-the Tillstone and English families

“…… the shouts of the workers, the creak of the rope and winches, the ringing of the signal bells and the pervading smell of tar must have left a strong impression on the senses.”

Rope and sail making has been an important part of Shoreham’s shipbuilding industry for hundreds of years but it is only during the 18th and 19th centuries that we know more of the men and their families involved.

Many Shoreham families were employed in these trades including those of Parsons, Phillips and Rowe but the two most prominent at this time were the Tillstones and Englishes. The first entries for Tillstones in the parish records are in the 1740’s which suggests that originally four of them settled in Shoreham during the early 1700’s, probably attracted by the opportunity for rope and sail making work in the town’s ship building industry. Perhaps they were brothers although one of them, Nicholas Tillstone, may have been the patriarch and he does not appear to have remained in Shoreham much after 1780.

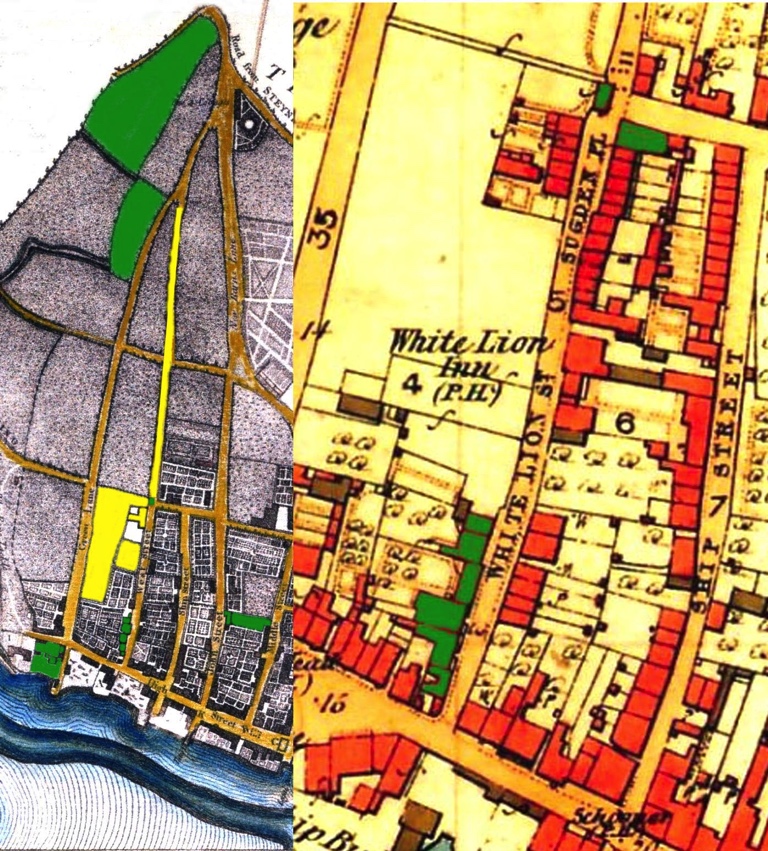

The 1782 Survey shows Nicholas as owning a house (today’s number 5, West Street) which remained in the family’s ownership into the 1870’s. This and other family property was partly passed on to Michael and Thomas Tillstone but primarily to Richard Tillstone then on to Richard’s sons Benjamin and Joseph as later beneficiaries.

Further up West Street was once a rope winding house that they also owned which had originally been built in the middle of the thoroughfare by a man named Piercey and was, the surveyors reported, “on waste for which a grant was never obtained from the Lord.” Presumably permission was eventually secured from the Duke of Norfolk (who owned the copyhold) as the winding house continued to be used for many years after, twisting the ropes all the way up the ropewalk to where it meets the top of Victoria Road. It was still appearing in the street maps of the 1870’s.

Other property that the family possessed included no’s 30 & 32 John Street (the building with the right-angled, protruding front room that legend holds was a smuggler’s look-out) where Richard Tillstone lived. They also had Little Dam Field (now 45 to 77 Victoria Road) and the field above it to the west (now Overmead) perhaps used for drying newly tarred sails – the latter was previously owned by the Bartlett family that intermarried with the Tillstones and the long flint wall backing on to the Little Dam Field built by Thomas Tillstone still has a stone tablet set into it inscribed ‘TT 1835.’

Another property of note was the land on Ropetackle (where ropes were made in ancient times) immediately to the west of where the road bridge now meets the High Street. At that time (1782) the cottage on it was occupied by John Sawyer but the remainder of the site which included more premises, a warehouse and a shipbuilding yard was where the Tillstones also built ships. Benjamin Tillstone owned this part of the family land which with his other business as a brandy merchant enabled him to lease a large house in West Street and the field behind it called Bayfield which then included a windmill, all owned at that time by the ancient Fawler family of Shoreham (by 1860 the house had been replaced by today’s four houses numbered 49 – 55). Obviously a shrewd business man he later became wealthy enough to rebuild Moulsecombe Place at Brighton.

From 1810 to 1816, first Thomas then Benjamin were also owners of the King’s Head inn and the land behind it – this and Thomas’ land behind his house in John Street were used by the army as a camp to accommodate troops as part of the coastal defences during the Napoleonic Wars when fear of invasion was rife.

In the meantime the bread and butter business of the Tillstones was the rope and sail making business which was ably carried on by one of Richard’s other sons Joseph. He in turn sired another Joseph and between them continued the considerably successful business that had become so well known nationally. The Parish Poor Rates of 1833 discloses a somewhat lesser amount of property held than fifty years before but nevertheless Joseph Tillstone senior and junior possessed between them a continuous row of half a dozen houses in West Street that included number 5, stables, two fields, a warehouse, tar house and ropewalk.

The late 18th century records imply that the family actually owned the ropewalk at one time but perhaps they were simply granted the use of it. Whether or not this was to the exclusion of all other townsfolk is not known but with five or more ropes stretched out alongside each other there would not have been much room for pedestrians and certainly not horse drawn vehicles.

The flint faced barn or warehouse on the corner of West and North streets is believed to have been built by the Tillstones and was probably used for a number of purposes including a sail loft but certainly incorporated the tar house – we know this because by the 1880’s James W. Patching (he ran the ironmongers shop in the High Street) is recorded as using a “tar house late Tillstone’s” in West Street to stable his horses and continued to do so well into the 20th century. The north side of the building still has the small apertures (now windows) and it is tempting to assume these were also used for playing out ropes up the ropewalk but the barn was not built until after 1812 and there were then two buildings opposite to prevent passing the ropes through to the walk. The near end still sports the projecting beam used for lifting bales by pulley and the original doorway on the ground floor can be made out around the modern window.

The manufacture of rope was both skilled and complex involving many different tools and processes and only a brief description is offered here. In the early years the Tillstones may have purchased the basic hemp fibres in bales which were then spun on spinning wheels to produce the yarn for the basis of the ropes – by the 19th century if not earlier, ready spun yarn was also purchased in reels.

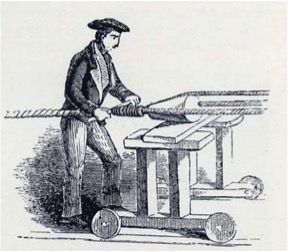

It would be passed through hot tar which had to be maintained at a very high temperature and at the right pace to enable the fibres enough time to soak up the liquid tar (“preferably Archangel tar mixed with a little Stockholm which should be of a bright colour when rubbed between the fingers” – how did you do that without scalding them?) after which the yarn would be coiled into ‘hauls’ then left for several days to dry. Each end of a sufficient number of yarns according to the thickness of the strand required was then fixed on the hooks of a wooden frame and the other ends threaded through holes in the metal disc of a winding machine and passed through a tube of a gauge equivalent to the total of the compressed yarns. The yarn was then made taught and drawn down the ropewalk and twisted as it was paid out – this created the thicker strands, the tension and amount of twists being carefully checked during the whole process.

The final stages involved fixing the ends of the strands required for the rope to a ‘jack’ – often just a basic frame with simultaneously revolving hooks that were turned by hand from a large wheel. The other ends of the strands were all fixed to a freely rotating single hook on a weighted trolley called a ‘traveller.’ To support the rope stake heads would be driven into the ground every 5 fathoms (nautical measurements used by rope makers – one fathom is six feet in length). With the jack at one end of the ropewalk and the traveller at the other the operators on the jack and traveller would signal each other by using handbells to start the twisting from the jack end which tightened the strands – when it was taught enough the jack would be stopped and the winding commenced from the traveller instead. As the rope hardened and tightened the traveller slowly moved along the ropewalk until the tension and gauge were considered sufficient. Ropes made this way were known as ‘hawser laid’ and those made up of three hawser laid ropes were called ‘cable laid’ rope – hence hawsers and cables.

All this endeavour would have made the top of West Street an active part of the town with men, women and children (there is a record made in the 1870’s showing a payment of 6d to a child for a morning’s work on the winding swivel at the ropewalk) spinning, twisting and proofing with boiling tar prepared in the tar house and the sail makers cutting, sewing and tarring canvas. There would have been a number of different thicknesses of rope stretching from the winding house and winches alongside, up to the top of the ropewalk where there were similar winches or capstans – for anyone working there or walking by, the shouts of the workers, the creak of the rope and winches, the ringing of the signal bells and the pervading smell of tar must have left a strong impression on the senses.

Following the death of her husband in 1844, Joseph junior’s wife Susannah continued to enjoy the income from the business as well as the rent from the West Street houses including the ‘Builder’s Arms’ pub that was now being run from number 5. Susannah lived on until her demise in the 1870’s in one of these houses with her daughter, also Susannah. In fact she is shown in the 1851 records as a ‘former rope maker’ so was likely to have been involved ‘hands on’ in some of the processes herself. This practical knowledge doubtless enabled her to continue to be much involved in the running of the business. Among the men she employed were William Woolgar English, a rope maker and later his two sons – William junior and Thomas.

Thomas English’s grandfather Edmund had long been the landlord of the Crown and Anchor in the High Street. Edmund’s eldest son, William Woolgar English b.1841, became a coal merchant and rope maker and already had an association with the Tillstones through his work – in his later years he followed his father to become landlord of the Crown & Anchor as well and it is this family that ran the famous English’s Oyster Bar in Brighton. Of William’s two eldest sons William junior (b.1841) was a sail maker and Thomas (b.1843) a rope maker like his father. Working for the Tillstones would have brought Thomas in contact with Susannah’s daughter and it seems they took a shine to each other for in 1865 they married and in so doing Thomas inherited the business through his wife.

The construction across the ropewalk of the bank for the new railway line to Worthing in 1846 may have interrupted work on the manufacture of ropes but only temporarily. As soon as the West Street bridge was finished the ropes were thread through it and once again work continued for another 30 – 40 years. However, very gradually demand was beginning to wane following the decline of the ship building industry and during the 1880’s rope making in Shoreham ceased altogether which was probably the reason why Thomas, Susannah and their family moved then to Yately in Hampshire to take up dairy farming. It seems however that there was still sufficient business, if not for rope making then for sail making and the census returns continue to show various members of the English family including Thomas’ brother William junior (then still living at number 11 West Street, one of the old Tillstone houses) working that trade into the 1890’s.

Census returns disclose that there were around nine rope makers in Shoreham in any one year up to 1881 but none thereafter. Despite the collapse of ship building however, emerging yacht making firms such as Thomas Stow and Sons, then Suters and others continued to flourish for many years after, enough to provide work for eight sail makers in 1891 and beyond but by then most of the English family had left Shoreham and those that remained were no longer involved in the industry.

Roger Bateman

Shoreham July 2010

Reference Sources:-

1782 Survey of New Shoreham

New and Old Shoreham Parish Records

New Shoreham Land Tax Returns

New Shoreham Parish Poor Rates

New Shoreham Census Returns

Property Deeds for 5 West Street

‘A Bibliography of Cordage and Cordage Making’ by Robert Chapman 1868

‘Felbridge Rope Walk’ – Felbridge District History Group 2009

‘The Story of Shoreham’ by Henry Cheal 1921

‘A Walkabout Guide to Shoreham’ by Michael Norman 1984

Rope Spinning Loft photo of Plymouth Cordage Company Ropewalk at Mystic Seaport

~ http://www.mysticseaport.org courtesy of Mystic Seaport, Mystic, Conn.

As a new resident at Marline Court, Ropetackle, I found this very interesting.

An old friend who used to live in Shoreham, by the name of Parsons, had a marquee making and hire business last based in Eastern Road in Brighton (on the site now occupied by Gala Bingo). Do you know if there is any connection between them and the Parsons Ropemakers in Shoreham?

Thank you.

It doesn’t seem as if anyone knows Paul. It looks like your only option is to identify one of the last rope maker Parsons in Shoreham then trace that forward using the Free Birth Marriages and Deaths website, Census Returns etc., but it’s not an easy job.

I have a newspaper bygones picture from the shoreham herald ( year unknown) showing the sail loft and subsequent letters to the paper identifying the people shown from my grandfather J R English and his family. When the sail making declined they made tarpaulins to sell around the farms and I believe marquees.