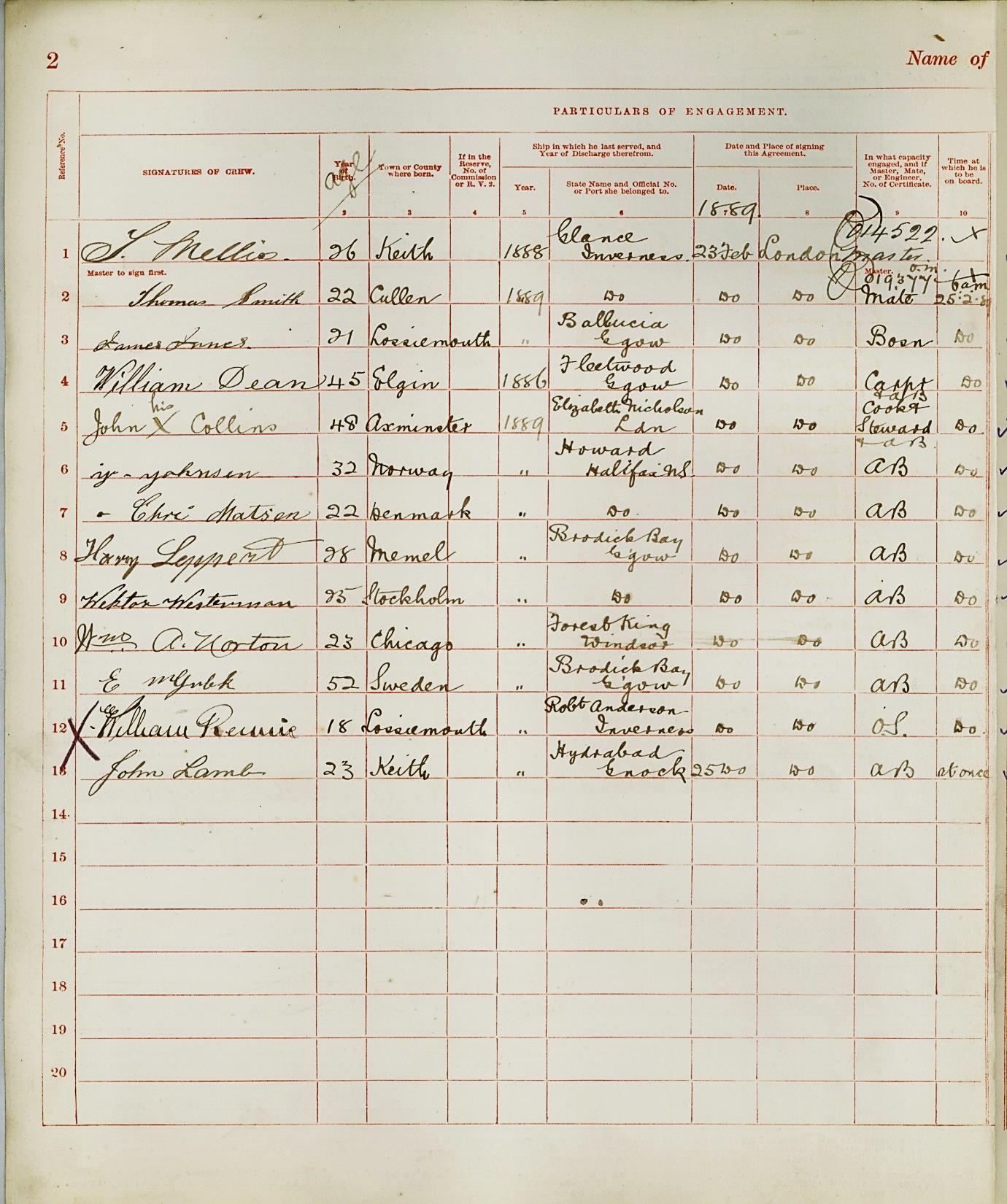

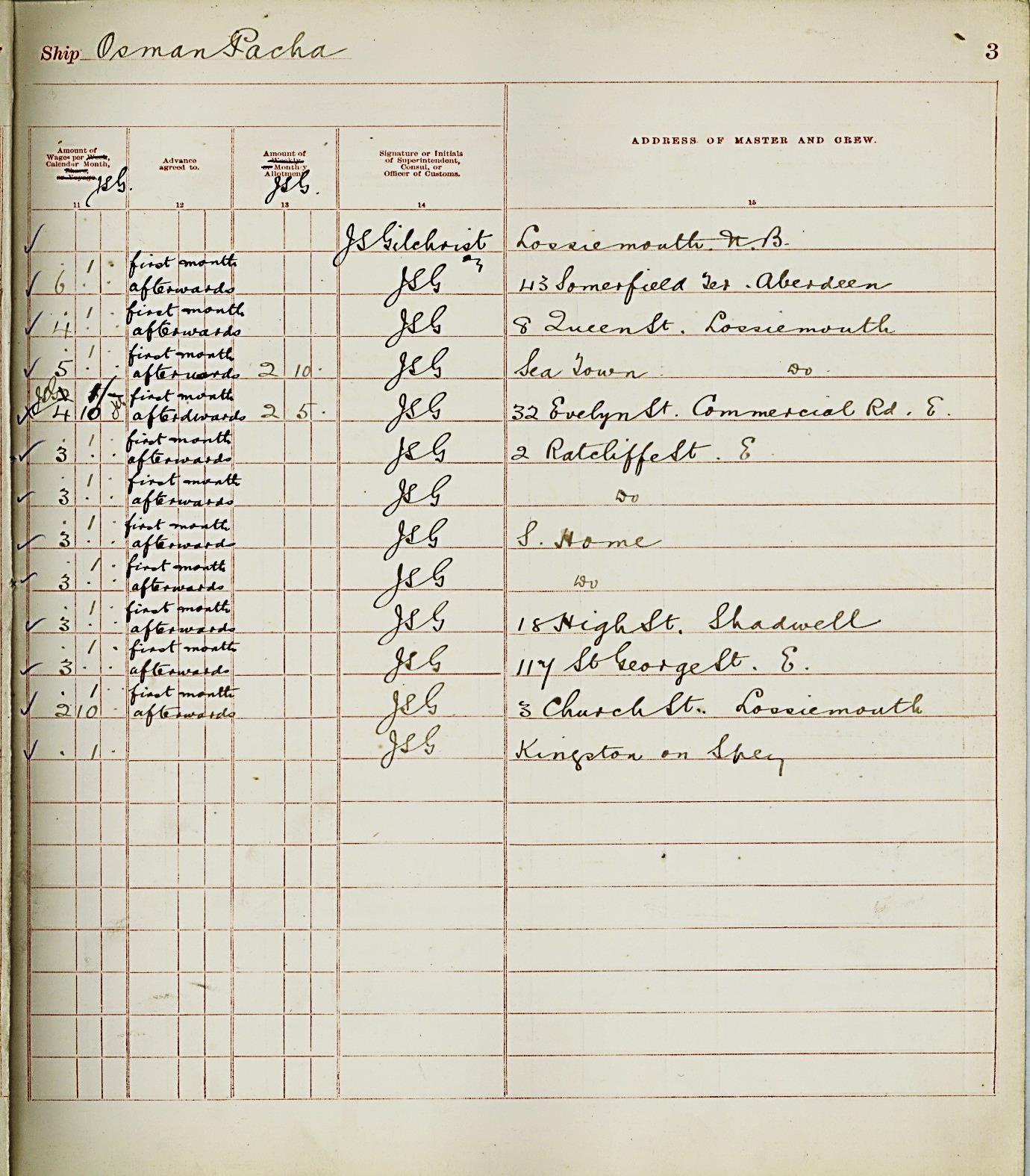

This was the official document the Master and crew would sign as required by The Merchant Shipping Act of 1885. It was essentially a three- year contract between the crew, Master and shipowner which was signed and witnessed in the presence of a Board of Trade Superintendent at the local shipping office. A date for reporting on board was laid down as were victualling and fresh water allowances together wit clauses on behaviour and discipline. Levels of pay were agreed as were conditions for cash advances and the means to send monies to dependents via the shipowner or his agents, known as allotments. The crew consisted of the Master; Mate; Bosun; Carpenter/A.B. Cook/steward A.B. and 7 Able plus 1 Ordinary seamen. The Master and Mate were 26 and 22 years old, and they had sailed together on a previous ship and would have had a close working relationship. It is also probable that the Bosun would act as 2nd Mate and keep a watch at the tender age of 21. The responsibility of command, or that of assuming responsibility for a watch at such a young age was not unusual. Experience and sea time were quickly acquired during the long voyages under sail. The crew were divided into two watches working four hours on and four off with each watch in the charge of a Mate. When weather and circumstances required it would be “all hands- on deck” turning out the watch below together with the cook and bosun. (see appendix 1 and 2 for details on conditions and crew).

General cargo work at St. Katherine’s Dock 1899. `London Docks` by John Pudney

General cargo work at St. Katherine’s Dock 1899. `London Docks` by John Pudney

Having loaded general cargo the vessel anchored at Gravesend on 27th February for final clearances and departed for Port Natal, South Africa where she arrived on the 24th June having sailed some 6,000 + nautical miles. After discharge she proceeded on the 1,500 mile voyage to Port Louis, Mauritius to load sugar for New York. This would have been loaded in bags from barges whilst the vessel was at anchor.

Port Louis 1899 viewed from Signal Hill. Vessels awaiting loading. (Courtesy of the Museum of Mauritius).

Port Louis 1899 viewed from Signal Hill. Vessels awaiting loading. (Courtesy of the Museum of Mauritius).

Arriving in New York on 21st October after a voyage of some 9,000 miles Captain Mellis reported damage after experiencing a hurricane on 14th October in the North Atlantic. The wind was from the north west shifting to the north east and lasted for three days. The storm “carried away the foretopmast tresstrees,( a timber reinforcement a to strengthen the topmast and main mast connection) broke the main rail, ( main bulwark around the weather deck) and stove in a boat.”

On the 13th November she began the 7,000 + miles voyage from New York to Cape Town with a general cargo at a freight rate of £2 / ton.

1890

After discharging in South Africa she proceeded to Mauritius, once again to load sugar, this time for Melbourne Australia.

Sailing from Port Louis on 29th April she completed the 5,000 + mile voyage to Melbourne on 3rd June, some 33 days out of Mauritius. Two passengers, Mr and Mrs W. Stanley, had taken passage from Port Louis and were landed safely.

Mr. A. M. Campbell, a newspaper reporter for the Melbourne Argus, boarded the vessel and interviewed Captain Mellis. I have quoted his article extensively.

“The Osman Pacha has arrived in port from Mauritius laden with sugar. She is a barque rigged vessel of pleasing appearance, and is one of those smart clippers of Shoreham build of which there were several representatives sailing in and out of this port a few years ago. Although launched in early 1878 she saw no active service till 18 months ago. This curious and somewhat uncommon incident in a vessel’s career was due to a dispute among the original owners and the barque during the years that elapsed ere the difference was adjusted was laid up in the West India Dock. To all intents and purposes she is a new vessel. At sea the behaviour of the vessel is all that could be desired. The Captain reports that on sailing from Port Louis she carried strong North Easterly trade winds to Latitude 35 deg. S and 55 deg. E. Strong westerly gales then set in with the wind ranging from N.W to S.W. accompanied by high seas. During the worst of the weather the barque ran dead before everything ( wind directly astern) to a position 118 deg E. and 41 deg S. when westerly light airs were experienced until making Cape Otway. Calms and light airs were then experienced until arrival at the Heads on the 2nd June inst. after an excellent passage of 33 days. She will discharge cargo up the river”.

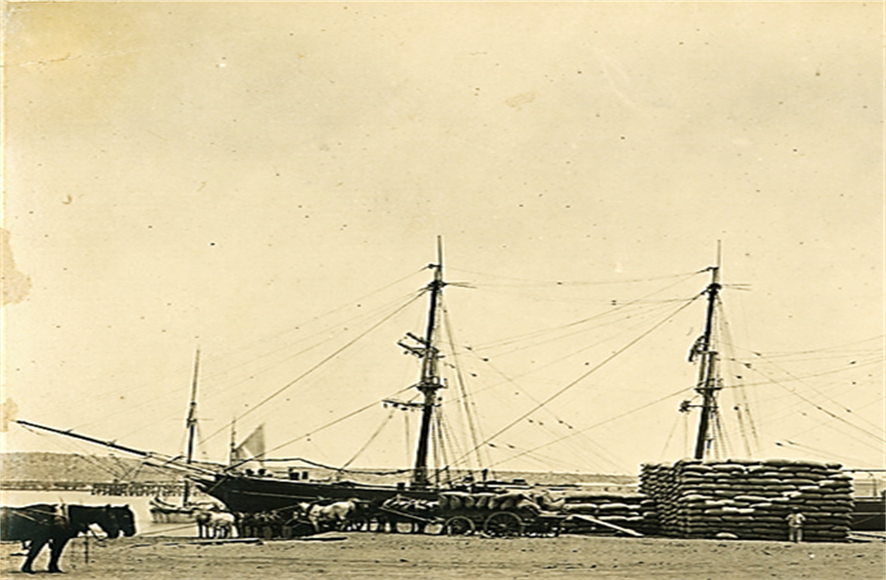

The only discovered image of the Osman Pacha. In ballast waiting to load coal for Port Augusta, Melbourne, June 1890. (Courtesy of the Library of South Australia.)

The only discovered image of the Osman Pacha. In ballast waiting to load coal for Port Augusta, Melbourne, June 1890. (Courtesy of the Library of South Australia.)

After discharge the vessel was fixed to load a cargo of coal on 29th June probably by the agents Charles Jacobs & Son at a freight rate of 22s. 2d per ton. Masters were becoming less involved in ships`s business as telegraphic communication extended around the globe and owners were more easily consulted. She sailed for Port Augusta in the Spencer Gulf a voyage of some 700 miles along the South Australian coast. Entering the southern entrance to the gulf she was unable to obtain the services of a pilot. Captain Mellis decided to sail on independently and, due to an incorrect chart, the vessel grounded on the 8th July. The ship was not in any immediate danger and the master sailed up to Port Augusta in an open boat and returned with a pilot. The ship was re-floated with no apparent damage on the 14th July and berthed that day.

After discharging coal the vessel loaded 6,400 bags of wheat valued at £46,000 and 17 stud sheep valued at £1,500 bound for South Africa. She set sail for Port Elizabeth on 5th August and arrived in Algoa Bay on the 30th September having undergone what must have been a difficult passage of 6,000 miles against the prevailing westerly wind and easterly current.

A barque loading bagged wheat in Port Augusta c. 1890 (Courtesy Library of South Australia)

A barque loading bagged wheat in Port Augusta c. 1890 (Courtesy Library of South Australia)

After discharge in South Africa she proceeded on the 1,500 miles voyage to Mauritius on 3rd November to load sugar for Kurrachee. (old spelling of Karachi then part of British India, now Pakistan). Arriving in Port Louis on the 13th November she left for Karachi on 6th December.

Trading 1891

Crossing the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea she arrived in Karachi on the 16th January to discharge the sugar.

Kurrachee (Karachi) Harbour c. 1890. (Source unknown)

On the 27th January she left Karachi for Chittagong, situated on the eastern side of the Ganges Delta, a voyage of some 3,000 nautical miles passing around the entire Indian coast.

Whether the ship was loaded or in ballast is not known, however it would be extremely unusual to undertake such a long voyage in ballast and we can only speculate on the type of cargo. Sailing ships had to load some form of solid ballast when empty for reasons of stability, in this case some 200-250 tons, about 1/3 of cargo capacity would be needed. Doing so increased costs and time and was avoided wherever possible. Osman Pacha arrived Chittagong on the 13th March after 41 days and departed for Mauritius, probably loaded, after a stay of 13 days on the 26th March voyaging some 4,100 nautical miles to load sugar again. Spending 14 days in Mauritius she left for New York on 14th June. More than 10,000 nautical miles sailed in 76 days saw her arrive in New York on 29th August.

Discharging bagged sugar and loading a complicated general cargo, would entail a long stay in port, a period of time that Captain Mellis appears to have taken advantage of. On 25th September he married Jessie Anne Innes of Lossiemouth at 449, 6th Street Brooklyn, the house of Mr. John Munro. The ceremony was presided over by the Rev. Hugh Maguire and no doubt suitable celebrations ensued. The Captain would be accompanied by his new wife who was the daughter of Captain R. Innes. The Innes family were well known seafarers in north east Scotland and Captain Mellis and Jessie, the sister of the Mate James Innes, may well have had a long standing relationship. Leaving New York on 3rd October for Brisbane, a voyage of 15,000 nautical miles and taking 114 days, Jessie had plenty of time to adjust to her new life.

Trading 1892.

After a long passage the vessel arrived in Brisbane on 25th January. It may be of interest to note the contents of the general cargo consisting of:

12,000 cases of `Tigar oil`, 500 cases `Light of age oil`, 150 cases of turpentine, 5 cases fish, 110 cases grease, 50 case meats, 100 cases axes, 100 barrels resin, 10 cases books, 20 cases glasswear, 6 cases varnish, 2 cases organs, 205 cases lube oil, 14 cases kalsomine, 2 barrels glucose, 220 boxes soap, 3 packages clocks, 5 cases nails, 50 cases carriage wheels, 50 cases turpentine, 115 cases canned meats, 10 bundles oars, ? reels wire, 6 cases dental goods, 100 cases gasoline, 45 packages of carriage ware, 7 cases castings, 28 packages carriage ware, 20 cases concertina, and sundries.

This general cargo contained a number of volatile substances particularly when carried in cases which were prone to leakage, any fire would have meant the vessel`s destruction. Completing discharge she sailed for Newcastle New South Wales in ballast (no cargo) on the 8th February to load 747 tons of coal for Mauritius.

Loading completed she departed Newcastle on 14th March and Captain Mellis decided on a track north about Australia, outside the barrier reef and through the Torres Strait. This avoided the prevailing westerly winds to the south of Australia and made use of more advantageous conditions for the passage. On 21st April she was reported passing Goode Island in the Torres Strait.

That report was the last news of the ship. About the estimated time of her arrival a violent typhoon struck Mauritius and in June of that year a lifebuoy from the ship was found on the outer reefs of the island. By then she had been posted as missing in Lloyds described in one simple line:

“Passed Goode Island,Torres Strait, on 21 April,1892, and not heard of since”.

There were no survivors, the presumption being that the vessel foundered in the typhoon off Mauritius. She had sailed over 100,000 nautical miles in 3 years under the same Master.

Epilogue

The sad loss was of course reported in the Scottish press and the `Elgin, and Morayshire Advertiser` in September 1893 contained the obituary of Mr. Robert Innes Shipmaster, and father of Jessie Anne and James.

“He never seemed to recover from the fearful blow occasioned by the loss of his son Captain James Innes, his daughter and son in law Captain T. Mellis.”

James Innes was Bosun in the vessel in 1889 and must have gained a Certificate of Competency for by 1891 he was mate of the Osman Pacha at the time of her loss.

This narrative reflects the trading and details of an ordinary foreign-going sailing vessel of the late 19th century. There was nothing special about the Osman Pacha, indeed a similar Shoreham ship, The Britannia, built one year before the Osman Pacha at the same yard, suffered a similarly tragic fate. She struck Sable Island, 85 miles south east of Nova Scotia, in September 1883. Captain Gasston survived but lost his wife, two children and all the crew save three souls. Innumerable ships foundered or were wrecked during the 19th century and many local tragedies were documented in The Ships and Mariners of Shoreham. Having only sextant, log and magnetic compass for navigation an accurate position was often difficult to obtain in bad weather when sailing vessels were at the mercy of wind, fog and sea.

An estimated 200,000 + seamen were active in the latter half of the 19th century, and an average of 3,000 a year were lost to drowning and accidents. Over 2,000 were also lost to disease, giving a mortality rate of 23 per 1,000. These figures are 18 times the mortality rate suffered 100 years later. Men were sick by the age of 40 due to the conditions and poor food. Scurvy was still met in merchant ships and indeed increased in the 1880`s. It was a hard younger mans` life and the conditions only slowly improved into the 20th century as new safety legislation and safer steam ships effected service conditions. A romantic calling it was not.

The correspondent for ”The Elgin Courant and Morayshire Advertiser” eloquently expressed the feelings of many bereaved families

“The sea demands a heavy penalty for ploughing its waters, and this penalty is well known in the innumerable scars left on the hearts and vacant homes of the British sailor.”

TIME LINE 1878.

1878. Launch and lay up Shoreham.

1880. To London Dry Dock and Lay up West India Dock until.

1888. December Dry Dock.

1889. January- Load first cargo- sail 27thFebruary to South Africa.

24th June. Arrive – discharge – sail to Maritius in July to load for New York.

21st October. Arrive N.Y. – discharge – load – 13th November sail for Capetown.

1890. Capetown – discharge – sail to Mauritius–load for Melbourne 29th April.

3rd June Arrive Melbourne – Discharge sugar- load coal.

29th June sail for Port Augusta.

14th July.Arrive Port Augusta-Discharge coal- load wheat.

5th August sail for Port Elizabeth arrive 30th September. Discharge – sail for Mauritius

13th November Arrive Mautirius- load.

6th December – sail for Karachi

1891. 16th January arrive Karachi

27th January sail for Chittagong – 13th March arrive

26th March depart for Mauritius – arrive May.

14th June depart for New York.

29th August arrive New York- discharge- load- marry.

3rd October depart for Brisbane .

1892. 26th January Arrive – discharge general cargo- sail for Newcastle. 14th March complete loading coal- sail for Mauritius-21st April vessel reported in the Torres Strait. No further sighting.

POSTSCRIPT

An Indian Ocean Typhoon was not to be underestimated.

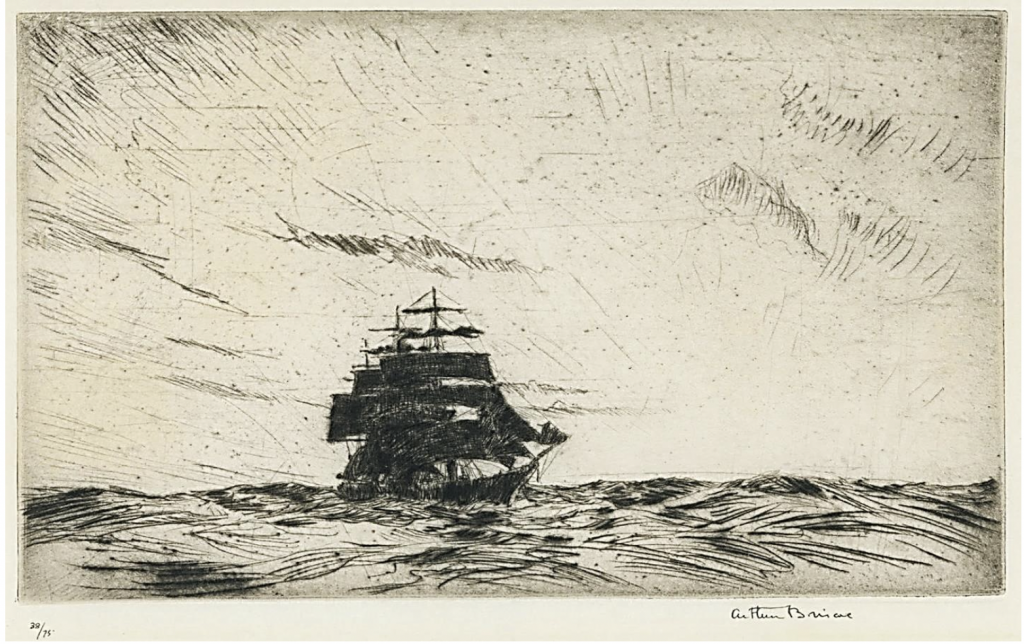

Alastor (Courtesy of the Marlipins Museum).

The partially dismasted Shoreham owned iron barque Alastor lying to two anchors off Port Louis, Mauritius. Damaged by a severe Typhoon she sought shelter for repairs some 10 years before the loss of the Osman Pacha. Built by Mounsey and Foster of Sunderland, she was owned and managed by R.H. Penney for 24 other Quakers. The largest sailing vessel in his fleet she was sold to Norwegian interests in 1895 and survived into 1950`s. She mainly traded to New Zealand with general cargo and emigrants.

Appendix 1 a

Articles of Agreement 1889

Appendix 1b

Crew List

Appendix 1c

Crew Pay and Allotments with addresses 1889.

Appendix 2

Crew list 1891

Sources:

British Newspaper Archive.

Cheal. H. Ships and Mariners of Shoreham.

E. Goodchild. Will and Probate.

Hope. R. A New History of British Shipping. (London 1990 )

Lloyds Registers 1888- 1892.

Lloyds survey certificate 1880.

Lloyds Lists 1888-1892.

Maritime History Archive. Memorial University, Newfoundland

Crew Agreements 1889 and 1891.

Sussex Archeolgical Society: Marlipins Museum Shoreham.

Pudney. J. London`s Docks. (Thames and Hudson 1975)

State Library of South Australia. slsa.gov.au

`Trove` on line Australian papers. trove.nla.gov.au

Wales online.co.uk